DARKNESS CLIMBS THE WILD SAGEBRUSH SLOPES around the Metta Forest Monastery northeast of San Diego. Coyotes bark. In a leveled clearing, light spills out from a simple wooden shrine. Inside all is quiet except for a single voice—pausing . . . going on, pausing . . . going on again.

In clear and certain tones, the voice of Thanissaro Bhikkhu leads a guided meditation for a handful of people sitting Thai-style on their ankles under the gaze of a huge golden Buddha. There are three young men from the outskirts of Los Angeles, a lone schoolteacher from Alaska, a Thai family, and several women and men.

“We look for true happiness and think about where true happiness would be found. Breath anchors us in the present, but even there we find there is change, so we have to dig deeper. The breath and one’s inner happiness are the only real things to rely on. Why wouldn’t you want something you can rely on to be happy? So think about the breath—how the breath is shallow or deep, fast or slow—and concentrate on getting to know the breath.”

It is the voice of a farmer selling his crop to the shipper next door, smoothly arguing for the quality and ripeness of his produce. It’s a voice that recalls Thoreau. Economy, confidence, simplicity, reason. Indeed, it is Thoreau whom Thanissaro identities as one of his earliest heroes.

Like Thoreau, Thanissaro Bhikkhu has founded a kind of Walden as the Abbot of the Metta Forest Monastery near San Diego, the first and only Thai forest tradition monastery in this country. Just as the utopian movement in America was sparked by the advent of the industrial revolution, the forest tradition of Theravada Buddhism was developed in Thailand around the tum of the century by Ajahn Mun Bhuridatto in reaction to the increasing urbanization of the Buddhist monastic communities there. Forest monks abandoned the heavy social demands of the city and devoted themselves to meditation instead.

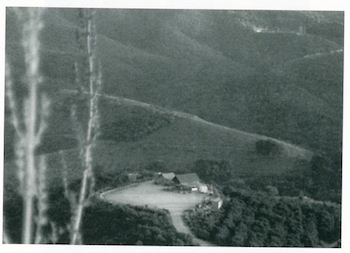

FROM AN ELGHT-LANE FREEWAY the roads grow increasingly narrow. A country road meanders through orchards heavy with lemons and oranges, then turns to dirt and climbs into a mountainous landscape of native chaparral thick with wild rosemary and sage. There is something rough in the dusty air, a whiff of something wild from the Mojave that stretches out over the next ridge.

At the entrance to the Metta Forest, there is no gate, no fence. Nor is there really a forest at all, but a lush 40-acre orchard of avocado trees. From the sunstruck clearing where the monastery’s temple building stands, there is a dazzling view, framed by young palm trees and scarlet blooms of proteus. On a ridge off in the distance the white finger of the Mount Palomar telescope points its lens to infinity.

The handful of buildings are built for an outdoor life. Raised platforms for meditation line the outside edges. There are outdoor sinks and kitchens, broad swatches of white rice drying in the sun. Orchard workers in wide straw hats move hoses around, and here and there are the temporary piles of things that signal a work in progress.

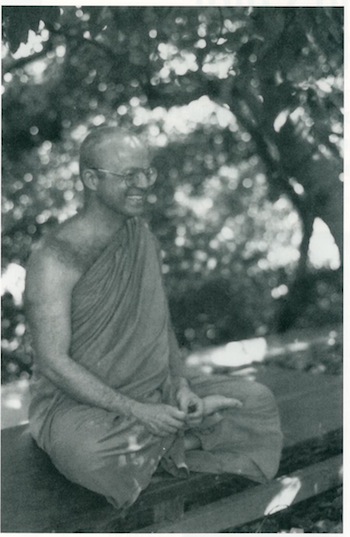

Thanissaro’s robes are the color of the dirt road. His body is lean and relaxed. As we talk at the long table under the overhanging roof, he explains the orchard, sounding like a farmer: “Sometimes the avocados pay us, and sometimes we pay for them. But they are good trees for meditating under; their shade is thick and it’s always cool underneath.”

As we begin to talk a car pulls up and a large Thai family gets out. They shout greetings to Thanissaro in Thai. “We’re on the pilgrimage route,” he explains.” The local Thai people visit us on family outings, but most come from the John Wayne Dharma Study Group in Ontario [California].” The growing Thai community in the area—professionals, doctors, and bankers—have come to the spreading suburbs around Riverside, California, but the land for Metta Forest was donated by a wealthy patron from Massachusetts in 1991 under the condition that the community would find some monks to run it.

Stretched out under a shady trellis on an old Volkswagen back seat, a lanky young man shifts his long bronzed limbs like a local lizard, glancing up periodically to check out the action. The lounging teenager seems an anomaly until Thanissaro mentions that the Buddhist monastic code, or Vinaya, states that a bhikkhu is never to be left alone with a woman; the teenager is our chaperon. The monastic code shapes the setting here as it does all aspects of Thanissaro’s life.

Thanissaro (Geoffrey DeGraff) was born on Long Island, where his father had a potato farm, though later the family moved to Virginia. His father was an elder in the local Presbyterian Church. He remembers the first time he heard the Four Noble Truths. He was in an airplane over the Pacific Ocean flying back from Asia with his fellow exchange students, several of whom had taken temporary monastic vows in Thailand. In his second year at Oberlin College, a special class in Buddhist meditation was offered, and he began meditating with some seriousness. When he had a chance to go to Asia to teach English, he chose Thailand. That was in 1974.

In Thailand, he found his way to the jungle hermitage of Ajahn Fuang Jutiko. Fuang had been a student of Ajahn Lee, a teacher well known in Thailand and a member of the Dhammayut lineage of the forest tradition. When Ajahn Lee died, everyone expected Ajahn Fuang to take over Asoka Monastery in Bangkok; instead, Fuang slipped away as soon as he could to a fledgling monastery in Rayong. Choosing meditation over administration is the forest way.

Thanissaro writes of that time:

Vlat Dhammasathit had the look of a summer camp down on its luck: three monks living in three small huts, a lean-to where they would eat their meals . . . and a small wooden structure on top of the hill—where I stayed—which had a view of the sea off to the south. Yearly fires swept through the area, preventing trees from taking hold, although the area on the mountain above the monastery was covered with a thick malarial forest.

In essence, it was a poorer version of the very place where we are sitting now: a handful of buildings, a few students, a hideout off the beaten track, a forest—of sorts. And after Fuang’s death, Thanissaro also retreated rather than run Wat Dhammasathit, which by now was firmly established. As he explains, ”Ajahn Fuang said to keep moving; this is not a tradition that works well in big groups.”

“When l first saw Ajahn Fuang,” Thanissaro recounts, “he was smoking a cigarette, and I said, ‘Now what kind of a monk smokes cigarettes?’ Bur there was something about him. He seemed very kind and down-to-earth. I had planned on staying three days; instead, I stayed for three weeks, had my visa renewed, and returned for three months until I contracted malaria and had to leave.

“I came back to the U.S. and thought hard about taking vows. I thought of all the professors I knew who were thinking and writing about Buddhism, but l wanted to do it, not just talk about it. Before I met Ajahn Fuang, I thought: If someone spends their life meditating, what are they going to be like? Are they going to be dull and dried up? But Ajahn Fuang was such a lively, interesting person. Finally I decided, I’ll give it five years, and if it doesn’t work I can always come back. That was in 1976. When I said I wanted to be ordained, Ajahn Fuang made me promise either to succeed in the meditation or die in Thailand. There was to be no equivocating. When he said that, it made me certain. I thought, yes, this is what I want.

“In my experience, practicing as a layperson was like looking into a mirror that had a wall of glass blocks in front of it. Living with my teacher was like stripping all the glass blocks away. It was very concentrated one-onone type of study, which is the essential focus of the forest tradition. Fuang had this uncanny way of mentioning something in passing that was exactly what was coming up in my meditation, even before l told him. I sometimes had the sense that we were merely continuing a relationship from a previous life. By the third year I had become Fuang’s attendant and pretty much stayed with him until the end.”

“In part because of his years living in the jungle humidity, Fuang had a terrible case of psoriasis, and how he handled this sickness made me see what a tough person he was. This is a serious disease in its most extreme cases—fever, weakness, the whole thing. Often it would get so bad that he had to lie on banana leaves because cloth would stick to his skin. When he was very sick he would talk very softly with the accent of southeastern Thailand, where he came from. He would ask for something once, and if you didn’t hear him, he would crawl over and get it himself. So you had to be very quick. Also, you had to be very quiet, so as not to wake him. You did it because it had to be done. He wasn’t always pleasant to be around.”

AJAHN FUANG HAD BEEN orphaned early in his life and had taken vows as the only available means of supporting himself. “I have sometimes thought that if he hadn’t become a monk he would have been a gangster,” says Thanissaro. “He had that kind of roughness. As it turns out, one of his best students in Thailand was a former gangster. If you think about it, some of the same skills are required: a sense of subtlety, roughness, independence. In the forest, you are very much thrown back on your own resources.

“In Thailand, a culture where having family and connections is everything, being an orphan has a special stigma. The fact that I was an American in Thailand, without any real connections, meant that I was in essence an orphan, too.” The intimacy of exiles is often the strongest intimacy of all, and the exile spirit is certainly in keeping with the forest tradition. Thanissaro is firm in his conviction that real dharma practice in any culture, to be successful, must be countercultural. Ajahn Fuang wrote: “Our practice is to go against the stream, against the flow. And where are we going? To the source of the stream. That’s the cause side of the practice. The result side is that we can let go and be completely at ease.”

In Thailand, a country where Buddhism is the national religion, complete with “Monk of the Month” magazines and patrons eager to invest stock in the great Merit Market of the monastic universe, countercultural Buddhism has meant, to a large degree, the forest monk tradition.

What countercultural Buddhism means in America (where any Buddhist tradition is arguably already countercultural) may also have something to do with the forest tradition.

In comparison with some other traditions, which in their current efforts to serve an increasingly middle-class following offer attractive weekend seminars at varying prices on popular subjects like “skillful means” or “practice in daily life,” the forest tradition offers absolutely nothing—and charges nothing for it. What it does offer is not exactly quantifiable: knowledge of the breath through meditation; space for, and instruction in, meditation.

When someone comes to the monastery to practice, Thanissaro gives them a basic lesson in breath meditation and shows them to a place under the trees. Scattered through the orchard are a number of simple wooden platforms: one for sitting and a larger one to pitch a tent on. Around each set is a smooth swept path for walking meditation. Mornings and evenings there is a chanting session and a teaching. The subject is usually breath meditation. The simplicity suggested by such a curriculum, in its refusal to be attractive or compelling, is part of the outlaw flavor of Metta Forest.

What students offer in return for the teachings varies: they have brought rice, ice, and bottled water. In a discreet corner of the shrine room behind the giant Thai Buddha there is a book where one may leave monetary donations, but you must ask for it.

The Vinaya prohibition against the use of money extends to not charging those who come to use the monastery, as well as barring Thanissaro from using money. He has traveled through the modern world in yellow robes without a penny in his pocket (nor even having a pocket), and has often waited long hours for rides that were slow in corning.

“In the beginning I was not that enthusiastic about the rules,” admits Thanissaro. “But then, living in the community, I saw how well designed they were. They not only serve to help and protect the monks, but the people around them as well.” Thanissaro has held to those rules faithfully since his ordination 17 years ago.

Recently he translated from the Pali the voluminous “Buddhist Monastic Code,” a comprehensive guide to 227 precepts that, along with detailed chapters on dealings with women, clothing, food, and diplomacy, also includes admonitions against eavesdropping, tickling, and stopping in the village to talk of kings, robbers, ministers of state, armies, or scents. But in his introduction Thanissaro suggests the real import of the Vinaya: they are not just “rules” but “qualities developed in the mind and character” of those practicing the dharma. lt is as a way of being in the world that the Vinaya finds its real meaning.

Though the Theravada has been faulted by Other Buddhist schools for not actively attending to the practice of compassion, Thanissaro points out that adhering to the Vinaya and devoting oneself to meditation creates, of necessity, a more compassionate person. The way Theravada monks live, being totally dependent on what is given them, is a situation in which both givers and receivers are able to act with generosity and humility.

THE DAILY GIVING AND RECEIVING OF ALMS is a mark of this practice. Early in the morning, amid the sound of blue jays and laughter, Thai women in black skirts and white blouses squat on the linoleum floor of the kitchen, chatting and drinking instant coffee. Outside a few of the men are smoking cigarettes as they wait for the rice to finish cooking.

This Thai family (one always seems to be in attendance) is overseeing the preparation of the food that we will offer as alms to Thanissaro and a young Thai monk, Path Phai Thita Bho. Wide rice noodles and fish, watermelon, mango and raisins arranged in bright patterns, soup, some salads, whole fruits and biscuits and cookies and flowers, and rice mounded up in elaborate aluminum serving bowls.

When the monks are spotted on the path between the rows of avocado trees we line up with our offering of rice, and we bow. The monks stop in front of each person as they place their portion of rice into the metal alms bowls (rice has become the symbolic offering of all the foods). Then the two monks turn deliberately, without hurrying, and disappear again into the avocado forest.

The twentieth century floods back in as a yellow Lincoln Continental screeches into place in front of the kitchen and the remainder of the elaborate feast on the table is quickly loaded into its capacious trunk. The trunk is slammed shut and the car races down to the table by the shrine room where the monks eat first from the vast feast, and then the laypeople finish whatever is left.

“When I talked with Ajahn Fuang about going back to the West, about taking the tradition to America, he was very explicit. ‘This will probably be your life’s work,’ he said. He felt, as many teachers have, that the forest tradition would die out in Thailand but would then take root in the West.”

As we walk along one of the dusty perimeter paths of the property, Thanissaro points out the native flora he is beginning to know and talks of the future. Currently he is translating many of the “forest teachings” into English.

He is also the author of The Mind Like Fire Unbound, a scholarly exploration of the Pali canon in relation to the Buddhist term nirvana, which literally means “the extinguishing of a fire.” For Thanissaro, the original meaning of nirvana is the “unbinding” or freeing of a fire from its fuel, rather than “extinguishing.” Once unbound, the fire “remains” in some other nascent state. One Buddhist scholar called Thanissaro’s understanding “too original”; others have welcomed its important implications.

It seems appropriate that “unbinding” would be a theme in Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s teachings. After all, he has unbound himself from several cultures, and unbinding (from the city, from habits, from popular Buddhist trends) is at the core of the forest tradition in which he trained.

As we walk, Thani bends periodically to check the progress of his newly planted trees. Native trees—California walnut, scrub oak, and digger pine—no more than a foot or so high now, they’re barely visible in the waisthigh chaparral. These trees grow naturally on the edge of the California desert, not dependent on irrigation or human care to survive. Thanissaro has planted them with the hope that they will eventually replace the avocado orchard altogether. When that happens the Metta Forest will be in America to stay: a wild forest, yet a native one, able to thrive and spread on its own.

The Rewards of the Contemplative Life

SAMANNAPHAIA SUTIANTA

Adapted from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

SHAKYAMUNI BUDDHA

There is the case where a Tathagata (the Buddha) appears in the world, worthy and rightly selfawakened. He teaches the Dhamma admirable in its beginning, admirable in its middle, admirable in its end. He proclaims the holy life both in its particulars and in its essence, entirely perfect, surpassingly pure.

A householder or householder’s son, hearing the Dhamma, gains conviction in the Tathagata and reflects: ‘Household life is crowded, a dusty path. The life gone forth is like the open air. It is not easy living at home to practice the holy life totally perfect, totally pure, like a polished shell. Suppose I were to go forth?’ So after some time he abandons his mass of wealth, large or small; leaves his circle of relatives, large or small; shaves off his hair and beard, puts on the saffron robes, and goes forth from the household life into homelessness.

When he has thus gone forth, he lives restrained by the rules of the monastic code, seeing danger in the slightest faults. Consummate in his virtue, he guards the doors of his senses, is possessed of mindfulness and presence of mind, and is content.

Now, how does a monk guard the doors of his senses? On seeing a form with the eye, he does not grasp at any theme or variations by which—if he were to dwell without restraint over the faculty of the eye-evil—unskillful qualities such as greed or distress might assail him. (Similarly with the ear, nose, tongue, body, and intellect.)

And how is a monk possessed of mindfulness and presence of mind? When going forward and returning, he acts with full presence of mind. When looking toward and looking away . . . when bending and extending his limbs . . . when carrying his outer cloak, his upper robe, and his bowl . . . when eating, drinking, chewing, and tasting. . . when urinating and defecating . . . when walking, standing, sitting, falling asleep, waking up, talking, and remaining silent, he acts with full presence of mind.

And how is a monk content? Just as a bird, wherever it goes, flies with its wings as its only burden; so too is he content with a set of robes to provide for his body and almsfood to provide for his hunger. Wherever he goes, he takes only his barest necessities along.

He seeks out a secluded dwelling: a forest, the shade of a tree, a mountain, a glen, a hillside cave, a charnel ground, a jungle grove, the open air, a heap of straw. After his meal, returning from his almsround, he sits down, crosses his legs, holds his body

erect, and brings mindfulness to the fore. He purifies his mind from greed, ill will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and anxiety, and uncertainty. As long as these five hindrances are not abandoned within him, he regards it as a debt, a sickness, a prison, slavery, a road through desolate country. But when these five hindrances are abandoned within him, he regards it as unindebtedness, good health, release from prison, freedom, a place of security. Seeing that they have been abandoned within him, he becomes glad, enraptured, tranquil, sensitive to pleasure. Feeling pleasure, his mind becomes concentrated.

Quite withdrawn from sensual pleasures, withdrawn from unskillful mental qualities, he enters and remains in the first jhana (mental absorption): rapture and pleasure born of withdrawal, accompanied by directed thought and evaluation. He permeates and pervades, suffuses and fills this very body with the rapture and pleasure born of withdrawal. Just as if a skilled bathman or bathman’s apprentice would pour bath powder into a brass basin and knead it together, sprinkling it again and again with water, so that his ball of bath powder—saturated, moistureladen, permeated within and without—would nevertheless not drip; even so, the monk permeates . . . this very body with the rapture and pleasure born of withdrawal. There is nothing of his entire body unpervaded by rapture and pleasure born of withdrawal. This is a reward of the contemplative life, visible here and now, more excellent than the previous ones and more sublime.

Furthermore, with the stilling of directed thought and evaluation, he enters and remains in the second jhana: rapture and pleasure born of composure, one-pointedness of awareness free from directed thought and evaluation—internal assurance. He permeates and pervades, suffuses and fills this very body with the rapture and pleasure born of composure. Just like a lake with spring-water welling up from within, having no inflow from east, west, north, or south, and with the skies supplying abundant showers time and again, so that the cool fount of water welling up from within the lake would permeate and pervade, suffuse and fill it with cool waters, there being no part of the lake unpervaded by the cool waters; even so, the monk permeates . . . this very body with the rapture and pleasure born of composure. There is nothing of his entire body unpervaded by rapture and pleasure born of composure. This, too, is a reward of the contemplative life, visible here and now, more excellent than the previous ones and more sublime.

And furthermore, with the fading of rapture, he remains in equanimity, mindful and fully aware, and physically sensitive of pleasure. He enters and remains in the third jhana, and of him the Noble Ones declare, ‘Equanimous and mindful, he has a pleasurable abiding.’ He permeates and pervades, suffuses and fills this very body with the pleasure divested of rapture. Just as in a lotus pond, some of the lotuses, born and growing in the water, stay immersed in the water and flourish without standing up out of the water, so that they are permeated and pervaded, suffused and filled with cool water from their roots to their tips, and nothing of those lotuses would be unpervaded with cool water; even so, the monk permeates . . . this very body with the pleasure divested of rapture. There is nothing of his entire body unpervaded with pleasure divested of rapture. This, too, is a reward of the contemplative life, visible here and now, more excellent than the previous ones and more sublime.

And furthermore, with the abandoning of pleasure and stress—as with the earlier disappearance of elation and distress—he enters and remains in the fourth jhana: purity of equanimity and mindfulness, neither pleasure nor stress. He sits, permeating the body with a pure, bright awareness. Just as if a man were sitting covered from head to foot with a white cloth so that there would be no part of his body to which the white cloth did not extend; even so, the monk sits, permeating the body with a pure, bright awareness. There is nothing of his entire body unpervaded by pure, bright awareness. This, too, is a reward of the contemplative life, visible here and now, more excellent than the previous ones and more sublime.

With his mind thus concentrated, purified, and bright, he directs it to the knowledge of the ending of the mental fermentations. Just as if there were a pool of water in a mountain glen—clear, limpid, and unsullied—where a man with good eyesight standing on the bank could see shells, gravel, and pebbles, and also shoals of fish swimming about and resting, and it would occur to him, ‘This pool of water is clear, limpid, and unsullied. Here are these shells, gravel, and pebbles, and also these shoals of fish swimming about and resting.’ In the same way, the monk discerns, as it is actually present, that ‘This is stress. . . This is the origination of stress. . . This is the stopping of stress. . . This is the way leading to the stopping of stress. . . These are mental fermentations. . . This is the origination of fermentations. . . This is the stopping of fermentations . . . This is the way leading to the stopping of fermentations.’ His heart, thus knowing, thus seeing, is released from the fermentations of sensuality, becoming, and ignorance. With release, there is the knowledge, ‘Released.’ He discerns that ‘Birth is ended, the holy life fulfilled, the task done. There is nothing further for this world.’ This, too, is a reward of the contemplative life, visible here and now, more excellent than the previous ones and more sublime. And as for another visible fruit of the contemplative life, higher and more sublime than this, there is none.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.