One of the most puzzling aspects of the Buddha’s teachings is the idea of no self. If there’s no self, who gets angry, who falls in love, who makes effort, who has memories or gets reborn? What does it mean to say there is no self? Sometimes people are afraid of this idea, imagining themselves suddenly disappearing in a cloud of smoke, like a magician’s trick.

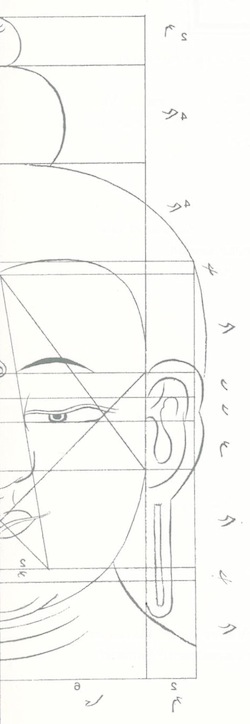

We can understand no-self in several ways. The Buddha described what we call “self” as a collection of aggregates—elements of mind and body—that function interdependently, creating the appearance of woman or man. We then identify with that image or appearance, taking it to be “I” or “mine,” imagining it to have some inherent self-existence. For example, we get up in the morning, look in the mirror, recognize the reflection, and think, “Yes, that’s me again.” We then add all kinds of concepts to this sense of self: I’m a woman or man, I’m a certain age, I’m a happy or unhappy person—the list goes on and on.

When we examine our experience, though, we see that there is not some core being to whom experience refers; rather it is simply “empty phenomena rolling on.” Experience is “empty” in the sense that there is no one behind the arising and changing phenomena to whom they happen. A rainbow is a good example of this. We go outside after a rainstorm and feel that moment of delight if a rainbow appears in the sky. Mostly, we simply enjoy the sight without investigating the real nature of what is happening. But when we look more deeply, it becomes clear that there is no “thing” called “rainbow” apart from the particular conditions of air and moisture and light.

Each one of us is like that rainbow—an appearance, a magical display, arising out of the various elements of mind and body. So when anger arises, or sorrow or love or joy, it is just anger angering, sorrow sorrowing, love loving, joy joying. Different feelings arise and pass, each simply expressing its own nature. The problem arises when we identify with these feelings, or thoughts, or sensations as being self or as belonging to “me”: I’m angry, I’m sad. By collapsing into the identification with these experiences, we contract energetically into a prison of self and separation.

As an experiment in awareness, the next time you feel identified with a strong emotion, or reaction, or judgment, leave the storyline and trace the physical sensation back to the energetic contraction, often felt at the heart center. It might be a sensation of tightness or pressure in the center of the chest. Then relax the heart, simply allowing the feelings and sensations to be there. Open to the space in which everything is happening. In that moment, the sense of separation disappears, and the union of lovingkindness and emptiness becomes clear. We see that there is no one there to be apart. As the Chinese poet Li Po wrote: “We sit together the mountain and me/ Until only the mountain remains.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.