Jerusalem Moonlight: An American Zen Teacher Walks the Path of His Ancestors

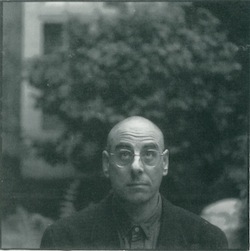

by Norman Fischer

Clear Glass Press: San Francisco, 1995.

190 pp., $16.00 (paper).

One morning, some six years ago, I saw Taizan Maezumi Roshi on one of his rare visits to New York. Maezumi Roshi, who died this past May, paid tribute to the practice of a senior monk at the Zen Community of New York, a woman who came from a religious Jewish household and who, after years of practice, was shortly to become a Zen teacher.

He said two things that morning: how much he appreciated the Judeo-Christian tradition that informed the religious background of almost all his students, and how much he appreciated the practice of certain students, and this monk in particular, who had undergone deep, often painful religious conflicts in the course of pursuing Zen practice as their religious path. I remembered that morning in reading Jerusalem Moonlight, by Norman Fischer, a Zen priest and the Abbot of Green Gulch Farm Zen Center in Marin County, California. For Fischer’s Zen path is a Jewish path as well, full of the contrasts, associations and even some of the ambivalences experienced by other Jewish Buddhist practitioners.

By his own account, Fischer was not raised in a traditional Jewish home. “I never doubted my own blood membership in the lineage,” he says in describing his personal sense of belonging to the Jewish people. But those roots were cultural and familial, rather than religious, and when he finally began his spiritual practice, it took him in the direction of Zen meditation and the priesthood rather than along the path of traditional Jewish observance. And yet, on his trip to Israel in 1987, he experienced a sense of coming home. Not a homecoming that evoked feelings of guilt or inadequacy (though with understated humor he describes his encounters with certain religious Jews and their definite views of Jews, like him, who choose different spiritual paths), but of appreciation – appreciation for a panoramic past, for a rich and colorful heritage, for parents and cousins, American Jews and Israeli Jews, for the multiple of threads that connect his life as a Zen teacher and priest to his Jewish origins.

While his descriptions of the current Israeli landscape—physical, sociological, and political—are of some interest, his profiles of the various Israelis he meets (long-lost Fischer cousins, Chasids, Yemenites, Bedouins, East Jerusalem merchants, tour guides and kibbutzniks) are positively delightful. They’re Yiddish-speaking, Hebrew-speaking, verbose, pushy, argumentative people with a life and death mission, a zeal fed by insecurity, and a gushing familiar warmth amplified by plenty of food and hospitality. There is arrogance and compassion, materialism and simplicity, and a nationalistic chauvinism slowly tempered by the passage of almost fifty years, including five wars, an Intifada, and uneasy peace talks with the Palestinians.

Best of all, Fischer alternates chapters on his visit to Israel with reveries on his life as a Zen teacher at Green Gulch, thoughts regarding his teacher, Richard Baker Roshi, and Baker’s prolonged exile from the San Francisco Zen Center, remembrances of the death of his mother in Florida (which prompted him to attend daily service at a nearby synagogue to say Kaddish), and even a humorous account of a celebration at Rinso-in temple in Yaizu, Japan, formerly the temple of Suzuki Roshi. He leapfrogs effortlessly among the various tapestries of his life, across several years, cultures, and even continents. There is no linear continuity, just an evocation of personal moments—loss, contentment, and occasional bewilderment—against the perplexing and unending story of the Jewish people, in Israel and out.

There is no attempt by Fischer to reconcile his Zen practice to his Jewishness. For Fischer, his Jewish roots and Jewish family are an integral, vital part of his life. Like the ceremonies as Rinso-in temple in Japan and his encounter with Thich Nhat Hanh, they nurture his teaching and practice. In Jerusalem Moonlight Judaism and Buddhism do not easily commingle, but the tension between them sparkles with buoyancy, celebrating this modern, mysterious intersection of two ancient traditions.

Eve Marko is a development consultant who specializes in not-for-profit organizations. She lives in West Hurley, New York.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.