“Where is Tibet?” Following the Chinese conquest, the song of Tibet seems, at times, as constant as a prayer wheel: the Real Tibet has been lost, it goes; the Real Tibet is gone.

Well, where did it go? To judge by the current coverage of Tibet in the press, the Real Tibet has ended up in Hollywood. Between Seven Years in Tibet and Kundun, it would seem that if the Dalai Lama and his people are getting a public hearing anywhere in this country for their very real problems, it’s at the headquarters of the illusion industry.

How much of a boon this represents for the cause of Tibet is open to question. But the movies are still one of the most important ways through which Americans develop their opinions about the rest of the world. And how Tibet fares in the representational sphere of images and public consciousness is relevant-maybe even critical-to its fortunes in the political sphere.

If the Real Tibet has come to roost in Hollywood, it is not without irony, for the mythologized version that most piqued the appetite of Westerners began on a Columbia Pictures backlot. Ever since 1937, when Frank Capra directed Lost Horzion, media representations of Tibet have had to contend with his portrait of a Himalayan utopia. For some sixty years, the studios have kept alive a False Tibet. It’s one whose legacy may prove hard to shake.

Capra’s film, based on James Hilton’s novel, opens with an airplane evacuating foreigners from troubled “Baskul” -an Asian locale fabricated in the image of civil-war-ridden China. After a mysterious crash landing into a Himalayan snowbank, the passengers are offered hospitality by gentle lamas from the monastery of Shangri-La. The leader of the stranded group, a British diplomat played by Ronald Colman, discovers that he and his companions have been kidnapped, with the help of the pilot, in an effort to augment the isolated community with new talent. Attrition seems to be this Eden’s only threat.

The rift between the embattled chaos of the outside world and the serenity of the remote sanctuary provides the story with much of its dramatic tension. Could it be that these sagacious Tibetans have it all figured out, up there in the mountains, where they live free of wars, strikes, mortgages, and emphysema? Could it be that they are smarter than us? The lamas even talk down to the white folks.

But wait a second—the lamas are white folks. Not only are the monastics of the story largely European expatriates, the Head Lama himself is an unspeakably old Belgian Catholic priest, played by Sam Jaffe.

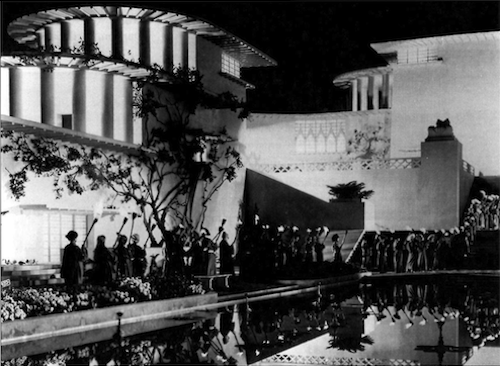

He runs his Buddhist monastery on a sort of denatured essence of Christian ethics. Through Capra’s lens, the monastery headquarters, a confection in Bakelite, looks like a country club in California. That which represents the cultural Other-that which is farthest away, most alien, an inaccessible haven-has been cast in the image of middle-class white America.

Shangri -la’s antithesis, war-ravaged Baskul, depicts a more typical Asian location, despotic and barbarous. For if Shangri-La was the lost horizon, Baskul was what the West in the thirties saw just beyond the real horizon: war and upheaval, cast-in the purest orientalist tradition-in the image of Asia. In contrast, the Tibet of Lost Horizon remains a decidedly homegrown fantasy-equal parts Kansas and Over the Rainbow. Truly remote, historically inaccessible to the West, the country in 1937 must have seemed to Capra as blank as an empty lot.

Thus was born the myth of Shangri-La: a hidden refuge divorced from history and geography, a place where you could truly get away—if only you could get there at all.

With the release of Seven Years in Tibet and Kundun, Tibet has come a long way from this exile in the land of shows. The appeal of Tibet is no longer contingent on its sequestration from world news. What with the personal popularity of the Dalai Lama, the burgeoning interest in Buddhism in the West, and Tibet the ongoing victim of China’s human-rights abuses and the most salient symbol of those abuses, Tibet is world news.

Nevertheless, the fact that it takes an Aryan idol like Brad Pitt to drive this point home tells us more than we might want to know about the priorities of the hard news media. Another nun raped and tortured by the Chinese; another temple razed; the methodical annihilation of a culture-that’s just not sexy enough to make the cut. But if the news media has abdicated its job to Hollywood, it has reasserted its authority by suggesting that Tibet is now tarnished by its association with Tinseltown.

Holier-than-thou journalists have taken potshots at the Dalai Lama for his attendance at Hollywood parties—as if he had chosen them over state dinners at the White House. While Melissa Mathison and Martin Scorsese of Kundun and Becky Johnston and Jean- Jacques Annaud of Seven Years (not to mention Richard Gere) have vocalized more genuine concern for the people of Tibet than President Clinton, the print media undermines their efforts with a one-two punch: puff up their involvement with Buddhism or the Free Tibet movement until coverage of their celebrity overshadows their cause; and then run dismissive headline stories on “Hollywood Chic.”

Hollywood’s efforts at track-two diplomacy are all the more laudable in the absence of any alternative from the Oval Office. With Clinton reneging on human rights issues and with China displaying a frustratingly insouciant arrogance with regard to world opinion, making Tibet a populist cause may be the country’s only hope.

Viewers looking for the old stereotypes in the new movies will not be disappointed. Neither Kundun norSeven Years exposes the feudal underbelly of Tibet, a hierarchical society of whose inequities the Dalai Lama himself has been an outspoken critic. For Western historians of the Real Tibet, this selective oversight will be enough to put these movies in a continuum with Lost Horizon. And at the same time, pragmatic exiles and scholars tell us that the Real Tibet is gone, that it’s too late for Hollywood to save Tibet, that the Chinese devastation is irreversible; thus reducing professional Free Tibet activists to latter-day orientalists in love with their own heroic quest and the rhetoric of an exotic paradise—a horizon—lost.

But in one crucial regard, this new generation of movies does offer a Real Tibet. Both stories are anchored in a real historical context and animated by the very real process of genocide. This time, if Hollywood has gotten one thing right, it’s this: there is no horizon left to run to.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.