Joel Leonard is afraid he may be coming down with a cold. As we walk along Copenhagen’s lakeshore, the February winds have caused his nose to run. His adopted city, Joel has written, smells to him of “Baltic salt, cold mud, broken reeds on the lakes’ surfaces, and damp woolen coats.” Removing a black leather glove, he reaches into his coat pocket and pulls out a handkerchief, which he presses gently to each nostril. Joel, who is sixty-two, hasn’t blown his nose since he was four years old. “It ruins my sense of smell,” he told me once, his native Bronx accent untamed by forty years in Denmark.

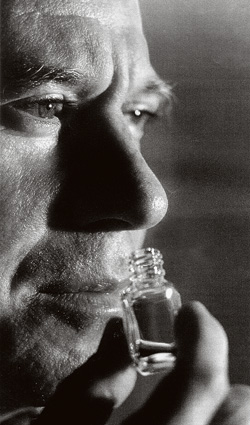

Joel’s nose is bulbous and robust, webbed with broken capillaries like a road map of some seldom-traveled region. The fragility of his nose is just one of the many challenges Joel faces in founding his livelihood on something as transient as smell: it demands abstemiousness. Joel has to avoid not only nose-blowing but also steam baths and hard liquor, two staples of the Scandinavian lifestyle, particularly during the dark and frigid winters.

We’re headed to a yoga center where this afternoon Joel will be leading a scent-meditation session. A light snow has begun to fall, speckling the shoulders of his black cashmere coat and the mustard-brown shawl he’s thrown around his neck. Joel is short and a bit paunchy with a leonine froth of white hair. White tufts of eyebrows wilt over his eyes, and a permanent flock of furrows rises into his forehead, giving him an expression at once bewildered and hopeful.

Joel is a fragrance designer and scent-meditation teacher. He runs his business out of his one-bedroom apartment, where he lives alone. He has no employees; he has never found anyone with a kindred sense of smell. Companies come to Joel when they want to infuse scent into a product they’re trying to market, or create a suggestive aroma for a public space. In his scent-meditation sessions, Joel burns incense and anoints participants’ foreheads and wrists with a series of fragrant oils, whose scents progress from subtle to intense. He has found that when his clients experience their own odors and breath merging into the shared aroma of the room, their individual boundaries dissolve into a kind of olfactory communion. Joel also teaches koh-do, an esoteric Japanese scent-meditation game akin to the tea ceremony. What ties these pursuits together is Joel’s belief in fragrance as a form of nonverbal communication that can liberate us from ourselves and connect us to each other. He draws on ancient traditions—Sufism, gnosticism, Aztec religion, and particularly Buddhism—that have used scent as a means of communication between the individual and a higher realm, and translates these concepts for the modern world.

In his book Perfume: Joy, Scandal, Sin, professor Richard Stamelman describes perfume as “a fable about the impermanence of life,” “the essence of absence.” In Joel’s world, smell is about the present moment, and it’s possible to smell with a sort of nonattached attachment. “If I smell a flower, first it’s a floral scent, then it’s a rose, then it’s a rose in rainy weather, then it’s a rose in rainy weather with the sun going down, then it reminds me of smelling a rose in a garden by the sea as a child. I think, Wait! I’ve got it! And then it changes into something else.”

From a commercial standpoint, the increasingly popular use of custom aromas to market otherwise unscented products and to mask odors or create ambience in our cars, offices, and homes (the latter is a $4.4 billion industry) has dovetailed conveniently with Joel’s work as a fragrance designer. He has found ways to infuse fragrance into cleaning fluids, felt furniture pads, air-conditioning systems, and textiles. Two years ago the managers of a Scandinavian restaurant in Copenhagen asked Joel to create Nordic scents for their dining room to enhance the cuisine. Joel traveled around Scandinavia collecting scent memories of pine forests, fjords, and coastal ports. He re-created these scents and worked them into the restaurant’s wood polish, table linens, and waiters’ uniforms. Bang & Olufsen asked him to design a trio of scents for the plastic in phone receivers meant to appeal to three different types of female consumers: the young mother, the “career girl,” and the middle-aged housewife. The authors of a psychological coaching book enlisted him to create an aroma for the books’ spines that would stimulate readers’ memory of the material. And a Danish society for the blind hired him to invent a “scent language” to help its students communicate their needs (Joel created vials of smells representing twenty-five basic words that could be used in combination: pizza + car = go out for pizza). Currently, he’s developing meditative scents for the chapel in Copenhagen International Airport. “It’s like storytelling with fragrance,” Joel says of his work, “using mnemonic devices to communicate nonverbally a history or a feeling.”

In today’s culture of materialism and instant gratification, however, it can be a challenge to convince people that something as ephemeral as smell can transform a space or facilitate serenity. Joel works only with natural scents. Synthetic fragrances, which are created in labs from man-made molecules, are the mainstay of the commercial fragrance industry. Because they are not derived from raw materials, synthetics are less expensive to produce and often last longer, making them a more economical option for large-scale projects. Synthetics, however, lack the complexity and richness of natural scents, much as the sound of a synthesized cello can’t compete with the resonance of the stringed instrument. It isn’t Joel’s mission to abolish synthetic fragrances. But he has witnessed a growing market for his services and a growing interest in his belief in “experiencing scent at the physical, mental, and spiritual levels.”

Hansa Yoga Center, where Joel will hold today’s meditation, is a low-slung gray building off an alleyway in northern Copenhagen. Inside, winter light washes across the bare white walls and floorboards, bathing the room in stillness. Simon, a long-limbed yoga instructor with keen eyes and a shaved head, is lighting tea lights in the windows. As today’s session was arranged at the last minute, he and I will be the only participants.

“Do you want me to air out the studio for you, Joel?” Simon calls from across the room.

“There is a sort of rosy smell in here, isn’t there?” Joel sniffs. “Maybe it’s the geranium.” There’s a pink geranium in a clay pot on the windowsill. Joel walks over to the plant and considers it. Rather than exiling it, he carries the geranium across the room and sets it beside his “travel altar,” which he has unpacked from a black plastic attaché case (along with—sheepishly—a copy of Eurowoman magazine). Now, sitting cross-legged in a dark wool sweater and pants, a white cotton shawl draped over his shoulders, Joel looks every bit the fragrance guru. Until he speaks, it’s hard to remember that he grew up in the Bronx.

“Close your eyes,” he says. He tells us to concentrate first on our own odor. I inhale and smell complimentary hotel shampoo and the sweat trapped in my sweater from when I ran to catch my flight three days ago. I start to worry that Simon can smell me. I open one eye and peek at him, but he’s sitting like a yogi. (On the last day of my visit with Joel, I asked him the question anyone would be wondering after spending ten hours a day with a master nose: what do I smell like? Joel blushed, then responded: “You smell like you’re growing.” I was surprised, embarrassed, and unexpectedly moved; Joel had told me he could smell emotions and illness, but he’d never told me he could smell change.)

There’s the flick-rasp of a lighter, and smoke from a beeswax candle infused with incense curls into my nostrils. All of Joel’s scents include agarwood—his signature fragrance, and one of the rarest raw materials on the planet. I try to stop thinking about my smelly sweater and let the smoke take me out of myself into the room. Joel places a small piece of agarwood in our hands. It is dry and light. I let the warmth of my palms release the fragrance. The scent reminds me of wood smoke, maple, mothballs. I begin to draw deeper breaths, and for a few moments I’m transported to a cabin in the woods. His fingertips press cool oil onto my wrist and forehead; it has the smoky sworl of whiskey. Warmth descends through my body and I exhale it into the room. I imagine the smell of my scalp mingling with the smell of Simon’s rag-wool socks. It’s like there’s a ribbon of scent weaving from the altar, through me, through Simon, and returning again. It occurs to me that Joel’s theory of scent communion is not unlike being stuck in an elevator with a group of heavy breathers, only the smells are rare incenses rather than cologne and Quiznos subs.

The room is silent except for the susurrations of the candle and a distant plinking of melted snow dripping into a gutter. We continue inhaling and exhaling, using an adaptation of the alternating nostril technique of yogic pranayama breath. Joel seems bodiless now, the only evidence of his presence the rattle of his mala beads washing against each other.

Some traditionalists might frown on Joel’s scent meditation sessions as an appropriation rather than an incorporation of ancient rites. As UC Berkeley professor Robert Sharf explains, most Asian Buddhists view incense as an offering to something outside of the self—to a buddha, bodhisattva, or protector deity. Offerings of incense, like offerings of food, flowers, and other objects, are seen as expressions of respect to a higher being and as a means to cultivate good karma. Joel’s use of incense to facilitate communion strikes me as more of an internal offering, even as meditators lose themselves in the mingled fragrances of the meditation room: the practice is less reverential than self-centering. Still, as Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara of New York’s Village Zendo points out, “Incense is always a reminder of the transience of the solid thing changing to emptiness,” a notion that forms the core of Joel’s philosophy. She also notes that because of the potency of our smell memory, the familiar scent of incense at the start of a meditation serves as a reminder to practitioners that it’s time to clear the mind, which certainly plays a role in Joel’s sessions.

He had told me he could smell emotions and illness, but he’d never told me he could smell change.

When we open our eyes, it is snowing. Simon wiggles his toes. We smile hesitantly. I feel a flush of shyness, as if I were facing someone the morning after an intimate confession. A ring of heat pulses the final feathers of smoke from the incense stick. I feel as though I have a safe, warm space inside me in this bare room with the tea lights and the snowflakes fluttering past outside. Joel rises from his cushion and bends down to lift the geranium from the altar. Wordlessly, he returns the plant to the windowsill.

Joel first discovered he had an unusual nose at age four, in his backyard in the Bronx, during a game of Blind Man’s Bluff. He realized that even when blindfolded he could identify his friends by their smell. “People would run by me and I’d call out their names and they said, ‘You’re cheating,’ you know, ‘only a dog can smell people.’ I was very unhappy. I came home and I said to my grandmother, ‘The kids don’t understand that I can smell who they are.’” His grandmother told him he’d inherited a family gift. “She told me that I had to be very careful with my nose, that this would be my tool in life.”

It’s dusk, and we’re sitting in a café overlooking Copenhagen Harbor. As Joel talks about his rather apocryphal-sounding past, he occasionally shrugs and shakes his head, as if he can’t quite believe it himself.

Joel’s education began in his grandmother’s kitchen, where she trained him with cups of kitchen spices. In high school, during a year abroad in Mexico, his host mother taught him how to make his own plant-based scents. He studied anthropology and pre-med at the University of Chicago and Columbia, spent a year in Jerusalem studying biblical archaeology and fragrance, and two years at medical school in Grenoble studying rhinology. In 1967 he found himself in Copenhagen, where he met and fell in love with the Danish woman who would later become his wife (they are now divorced) and the mother of his three children, now in their thirties. The couple settled in Copenhagen, where he’s lived ever since. At the mention of his family, Joel pauses and turns to the window, where a fishing boat is slipping by against the darkening skyline. His eldest daughter and two young grandsons live in Thailand. For all Joel’s talk of nonverbal communication, there are some distances even incense smoke can’t bridge. (He once wrote me: “Pardon the bragging grandfather, please, but my eldest grandson told me he only plays with kids ‘who smell right.’”)

Joel had already begun a career as a fragrance importer when one day, in 1988, he got his first whiff of agarwood. A friend had mentioned that a Zen master was coming to Copenhagen to conduct a koh-do ceremony, and Joel decided to attend. When the Zen master lit a piece of agarwood and passed it around the room, Joel says, “I felt that I knew this fragrance from somewhere, and I had to know why it was so appealing to me.”

Agarwood (also known as aloeswood) is the most valuable wood in the world. Its fragrance has consistently eluded synthetic imitation. The scent derives from an aromatic resin that the Aquilaria tree, a flowering evergreen from southeast Asia, produces as an immune response to a fungal infection. Attempts have been made to wound the trees to make them more susceptible to the infection, but the fungus is so rare and the scented wood so valuable that agarwood farms have been prey to poachers. Joel once showed me photographs of a farm he had visited, surrounded by barbed-wire fences and machine gun-wielding guards.

Though Joel now has his own collection of agarwood, he brought me to see a three-hundred-year-old piece in the Japanese fragrance collection of Copenhagen’s National Museum, a room he was commissioned to design and which he oversees. The museum piece, about the size of a small cat, is enormous by agarwood standards. The gnarled wood grain resembles a turbulent river frozen in midstream.

After that first koh-do ceremony, Joel found himself haunted by his memory of the smell of agarwood. “Every night for about two months, I dreamt dreams with this fragrance,” he tells me. He wrote to Shoyeido, the incense company that had sponsored the ceremony, requesting a visit, but received only rebuffs. Four years later, at the age of forty-eight, Joel obtained a study grant and made his way to Japan. He had in his pocket the address of the Zen master who had conducted the service. “I got on a train and went to his house, a humble abode in a quiet part of Kyoto, and I knocked on the door,” Joel says, “and he opens it, and he says, ‘Where have you been? We have no time to waste!’” Although Joel had attended his koh-do session, the two had never been introduced.

Kawata Bayashi, who was eighty-four at the time, spent the next few hours racing up and down the stairs, throwing books from the shelves, trying to impart as much knowledge as possible to his long-awaited disciple. Later that afternoon, he dropped Joel off at a temple where an incense meditation was taking place. Joel introduced himself to the other participants and described his unexpected reception from Bayashi. “They all looked at me incredulously and said, ‘We can’t believe what you’re saying. Kawata Bayashi is practically blind!’” When I ask how Joel accounts for this, he throws up his hands and chalks it up to the power of nonverbal communication.

So began Joel’s induction into the world of incense. With Bayashi’s sponsorship, Joel became an apprentice at Shoyeido, commuting between Copenhagen and Kyoto, learning the fundamentals of Buddhism and incense craft. He spent his mornings meditating in a secluded garden, trying to capture the smell of “mist rising from a garden at dawn” for one of the first incenses he was asked to create. “My experience in Japan led to a kind of spiritual awakening for me, where teachings from different Buddhist schools have been integrated in my own meditation form,” he says.

In 2002, Joel visited a mountaintop village in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta whose inhabitants cultivate agarwood and practice an esoteric form of Buddhism. “As soon as we come into the village,” he tells me, “there’s this guy, he has like a headdress on, and we make eye contact.” His interpreter told Joel the man was a local priest. “He starts running toward me and he says, ‘The Buddha has brought you to me.’” The parallels to Bayashi were uncanny. The priest told Joel that in the Buddhism his village practiced, agarwood was used as a bridge between the individual and a universal expression of the Buddha. “He told me, ‘I travel on the incense smoke up to the heavens, and when I come there I am met by the spirits. This fragrance is the fragrance of the gods.’ For me this was a breakthrough, and I felt that I was coming back to some kind of collective-conscious knowledge.”

Joel returned to Copenhagen, eager to bring the transcendent benefits of scent to his city. Danes are fond of saying of their country, “There is no one who has too much, and even fewer who have too little.” But according to Joel, who is a Danish citizen and is unabashedly proud of his country’s history, beneath Denmark’s vigilant safety, obedience, and classlessness lies an underbelly of dissatisfaction. “It’s the most unhappy place I’ve ever experienced,” he told me. Joel has felt the shadow side of hygge, or coziness, the Danish concept of shutting out the turmoil of the outside world—which, he says, can sometimes extend to foreigners. Joel is an unmistakable New Yorker here: he speaks fluent Danish, but with a strong Bronx accent, and shuns the proscription against jaywalking, earning him glares at every intersection. “My clients have BMWs, nice houses, but they seek me out because they’re not content on the inside.” When I ask Joel why he’s chosen to stay here, he tells me he views Copenhagen as a microcosm of where the world at large is headed. “Scent is the universal language, which will be able to reach people in this society that is quickly becoming overburdened with information,” he says. Copenhagen provides an endemic challenge to his mission: “to bring joy and relief through fragrance.”

One blustery night, Joel; his son, Mika; and I are seated around the table in Joel’s apartment for an informal koh-do ceremony. Joel learned koh-do—“the Japanese way of fragrance”—during his tenure in Japan, and he periodically hosts koh-do games as an alternate form of scent meditation. Mika, 33, is an aspiring musician with a soft voice, a shaved head, and delicate hands. Though he is Joel’s closest friend in Copenhagen, and sees his father several times a week, this is his first koh-do session as well.

As soon as Joel opened his front door and ushered me in, the smell of incense wafted across the threshold, mingling with the stale cigarette smoke hovering in the stairwell. The room is furnished with a tapestry-covered couch, a ceiling bulb covered by a rice-paper shade, and low bookshelves bulging with dictionaries. Dozens of flasks, atomizers, and jars holding perfumes, flower petals, and pieces of wood are haphazardly crammed into every available nook, from the living room to the bathroom. The walls are covered in photographs, prints, and souvenirs. Joel serves us bowls of green tea and hard, colorful Japanese rice candies. He’s put on a CD of gamelan music to drown out the drum session taking place in the apartment above. A gooseneck lamp arches over the table where Joel is unpacking his koh-do implements—worth $10,000—from a red cellophane bag that looks like it came from a fruit stand in Chinatown.

In an official koh-do game, the “master” selects incenses to represent verses of a seasonal poem or story. The first verse might represent “evening mist settling on cherry blossoms,” the second, “lady standing on a bridge,” a third, “sound of a distant flute.” In a series of ritualized gestures, the master circulates a censer of each fragrance among the participants, who are each given three inhalations to commit the aroma and its verse to memory. In the final round, the master selects one of the incenses at random and passes it around. The “winner” is the person who correctly identifies the fragrance. Given the game’s meditative element, however, koh-do is less a competition than a collective invocation of time and place through the commingling of incense and poetry.

“Scent is the universal language, which will be able to reach people in this society that is quickly becoming overburdened with information.”

But since Joel hadn’t applied to his master in Japan for permission to host this evening’s game, and as Mika and I are the only attendees, he emphasizes that it will be more of a “demonstration.” To select a poem, he wrests a Wordsworth volume from the bookshelf and paces the room in his socks, flipping through the pages, his white hair corralled into a nubbin at the base of his neck. Finally he settles on a verse from “Intimations of Immortality” and reads it aloud in his incongruous accent: “O joy! that in our embers / Is something that doth live, / That nature yet remembers / What was so fugitive.” “Joy, embers, nature,” Joel murmurs, snatching some paper and a pencil stub from the desk and scrawling down the words and his ideas for matching scents. Though the poem doesn’t evoke a season or a story as traditional koh-do verses would have done, Wordsworth’s celebration of nonattached attachment seems appropriate.

Joel lights the first chip of incense and raises the censer to his nose. As he inhales, his slight paunch recedes beneath his thin sweater. His nostrils don’t move. His eyes angle off to the side, and his lips form a thin, serious line. He tilts his head. I have seen Joel at other times draw the object he’s smelling toward his nose, thrust it away, then pull it toward him again, like a conductor coaxing a slow movement out of an orchestra.

If you ask Joel the correct way to smell, he’ll tell you to sniff in short, quick breaths and focus on the inhalation. Joel is only just beginning to develop his synesthetic vocabulary, under the tutelage of an oenophile friend, and he often looks puzzled when you ask him what something smells like. He’ll respond with anything from “tinge of wet dog” to “the sea and mildew, with an undertone of schwarma” to “like a kiss with big red lips.”

The use of incense in Buddhism and for spiritual communion can be traced to ancient times. As Kiyoko Morita recounts in The Book of Incense, in 595 C.E. a strange piece of wood washed ashore on Awaji Island, near Kobe, in central Japan. The island’s inhabitants tossed the wood into a cooking fire, and were astonished when it released a potent aroma. They presented the piece of wood to the royal court in Nara. Prince Shotoku immediately recognized the fragrance as agarwood, which was burned during the Buddhist rituals that had recently made their way to Japan via the Korean peninsula. Shinto, the indigenous religion of Japan, had begun to incorporate many of the features of mainland Buddhist practice, most notably the use of incense smoke to invoke the Buddha’s presence.

As interest in Buddhism led to increased cultural intercourse between Japan and China, the Japanese learned that the Chinese burned incense for pleasure as well as religious use, and the Heian courtiers began to do the same. They draped their hair over scent pillows at night, and invented incense clocks that used scent rather than sound to mark increments of time. A cultural distinction developed between sonae-koh (burning incense as an offering to the Buddha) and soradaki (nonreligious burning of incense). From the mid-1300s to the late 1500s, Japanese aristocrats began increasingly to use incense in scent contests, and as its popularity filtered down to the common classes, elaborate sets of rules developed to govern its appreciation. It was during this time that koh-do developed.

Significant for Joel has been the Buddhist idea of “listening” to incense. He often cites a Buddhist story in which the bodhisattva Manjushri instructs his fellow bodhisattvas that in the Buddha’s world everything is like fragrant incense, and therefore one can “listen” to incense smoke to hear the Buddha’s words. This idea—along with Joel’s experience in the Mekong village—formed the core of his theory of scent as nonverbal communication. And when it is finally my turn to cup my hand over the top of the incense bowl and stick my nose through the hole in my fingers, it does feel like there’s a sort of music—or at least a vibration—emanating from the incense within.

Joel places the censer by my elbow and pronounces “Joy,” smiling encouragingly. Inside the cup, a chip of agarwood no bigger than a fingernail releases a plume of pearly smoke. I feel his and Mika’s eyes on me as I try to perform the gestures correctly: rotate the bowl, elbows up, inhale, exhale to the right. Holding the smoke in, I summon some mnemonic device for joy. A not unpleasant plastic quality in the incense brings to mind a doll named Christine, which my sister and I had torn in half once during a fight on a family road trip. Hoping I won’t have to tell Joel I’d first thought of plastic when I smelled his sacred agarwood, I repeat to myself: Joy, Christine, joy, Christine. I realize that in my desperation to capture the fragrance, I’ve completely abandoned the communal aspect of the game. I should be seeing visions of embers and joy and nature. Instead, I’ve been transported to the backseat of our Jeep, Christine’s severed head in my hands, cotton stuffing and tears everywhere.

As the censer makes its rounds with nature and embers, I realize that the key to koh-do is really a kind of grace. You have to be able to hold on to the scent enough to remember it, while relinquishing it enough to be able to experience the scents that follow. It’s like competing in equanimity: the transcendence—and the victory—is achieved by being as present as possible for each breath.

In the end, both Mika and I guess the mystery scent incorrectly, but, of course, it doesn’t matter. I feel a little stoned. Joel, however, doesn’t want the party to end. Like someone creeping into the kitchen for a midnight snack, he reaches into the bookshelf behind him and brings out three pieces of rare agarwood, which he lights all at once. “It’s like opening a $150 bottle of champagne!” he cries, waving the smoke toward him.

Sparks fly. I get a second wind. But this time I’m transported not to my childhood, nor to Wordsworth’s, but to this moment: to Joel with his ponytail and his accent, to Mika and his gentle ears, to the upstairs neighbors and the bowl of cooling tea by my elbow and the table streaked with incense crumblings, the single bed glimpsed through the door of Joel’s bedroom, how his eyes light up when he talks about his grandchildren, his handkerchiefs and his tales of Zen masters and holy mountains, his penchant for jaywalking, for opening doors for ladies, and for bodies of water that carry the smell of the sea. It seems to me that, in the end, our little incense ceremony was very much in the spirit of the Buddhist idea of incense-as-offering. Ours was an offering not to the deities, however, but to something else outside ourselves: the mundane aspects of everyday life that serve as a kind of god or beacon. These are the daily reminders that can center us in the present moment, and that help us to remember the ways in which we are all connected.

The incense fireworks are over. I glance across the table at Joel. He smiles, and I think—but I’m not sure—I see a flicker of wistfulness cross his lips. But then that too is lost in the ghostly sketches still lingering in the air.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.