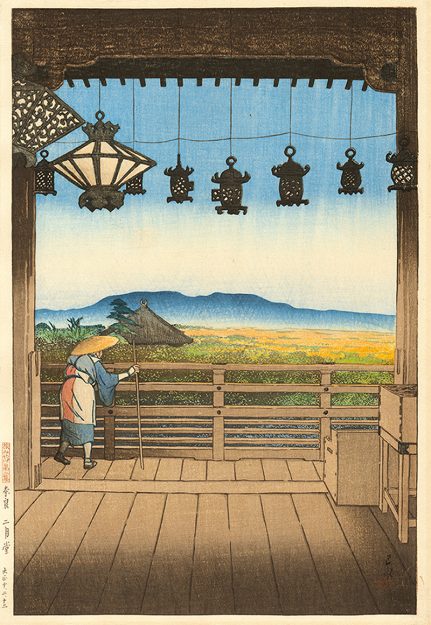

One of the most prolific printmakers of 20th-century Japan, Hasui Kawase designed nearly a thousand woodblock prints over the course of his lifetime. In his atmospheric depictions of Japan’s shifting landscapes, he combined traditional craftsmanship with modern aesthetics, drawing equally from the centuries-old techniques of Japanese woodblock printing and the innovations of modern European painting.

Born in Tokyo in 1883, Hasui dreamed of becoming an artist from a young age. His parents, the owners of a rope and thread company, urged him to take over the family business, but he was determined to stake his own path, inspired in part by his uncle, Kanagaki Robun, who had created the first manga magazine in 1874.

As a young man, Hasui began training under the painter Aoyagi Bokusen, managing the family business by day and studying painting and printing by night. When he was 26, the business went bankrupt, freeing him to pursue art full-time. He initially sought out Kiyokata Kaburaki, a leading master of nihonga, or Japanese-style painting, with the hopes of joining his studio; however, Kaburaki turned him away and encouraged him to instead study Western-style painting, known as yōga, to hone his craft. Over the course of the next two years, Hasui apprenticed dutifully under Okada Saburosuke, a master in the yōga style. When he applied again to study with Kaburaki, Kaburaki accepted him and bestowed upon him the name Hasui, a combination of the ideograms for his elementary school and his family name, which literally translates to “water gushing from a spring.”

Though Hasui’s prints are often tranquil, they do not attempt to hide or erase evidence of Japan’s industrialization, instead offering visions of serenity amidst modern life.

In 1918, after seeing an exhibition by the nihonga painter Shinsui Ito, Hasui approached Shinsui’s publisher, Shozaburo Watanabe, one of the founders of the shin-hanga (“new prints”) movement. This began a decades-long partnership between the two, and Hasui became one of the most prominent artists in the shin-hanga movement, which fused Western styles of painting with traditional Japanese techniques.

Shin-hanga emerged as an attempt to revitalize the Edo-era tradition of ukiyo-e woodblock printing, which had been in steady decline since the Meiji Restoration. But while previous masters of ukiyo-e focused on famous Japanese landmarks, Hasui opted for more ordinary scenes. And in contrast to the flat compositions of the Edo period, Hasui incorporated techniques from the European movements of Impressionism and Art Nouveau, particularly in his use of naturalistic lighting and texture. Though Hasui’s prints are often tranquil, they do not attempt to hide or erase evidence of Japan’s industrialization, instead offering visions of serenity amidst modern life. In discussing his decision to include electric wires and telephone poles in his compositions, he once said, “I don’t sketch subjectively but objectively. When I sketch, I can omit but I cannot deceive.” As a self-described realist, he was committed to capturing everyday life as he chronicled his country’s changing landscapes.

In collaboration with Watanabe, Hasui published a number of prints that were foundational to shin-hanga. In 1923, though, the pair faced unexpected setbacks when the Great Kanto earthquake destroyed Hasui’s house and Watanabe’s workshop, and all 188 of Hasui’s sketchbooks, as well as many of his woodblocks and prints, were lost. With his home and many of his works destroyed, Hasui began traveling around Japan, visiting the Hokuriku, San’in, and San’yo regions and creating sketches that became the basis for many of his later works. Through his subtle portraits of snowy villages and quiet urban scenes, he came to be known as the leading landscape printmaker of his time.

In 1956, at the age of 73, Hasui was recognized by the Japanese government as a Living National Treasure, making him the first print artist to receive this title. Initially, the Committee for the Preservation of Intangible Cultural Treasures had planned to honor both Hasui and Shinsui Ito with the award in 1953, but many raised objections about singling out individual printmakers due to the shared nature of the craft: A single print required close collaboration among the designer, engraver, and printer. “It requires telepathic communication,” wrote Hasui. “Unless all parties are completely in tune, the process will not work. When my mind and the minds of the artisans are in complete agreement, a good work can be generated.”

As a self-described realist, he was committed to capturing everyday life as he chronicled his country’s changing landscapes.

To honor this collaborative process, the committee commissioned Hasui to create a new print, with the plan to carefully document its production and recognize all the artisans involved. The result was Snow at Zojo-ji (pictured above), which was designated an Intangible Cultural Property in an effort to ensure that the tradition of woodblock printing would live on as the nation continued to modernize. “Almost everything is headed toward modernization. In the midst of this modern city, woodcut painting, done all by hand from beginning to end, is still going strong,” Hasui stated in a film produced the year before his death. “Thus, I am living in the world of two opposite natures.” Balancing tradition and modernity, Hasui’s prints bring together these two seeming opposites, presenting visions of tranquility in the midst of constant change.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.