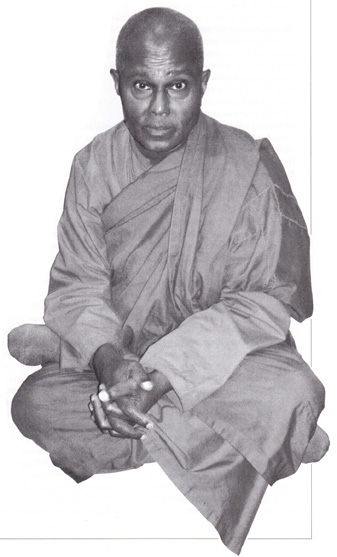

Ordained at age twelve in Kandy, Sri Lanka, the Venerable Henepola Gunaratana trained as a novice for eight years and as a bhikkhu (monk) for seven years before leaving Sri Lanka in 1954 to work with untouchables in India. In 1968 he came to the United States and became the Honorary General Secretary of the Buddhist Vihara Society, an urban monastery in Washington, D.C., while earning a Ph.D in Philosophy from the American University, where he later served as the Buddhist chaplain. He has been teaching Buddhism and conducting meditation retreats in Southeast Asia, North America, Europe, Mexico, and Australia for over forty years. His books include Mindfulness in Plain English from Wisdom Publications (see article here). In 1988, Bhante Gunaratana became President of the Bhavana Society in High View, West Virginia, a center to promote meditation and the monastic life. This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Helen Tworkov at the Bhavana Society last November. Bhante is a Pali word equivalent to Reverend in English.

Tricycle: When colleagues from Sri Lanka visit your community here in West Virginia, what do they find most surprising?

Bhante Gunaratana: That we allow monks and nuns to work together. They may not approve of that.

Tricycle: Nowadays, in the West, many people find that hierarchical distinction between the monastics and the laity outdated, old-fashioned; something that developed in Asia but that has no place in the West.

Bhante Gunaratana: The monastic path is better, not in a political sense or as a power structure, but better for spiritual growth. Monasticism nourishes, supports a frame of mind for practice. You cannot have a cake and eat it at the same time. If you want to live in a non-monastic community, it cannot be called monastic, and you cannot expect to do the practice in the best way. Life today has so many commitments, and people get into very difficult situations, emotionally and otherwise. Everyone has so many things to do. You have to have a space to grow, to improve your spiritual practice. That is why the Buddha said, “Have few duties.” When you have few duties, you have time to practice, you are not all the time tense, uptight, rigid and nervous, worrying and destroying your health.

Tricycle: Are there ways of encouraging a monastic life in modern times?

Bhante Gunaratana: To update the monastic tradition, people don’t have to be totally cut off from their societies. Even in monastic lives, there are certain things that people can do in order to make it more lively. In early days, monastic life seems to have been very grueling, very dark. The monks sat under trees or in caves and meditated all the time. One of the accusations that we get here from some very strict monastic people is that we are too relaxed. Not to the degree that we have lost sight of monasticism, but that we try to update it by making certain adjustments.

Tricycle: Such as?

Bhante Gunaratana: As I mentioned, we drive if necessary. Sometimes we go shopping if there is nobody else to go. And we have monks and nuns living in the same place. As long as we maintain our discipline and rules, these adjustments are possible. Sometimes people say, all religious principles—not only monastic principles—are out-of-date, that all religious discipline is out-of-date. Morality is no longer an important issue in some places, some societies, because people do not want to discipline themselves. They do not want to be responsible, honest, sincere. But honesty, sincerity, responsibility never become out-of-date. We want to preserve the essence. Compromise doesn’t mean to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Every rule prescribed by the Buddha is for our own benefit. Every precept we observe is in order to cleanse the mind. Without mental purification, we can never gain concentration, insight, wisdom, and will never be able to remove psychic irritations.

Tricycle: In the West there is a pervasive psychological perspective which suggests that celibacy is unhealthy and therefore that monasticism attracts not people inspired by a spiritual quest, but those with sexual problems.

Bhante Gunaratana: At the same time, we can see that people who are obsessed with sex are always in trouble. Everywhere. Getting involved in all these natural urges and giving in to them is also not healthy. Somebody who very carefully, mindfully trains himself to restrain himself, to discipline himself, can live a very healthy life. People try to justify greed, hatred, and delusion. Many people become gullible.

Tricycle: Gullible?

Bhante Gunaratana: You know, “gullible” is a very beautiful Pali word. In Pali, it is called galibaliso.Gali means swallow, baliso means bait. When you have the attitude that you don’t have to discipline yourself, that whenever you feel a sex urge, you can go and have sex with anybody you like; that when you get angry, you can express it any way you want, and even use violence if you like. These kinds of attitudes lead society downhill. I feel that is what is happening. Trying to introduce discipline, sincerity, honesty, religious practices and so forth—that kind of work has become like trying to stop a stream with a piece of paper. Our mind is like liquid. Liquid always goes down. It never goes up by itself, by its own force. Similarly, the mind always goes to the wrong thing. This is why the Buddha said the real practice of dharma is like “going upstream.” Not an easy job.

Tricycle: Is that just as true in or out of the monastery?

Bhante Gunaratana: Yes, but the sole purpose of monasticism is to give a chance to people to discipline themselves. It is like a laboratory. We don’t want every nook and corner to have laboratories, but there have to be some laboratories—some sort of controlled atmosphere for a person to grow—if that person really wants to be disciplined for the sake of his or her own inner peace. America is still like a teenager, a juvenile, just trying to grow, and that spiritually immature state has been taken as a standard for the whole world to follow. I don’t think that is a healthy way of thinking. Not respecting anybody should not be the standard. Trying to be equal is a wonderful thing, but only when we attain our state of responsibility and freedom are we all equal.

Tricycle: We are not born equal?

Bhante Gunaratana: We are not born equal, are not created equal. We are divided by karma. We are born different, and live different, and die different, because of our different karma. Karma divides us into high and low, rich and poor, intellectual and non-intellectual, attractive and non-attractive, skillful and non-skillful, and so forth and so on. But there are certain areas where things become equal. When somebody comes to the order of monks and nuns, they give up their distinctions and become equal. When they attain stages of enlightenment, they all are equal. There is no difference in the attainment of enlightenment. When we attain nirvana, we all are equal.

Tricycle: The Theravada tradition has a long history of inequality between the sexes, even within the realm of spiritual understanding. In fact, it is my understanding that women cannot attain full ordination in your tradition.

Bhante Gunaratana: That is an adjustment that I would like to propose. We’ve had a problem in introducing fully ordained nuns into the order. It has become a very big controversy because many women would like to enter the Theravada nuns’ order, and receive full ordination, but that has not been possible so far.

Tricycle: Where is the opposition coming from today?

Bhante Gunaratana: From the Theravada Buddhist school.

Tricycle: Because of the traditional ways?

Bhante Gunaratana: Yes. Actually, the tradition for fully ordained women once existed, but has disappeared. It was there at the time of the Buddha.

Tricycle: How are Theravada nuns ordained now?

Bhante Gunaratana: It is not a full ordination, but a novice ordination.

Tricycle: Aren’t there nuns in southeast Asia who go to Mahayana Buddhist countries to receive the full ordination?

Bhante Gunaratana: Yes, but if they come back to Sri Lanka or Thailand, it’s not recognized. In a country like the United States, which is a neutral country where Buddhism is still new, full ordination for women should be established.

Tricycle: What do your brothers in Sri Lanka think about your supporting this proposition? Do they think, “Oh, maybe he has just spent too much time in the West”?

Bhante Gunaratana: [laughing] Yes. Yet in one famous discourse, the Kalana Sutta, the Buddha says, “Don’t believe in tradition, don’t believe in mere hearsay. Don’t accept anything because things are in the scriptures. Don’t accept anything because the teacher appears to be a very honorable, sincere person. Don’t accept anything because it appeals to intellect—to logic or philosophy. Don’t accept anything because you like it. Check with your own experience. Investigate, discuss, meditate upon, and question. And then, if what you learned is good for yourself, good for others, good for both, then accept it. If it is not good for you, not good for others, not good for both—reject it.” So the freedom of inquiry is very strongly advocated by the Buddha. And, therefore, using that information, I make these suggestions, these recommendations.

Tricycle: I’m sure that many women in the West and in Asia will be very appreciative of this view. And yet, even in those societies that sanction full ordination for women, the rules for women are still twice as many as for men, and the women are still considered inferior to the men. Even here, I have observed that the men leave the meditation hall before the women, and that they are served food first.

Bhante Gunaratana: We don’t have fully ordained nuns. The women here are all novices. In monastic hierarchy, whoever has stayed in the order the longest is considered to be the senior-most person, and that person leads the group. He goes first. He sits first and so forth. The hierarchy is established only by seniority.

Tricycle: If nuns’ full ordination were reestablished, would you also support full equality between men and women?

Bhante Gunaratana: I support it. I support it. Fully ordained nuns should be able to do the same thing as fully ordained monks. That’s the kind of equality I support. The Buddha introduced extra rules for women, because without giving some concessions, without introducing some rules, there would have been an enormous upheaval—opposition coming from other monks as well as laypeople. To silence them, he introduced these regulations. But in modern society these things can be modified.

Tricycle: Do you think that the changes that you recommend can be adapted in Asia?

Bhante Gunaratana: My strong hunch is that in Asia full ordination will never happen because the tradition, the habit, is so strong that they don’t want to change it. The only possibility exists in societies like this one, where Buddhism is new. Once it is established here, then, perhaps, slowly it can be introduced to Asian Buddhist communities.

Tricycle: What are the things that you think should not be adjusted, that you think must not change?

Bhante Gunaratana: Dharma can be translated into simple, modern, current language. But the meaning should not be changed to suit people’s requirements. Some aspects of the rituals can change but, for instance, wearing robes must not change. Even in the time of the Buddha, civilian dress was quite different from monks’ robes. And it is the same today. This robe protects us. As human beings we are not perfect. And when we have the robe, it reminds us of our place, and stops us from getting into wrong situations, wrongdoing.

Tricycle: Other Theravada communities have altered certain traditions, such as chanting only in Pali, or not eating after twelve noon; why have you chosen to preserve these rituals?

Bhante Gunaratana: If we do not continue these traditions, they will totally disappear. Buddha gave a beautiful little analogy. Suppose there is a drum used to summon people. And if there is a loose spot on the drum, somebody puts a peg in it. Then another spot becomes loose, and another peg gets put in. And then the third place becomes loose, and another peg. Eventually, the whole face of the drum will disappear. The face of the drum will be full of pegs. You can never see the drum, never know what the drum is. Similarly, if you do not preserve the form of Theravada Buddhism, the original form, eventually people won’t even know what it is.

Tricycle: What most distinguishes the Theravada tradition from the other great vehicles of Buddhism?

Bhante Gunaratana: The Theravada tradition tries to maintain the Buddhism presented in the Pali texts. It emphasizes morality, concentration, and wisdom practice as close to the Buddha’s own teaching as possible, without interpreting them, distorting them, or translating them into different ideas. As Theravada Buddhists, we are trying to preserve the Pali language and use it in our dharma sermons, in our daily devotional services.

Tricycle: And the benefit is maintaining the language of the Buddha?

Bhante Gunaratana: Yes. The benefit is that when you have any doubt about the teaching, any gray area, you can always go to Pali. And always you keep Pali as your reference language, in order to clarify certain dharma terms. If you do not have that kind of background, or that kind of reference, you have to rely on translations. If the translator has made a mistake, it is carried on generation after generation. That is what has happened to some other branches of Buddhism. Because they don’t study the original language, they have to read the third, fourth, fifth, sixth interpretations, or translations, and sometimes they lose track of the original teaching. Original teaching is preserved in the Pali tradition. No question about it.

Tricycle: Many people feel that the absence of the Bodhisattva Vow in the Theravada—the vow to save all sentient beings and to place others before oneself—diminishes the role of compassion that we find in some of the other traditions. Can you address that?

Bhante Gunaratana: You know, while we are trying to attain enlightenment, we must help others. We cannot wait. Suppose we are going on a journey, and somebody on the way needs some help—food, water, or somebody is sick and so forth. We cannot simply say, “Oh, I am going on a journey, you have to wait until I finish the journey.“ You cannot say that. You’ve got to help that person. That is your human, moral obligation. That is what the Buddha did. He became perfect by doing what he was supposed to do. He practiced in human society, with other people. Teaching, preaching, helping, serving, and doing everything that he had to do to help the world. And that helping, that practice, reached perfection. We don’t have to wait until we have attained enlightenment.

Tricycle: Do you think that some Westerners misunderstand Theravada Buddhism because of the absence of an actual Bodhisattva Vow?

Bhante Gunaratana: Exactly. Although Theravada Buddhists don’t have any special Bodhisattva Vow, in practice it is almost impossible to ignore helping others. And you know, this idea of helping others is not only Buddhist. Is there anything Buddhist in generosity? You don’t even have to be a human being to practice generosity. You might have seen animals sharing their food with other animals. To make this kind of distinction between Mahayana and Theravada is not a very practical, realistic way of seeing things. The challenge is making people understand the basic teachings, like selflessness, soulessness, and non-believing in a creator God. The first aspect, you know, impermanence, is really easy. If you read any book on physics, chemistry, or science, you will learn all about impermanence. But selflessness and not believing in a creator-God, these two are extremely difficult to teach.

Tricycle: Can a society as a whole become a little less egotistical, or is it only a matter of individual practice?

Bhante Gunaratana: It is individual practice, actually. Even when the Buddha attained enlightenment, greed, hatred, and delusion were not less than they are today. His sole purpose in attaining enlightenment was to serve the world. But as soon as he attained enlightenment, he became so disappointed. He thought, “How can I teach this dharma to these people? They are so full of ignorance, greed, hatred, jealousy, fear, tension, worry, and lust—how can they understand this?“ But he started teaching. And he was never able to eliminate all the suffering in the human world. Never. He eliminated the suffering of certain people, but compared to the number of people in the world, the number of people he helped to attain enlightenment is insignificant. Now, with more population, more desirous things produced by technological advancement, more things to promote your desire, promote your greed, selfishness, fear, tension, worry, it is therefore actually more difficult to practice pure dharma. And this is not just the problem of the dharma, of the teaching of the Buddha. This is the problem of all religions. Religious people are trying, as much they can, in their own limited capacities. At the same time, in the material world, other people are trying to promote their own productions, increase people’s greed. There are more televisions, more computers, more this, more that. So you have to compete with this.

Tricycle: How can the dharma best be protected in this environment?

Bhante Gunaratana: One who protects the dharma will be protected by the dharma, just like one who protects an umbrella will be protected by the umbrella. To protect the dharma, what should one do? Each and every individual must practice it. To the degree and extent a person practices dharma, to that degree and extent that person gets protection from the dharma. We can never get protection from anything else, no matter how much security, or insurance, or how many secure locks we have—never.

Tricycle: Do you have a goal for yourself?

Bhante Gunaratana: I say that Buddhism is like a tree. A tree has its canopy, leaves, flowers, you know, little branches, and the trunk, and the bark, and softwood and hardwood, the roots, and so forth. And we should want the hardwood, the pit, of the dharma, just like wanting the pit of a tree. Everything else can conceal the truth. There are so many things around the true dharma. And people can easily get deluded, confused, misled by those very many, many varieties of things. The Buddha said very clearly, “Until artificial gold appears in the market, pure gold shines. As soon as the artificial gold appears in the market, nobody knows which is pure gold, and which is artificial.“ So I want to show people this pure gold, so that they cannot be deluded by everything that glitters. That is my purpose.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.