Stephen Addiss, PhD, is Professor of Art at the University of Richmond in Virginia. Author of The Art of Haiku, one of Tricycle’s picks for “Books in Brief” this issue, Addiss is a prolific scholar-artist who has been practicing Japanese calligraphy and ink painting for over 40 years. He is a true jack-of-all-trades—Addiss also studied music under the tutelage of John Cage and toured internationally for 16 years as part of the folk duo “Addiss & Crofut.” Tricycle’s Emma Varvaloucas spoke with him by phone last month about his recently published book and his thoughts on the “haiku spirit.”

Stephen Addiss, PhD, is Professor of Art at the University of Richmond in Virginia. Author of The Art of Haiku, one of Tricycle’s picks for “Books in Brief” this issue, Addiss is a prolific scholar-artist who has been practicing Japanese calligraphy and ink painting for over 40 years. He is a true jack-of-all-trades—Addiss also studied music under the tutelage of John Cage and toured internationally for 16 years as part of the folk duo “Addiss & Crofut.” Tricycle’s Emma Varvaloucas spoke with him by phone last month about his recently published book and his thoughts on the “haiku spirit.”

You’ve been doing Japanese calligraphy and ink painting for over 40 years. How has your work changed over that long period of time? Well, I started by being interested in Chinese and Japanese painting and calligraphy historically. Since I always felt that the best way to learn about something is to try it yourself, I started practicing, and I must say I was absolutely terrible. [Laughs] I kept going anyway, and it gradually got better over the years. I studied with a Chinese gentleman in New York and then with a Japanese calligrapher in Japan. I just kept doing it out of the fun of it, and one day I looked at it, and I looked at it, and it wasn’t so terrible anymore. I had progressed all the way up to mediocrity! So once I reached that point, I realized that I could go ahead, and I kept going. So I’ve been going for, yes, 40 years now.

Have you found that your attitude towards creating art has changed over that time? Yes. At first, I was just trying to master the many difficult forms and all the possible variations of scripts and style that there were. As time has gone by, I’ve gotten less worried about mastering every kind—because that’s impossible, and nobody has ever done it anyway—and just did calligraphy as more to the spirit that I felt in it that day. It became more of a personal art as time went by.

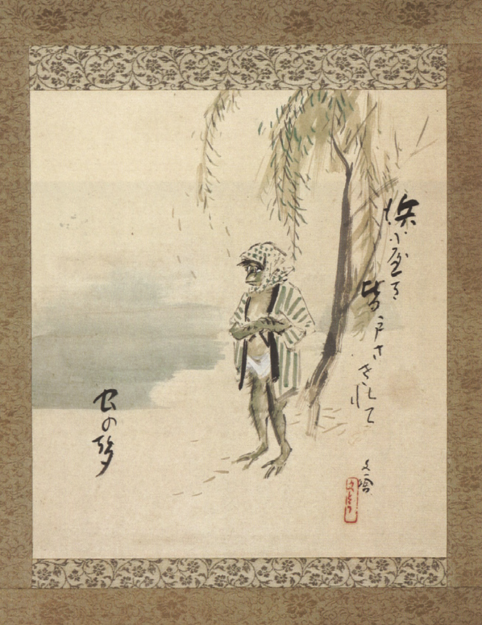

Let’s talk about your new book, The Art of Haiku. Something that I learned about for the first time when I read it was haiga, haiku paintings. The word ga means painting; how zenga means Zen painting, haiga means haiku painting. It’s interesting, because not that many people know about it, even in Japan. It turns out that almost all the haiku poets of the past, like Basho, did haiga. But haiga hasn’t become as famous as the written haiku that they did, partly because it’s harder to reproduce.

Do you have a favorite haiga painter? Probably the greatest haiga painter was Buson, because he was a great painter anyway. He’s one of the rare cases of somebody who’s considered one of the world’s great painters and one of the world’s great poets at the same time. Lots of painters do poetry, and lots of poets do some painting. But he’s one of the rare ones, maybe the most rare, who has really excelled at the very, very, very top of both painting and poetry. Of course, I’m also very fond of Issa, and Issa was not a very good painter. But he had a very simple, childlike, direct, personal quality that I like very much. So we learn from him that you don’t have to be an expert painter to be a good haiku painter.

One thing that’s very fine about haiku is that it takes away the things that aren’t necessary, leaving what’s very simple there. One reason why maybe it’s not more popular in the West is that we tend not to think that simple things can be so important or so beautiful, or at least some of us think that a thing should be complicated and highly technique-oriented. But in fact, something very simple is very difficult to do. Mozart’s a good example. Some of his music seems fairly simple and yet, you know, there was only one Mozart.

What do you need to be a good haiku painter? I think the right spirit and freedom of the brush, which comes just from doing it. If you do calligraphy a lot, you get to be the master of the brush. It’s not like in the West, where you have to learn a whole new oil painting technique if you want to be a painter. In East Asia, you’ve already learned how to do calligraphy, so you’ve learned how to master the brush, and you can move very quickly on to painting.

You saying that you have to have the right spirit reminds me of something that you said in another interview once: “Moralizing and pontificating are the greatest enemies of a haiku spirit.” What is the haiku spirit? Haiku is not supposed to tell people how to act. In fact, it’s not even supposed to tell you things. It’s supposed to suggest things. So the haiku spirit is to suggest a sense of a bluebird flying in the sky, rather than saying, “There’s a bluebird.”; Or if you’re feeling sad, you wouldn’t say, “I’m feeling sad today”; instead, you might have an image that conveys sadness. So the haiku spirit, I think, is to express one’s feeling towards nature indirectly, or in a way that the reader can participate with.

Do you think it’s possible for a person to embody the haiku spirit or to live a life with haiku spirit in mind?Yes, I think so, and I think that people who do that aren’t necessarily even haiku poets. I think that the haiku spirit goes beyond the particular Japanese form into a way of life in which you have union with nature and a sense of combining one’s own personality with the world outside instead of trying to dominate it.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.