On the nineteenth of January, 1939, five members of the Waffen-SS, Heinrich Himmler’s feared Nazi shock troops, passed through the ancient, arched gateway that led into the sacred city of Lhasa. Like many Europeans, they carried with them idealized and unrealistic views of Tibet, projecting, as Orville Schell remarks in his book Virtual Tibet, “a fabulous skein of fantasy around this distant, unknown land.” The projections of the Nazi expedition, however, did not include the now familiar search for Shangri-La, the hidden land in which a uniquely perfect and peaceful social system held a blueprint to counter the transgressions that plague the rest of humankind. Rather, the perfection sought by the Nazis was an idea of racial perfection that would justify their views on world history and German supremacy.

What brings about this odd juxtaposition of Tibetan lamas and SS officers on the eve of World War II is a strange story of secret societies, occultism, racial pseudo-science, and political intrigue. They were, in fact, on a diplomatic and quasi-scientific mission to establish relations between Nazi Germany and Tibet and to search for lost remnants of an imagined Aryan race hidden somewhere on the Tibetan plateau. As such, they were a far-flung expression of Hitler’s most paranoid and bizarre theories on ethnicity and domination. And while the Tibetans were completely unaware of Hitler’s racist agenda, the 1939 mission to Tibet remains a cautionary tale about how foreign ideas, symbols, and terminology can be horribly misused.

Some Nazi militarists imagined Tibet as a potential base for attacking British India, and hoped that this mission would lead to some form of alliance with the Tibetans. In that they were partly successful. The mission was received by the Reting Regent (who had led Tibet since the death of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama in 1933), and it did succeed in persuading the Regent to correspond with Adolf Hitler. But the Germans were also interested in Tibet for another reason. Nazi leaders such as Heinrich Himmler believed that Tibet might harbor the last of the original Aryan tribes, the legendary forefathers of the German race, whose leaders possessed supernatural powers that the Nazis could use to conquer the world.

This was the age of European expansion, and numerous theories provided ideological justification for imperialism and colonialism. In Germany the idea of an Aryan or “master” race found resonance with rabid nationalism, the idea of the German superman distilled from the philosophy of Frederick Nietzsche, and Wagner’s operatic celebrations of Nordic sagas and Teutonic mythology.

Long before the 1939 mission to Tibet, the Nazis had borrowed Asian symbols and language and used them for their own ends. A number of prominent articles of Nazi rhetoric and symbolism originated in the language and religions of Asia. The term “Aryan”, for example, comes from the Sanskrit word arya, meaning noble. In the Vedas, the most ancient Hindu scriptures, the term describes a race of light-skinned people from Central Asia who conquered and subjugated the darker-skinned (or Dravidian) peoples of the Indian subcontinent. Linguistic evidence does support the multidirectional migration of a central Asian people, now referred to as Indo-Europeans, into much of India and Europe at some point between 2000 and 1500 B.C.E., although it is unclear whether these Indo-Europeans were identical with the Aryans of the Vedas.

So much for responsible scholarship. In the hands of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European jingoists and occultists such as Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, these ideas about Indo-Europeans and light-skinned Aryans were transformed into a twisted myth of Nordic and later exclusively German racial superiority. The German identification with the Indo-Europeans and Aryans of the second millennium B.C.E. gave historical precedence to Germany’s imperial “place in the sun” and the idea that ethnic Germans were racially entitled to conquest and mastery. It also aided in fomenting anti-Semitism and xenophobia, as Jews, Gypsies, and other minorities did not share in the Aryan German’s perceived heritage as members of a dominant race.

Ideas about an Aryan or master race began to appear in the popular media in the late nineteenth century. In the 1890s, E. B. Lytton, a Rosicrucian, wrote a best-selling novel around the idea of a cosmic energy (particularly strong in the female sex), which he called “Vril.” Later he wrote of a Vril society, consisting of a race of super-beings that would emerge from their underground hiding-places to rule the world. His fantasies coincided with a great interest in the occult, particularly among the upper classes, with numerous secret societies founded to propagate these ideas. They ranged from those devoted to the Holy Grail to those who followed the sex and drugs mysticism of Alastair Crowley, and many seem to have had a vague affinity for Buddhist and Hindu beliefs.

General Haushofer, a follower of Gurdjieff and later one of Hitler’s main patrons, founded one such society. Its aim was to explore the origins of the Aryan race, and Haushofer named it the Vril Society, after Lytton’s fictional creation. Its members practiced meditation to awaken the powers of Vril, the feminine cosmic energy. The Vril Society claimed to have links to Tibetan masters, apparently drawing on the ideas of Madame Blavatsky, the Theosophist who claimed to be in telepathic contact with spiritual masters in Tibet.

In Germany, this blend of ancient myths and nineteenth-century scientific theories began to evolve into a belief that the Germans were the purest manifestation of the inherently superior Aryan race, whose destiny was to rule the world. These ideas were given scientific weight by ill-founded theories of eugenics and racist ethnography. Around 1919, the Vril Society gave way to the Thule Society (Thule Gesellschaft), which was founded in Munich by Baron Rudolf von Sebottendorf, a follower of Blavatsky. The Thule Society drew on the traditions of various orders such as the Jesuits, the Knights Templar, the Order of the Golden Dawn, and the Sufis. It promoted the myth of Thule, a legendary island in the frozen northlands that had been the home of a master race, the original Aryans. As in the legend of Atlantis (with which it is sometimes identified), the inhabitants of Thule were forced to flee from some catastrophe that destroyed their world. But the survivors had retained their magical powers and were hidden from the world, perhaps in secret tunnels in Tibet, where they might be contacted and subsequently bestow their powers on their Aryan descendants.

Such ideas might have remained harmless, but the Thule Society added a strong right-wing, anti-Semitic political ideology to the Vril Society mythology. They formed an active opposition to the local Socialist government in Munich and engaged in street battles and political assassinations. As their symbol, along with the dagger and the oak leaves, they adopted the swastika, which had been used by earlier German neo-pagan groups. The appeal of the swastika symbol to the Thule Society seems to have been largely in its dramatic strength rather than its cultural or mystical significance. They believed it was an original Aryan symbol, although it was actually used by numerous unconnected cultures throughout history.

Beyond the adoption of the swastika, it is difficult to judge the extent to which either Tibet or Buddhism played a part in Thule Society ideology. Vril Society founder General Haushofer, who remained active in the Thule Society, had been a German military attaché in Japan. There he may have acquired some knowledge of Zen Buddhism, which was then the dominant faith among the Japanese military. Other Thule Society members, however, could only have read early German studies of Buddhism, and those studies tended to construct the idea of a pure, original Buddhism that had been lost, and a degenerate Buddhism that survived, much polluted by primitive local beliefs. It seems that Buddhism was little more than a poorly understood and exotic element in the Society’s loose collection of beliefs, and had little real influence on the Thule ideology. But Tibet occupied a much stronger position in their mythology, being imagined as the likely home of the survivors of the mythic Thule race.

The importance of the Thule Society can be seen from the fact that its members included Nazi leaders Rudolf Hess (Hitler’s deputy), Heinrich Himmler, and almost certainly Hitler himself. But while Hitler was at least nominally a Catholic, Himmler enthusiastically embraced the aims and beliefs of the Thule Society. He adopted a range of neo-pagan ideas and believed himself to be a reincarnation of a tenth-century Germanic king. Himmler seems to have been strongly attracted to the possibility that Tibet might prove to be the refuge of the original Aryans and their superhuman powers.

By the time Hitler wrote Mein Kampf in the 1920s, the myth of the Aryan race was fully developed. In Chapter XI, “Race and People,” he expressed concern over what he perceived as the mixing of pure Aryan blood with that of inferior peoples. In his view, the pure Aryan Germanic races had been corrupted by prolonged contact with Jewish people. He lamented that northern Europe had been “Judaized” and that the German’s originally pure blood had been tainted by prolonged contact with Jewish people, who, he claimed, lie “in wait for hours on end, satanically glaring at and spying on the unsuspicious girl whom he plans to seduce, adulterating her blood and removing her from the bosom of her people.” For Hitler, the only solution to this mingling of Aryan and Jewish blood was for the tainted Germans to find the wellsprings of Aryan blood.

It may happen that in the course of history such a people will come into contact a second time, and even oftener, with the original founders of their culture and may not even remember that distant association. A new cultural wave flows in and lasts until the blood of its standard-bearers becomes once again adulterated by intermixture with the originally conquered race.

In the search for “contact a second time” with the Aryans, Tibet – long isolated, mysterious, and remote – seemed a likely candidate.

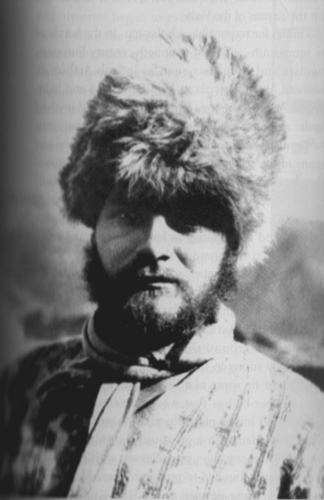

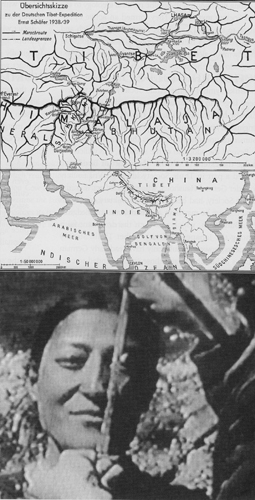

The leader of the German mission was Dr. Ernst Schaefer, a respected zoologist and botanist. He was accompanied by Dr. Bruno Beger, an anthropologist and ethnologist, Dr. Karl Wienert, a geophysicist, Edmund Geer, a taxidermist, and Ernst Krause, a photographer who at fifty was the eldest member of the group by more than a decade.

Ernst Schaefer was energetic, emotional, and ambitious. Born in 1910, he made his first journey to Tibet when he traveled on two scientific expeditions in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands in 1930-31 and 1934-36. On the first expedition, an American scientist, Brooke Dolan, accompanied Schaefer. Dolan was also to travel to Lhasa. In 1943, he accompanied Captain Ilya Tolstoy (the grandson of the Russian novelist) on a mission for the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA. We might suspect the Americans of keeping an eye on the German mission even in those early years, but no evidence of any intelligence involvement in those expeditions has yet emerged.

During the 1930s German scholars studied the material gathered on Schaefer’s early expeditions. This included Tibetan texts from both the Buddhist religion and that of the Bon faith (which in some form predates Buddhism in Tibet). The Nazis naturally had a particular interest in the Bonpo, in the hope that the elder beliefs preserved elements of ancient Aryan religion. But an understanding of the complex nature of Bon and its links to Buddhism lay far in the future and, while they must have hoped to uncover secrets within these texts, their studies of Bon proved of little benefit to the Nazis.

The ambitious Schaefer had developed a network of contacts during the 1930s. He had met the Panchen Lama on his Tibetan travels, and was in contact with most of the great explorers of Tibet and Central Asia. But Schaefer’s membership in the SS brought him his most important connection. His first Tibetan expedition attracted the attention of Heinrich Himmler, who became Schaefer’s patron. Himmler introduced him to SS leaders and to membership in the SS-Ahnenerbe, the Heritage of the SS Forefathers’ Society, which adopted many of its ideas from the Thule Society.

The SS-Ahnenerbe was involved in the mapping of different racial groups. Its members believed that they could classify races into two types: those with Aryan elements in their blood, and those without any Aryan heritage. The latter were to be eliminated. These ideas were the impetus behind both the Holocaust and the Schaefer mission to Lhasa in 1938-39. While the SS-Ahnenerbe society itself faded in prominence, Himmler supported its ideals, and he contributed funds when Schaefer proposed the Lhasa mission.

Schaefer’s interest in Tibet was academic, and it is doubtful that he really shared Himmler’s belief in the ideas of either the Thule Society or the SS-Ahnenerbe. Indeed, he told one British official in India, “I need the sympathy of highest officials in my country to raise funds and to get the money out for future exploration work.” But Schaefer was clearly willing to go along with the Nazi agenda in order to achieve his own ambitions, and he was a member of both the Nazi party and the SS. Included in the expedition, moreover, was at least one ardent proponent of Nazi racial ideology.

Bruno Beger believed that if a race had any Aryan heritage, then evidence could be found in the physical features of the race’s upper classes. Even before Schaefer’s mission was announced, Beger had proposed an expedition to map the characteristics of the peoples of eastern Tibet to ascertain whether they were originally Aryans. But Beger was no mere theorist. During the 1940s his research into the physical characteristics of Central Asian peoples was carried out using concentration camp victims, reportedly placed at his disposal on the orders of Gestapo chief Adolf Eichmann.

The Schaefer mission left Germany in April 1938. The fact that Schaefer himself had accidentally shot and killed his wife while hunting wild boar just six weeks earlier was not seen as reason to delay. The mission received considerable publicity, and the British governments in both London and Delhi were immediately worried about the German aims. The British ambassador in Berlin reported German newspapers as saying, “This large-scale expedition is under the patronage of Reich SS leader Himmler and will be carried out entirely on SS principles.”

Permission for the expedition to travel through British-held India to Lhasa was initially refused. At that time the British imperial Government of India cooperated with the Tibetan government in restricting the number of visitors to Tibet from India. However, the British were also following a policy of “appeasement” toward Hitler’s Germany in the hope of avoiding a major conflict in Europe. Therefore the imperial government bowed to pressure from London, and the British representative in Sikkim was told that it was “politically desirable to do anything possible to avoid any impression that we have put obstacles in Schaefer’s way.” A loophole was found to allow the expedition to continue. Diplomatic pressure kept the British from significantly interfering with the remainder of Schaefer’s mission.

One major problem the Schaefer mission encountered was its leader’s mental state, which had apparently been affected by his wife’s death. Schaefer seemed to transfer his attentions onto one of his Sikkimese servants, a young man referred to in the files as “Kaiser.” The British representative in Sikkim, noting that “Schaefer’s habit with his employees is to pay them well and beat them often,” concluded, “We are all inclined to think that the gentle Kaiser has some sort of special appeal for the dominant Schaefer.” When the German applied to take Kaiser back to Germany with him, permission was quickly refused, as the British feared that Kaiser would become a Nazi sympathizer. Upon reaching Lhasa, the Schaefer mission must have found influential friends in the Tibetan government, for they were able to extend their stay in Lhasa for several months. The British representative in Lhasa, Hugh Richardson, reported that Schaefer and his companions “created an unfavorable impression in Lhasa and by contrast heightened our prestige.” He reported that the Germans were stoned by monks at a festival when they used their camera too blatantly and that they had made themselves unpopular by acting against Buddhist principles in killing local wildlife and ill-treating servants.

Despite this, Schaefer was received by the Reting Regent, the virtual ruler of Tibet during the Dalai Lama’s minority. The Regent was persuaded to write to Adolf Hitler. In his letter, the Regent acknowledged German efforts to create a lasting empire of peace based on racial grounds. He assured Hitler that Tibet shared that aim, and agreed that there were no obstacles to peaceful relations between the two states. So if Schaefer’s mission was a diplomatic one, it was a reasonable success in terms of establishing high-level contacts with Tibet. But, of course, the Tibetans had no real concept of the actual strategies involved in the Nazis’ racial policies.

What the Schaefer mission did not find was any support for the wilder ideas of the Thule Society. The mission did not encounter any mystic masters, find any long-lost Aryan brothers, or obtain any secret powers with which to save Hitler’s Third Reich from ultimate defeat. Indeed, it is doubtful that Schaefer devoted much attention to searching for them. His party did not include any experts on Tibetan religion and must have realized that if the Tibetans had possessed any special powers that might be employed in world conquest, they would already have used them to protect themselves from the Younghusband mission that had marched to Lhasa in 1903-4.

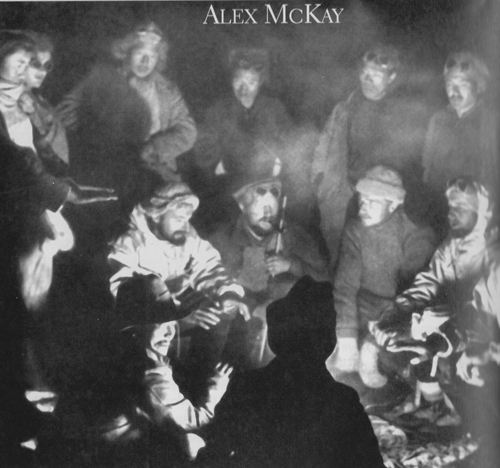

The Schaefer mission finally left Lhasa in May 1939. Returning via Sikkim and India, they arrived back in Germany in August of that year. Within weeks, World War II had begun, and although other missions to Tibet were proposed in wartime Germany, none of them were able to proceed. The Nazis’ direct links with Tibet were thus ended. Schaefer and his colleagues had returned to Germany with more than 2,000 biological and ethnographic specimens, 40,000 photographs, and 55,000 feet of movie film. During the war years they worked on this material, some of which was lost to Allied bombing. Schaefer published several books, which included probably the first full-color photographs of Tibet to be published. A commercial film was also produced and still survives. It includes a brief but chilling segment in which Beger can be seen measuring the skulls of Tibetan peasants. He may have been searching for heads that were “dolichecephalic” (long-headed), a sure sign of Nordic blood according to some Nazi theorists.

In 1942, Himmler ordered an increase in research into Central Asia, aimed toward helping the war effort. Sven Hedin, the great Swedish explorer of Central Asia and a Nazi sympathizer, agreed to lend his name to an institute in Munich where Schaefer, Beger, and others carried out their research. Part of the role of the Hedin Institute was also to offer the German people some escape from the war. Mythical and colorful aspects of Tibet were publicized, often with the implication that Tibet would provide Germany’s salvation. But while Schaefer played a major part in the establishment of the Hedin Institute, the extent to which he believed in the cause remains difficult to ascertain. Many of his statements seem to be little more than necessary rhetoric. Beger, however, who was later to be imprisoned for war crimes at the Nuremberg trials, remained a keen proponent of Nazi ideology.

Although all five members of the mission survived the war and lived on into the 1980s, the only books about their journey were published in German and are long out of print. Within nine months of their reaching Lhasa, Germany had invaded Poland and plunged Europe into World War II, and the expedition was almost forgotten.

In the mid-1990s, when the Dalai Lama hosted a reunion of Europeans who had traveled in pre-Communist Tibet, Beger, the last survivor of the mission, was among those who attended the gathering. When details of his enthusiastic Nazi past emerged, it proved a considerable embarrassment for the Tibetan government-in-exile.

The Nazis’ dreams about Tibet derived directly from the ideas of the Vril and Thule societies, which had constructed an image of Tibet based on fantasies of the type made famous by Madame Blavatsky, Lobsang Rampa, and other mythologizers of Shangri-La. Tibetan Buddhism appealed to the Nazis only inasmuch as its esoteric aspects offered them the promise of acquiring worldly power, just as the Japanese militarists were attracted to aspects of Zen Buddhism that could serve their interests. While their attempts to pervert the dharma ultimately failed, many of their ideas are still alive today. With the spread of Buddhism in the West and the dawn of the information age, however, the ability of hate groups to distort Buddhist symbols and ideas for their own purposes can hopefully become diminished.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.