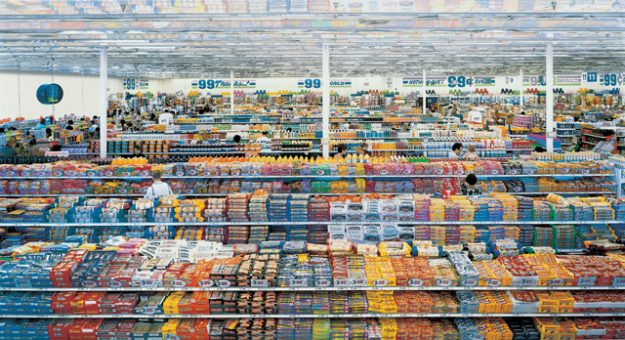

Working with dying people, I see many houses. After people die, their houses are left behind, often filled to the brim with things that they clearly felt they needed to have, like dozens of statues of lions, thousands of books, many cans of creamed corn, and so on. I’m not talking about hoarders, either—just folks. Humans are like magpies in that way, collecting shiny objects and other things that attract them. Seeing, wanting, grabbing—it seems to be innate. Something we can work with.

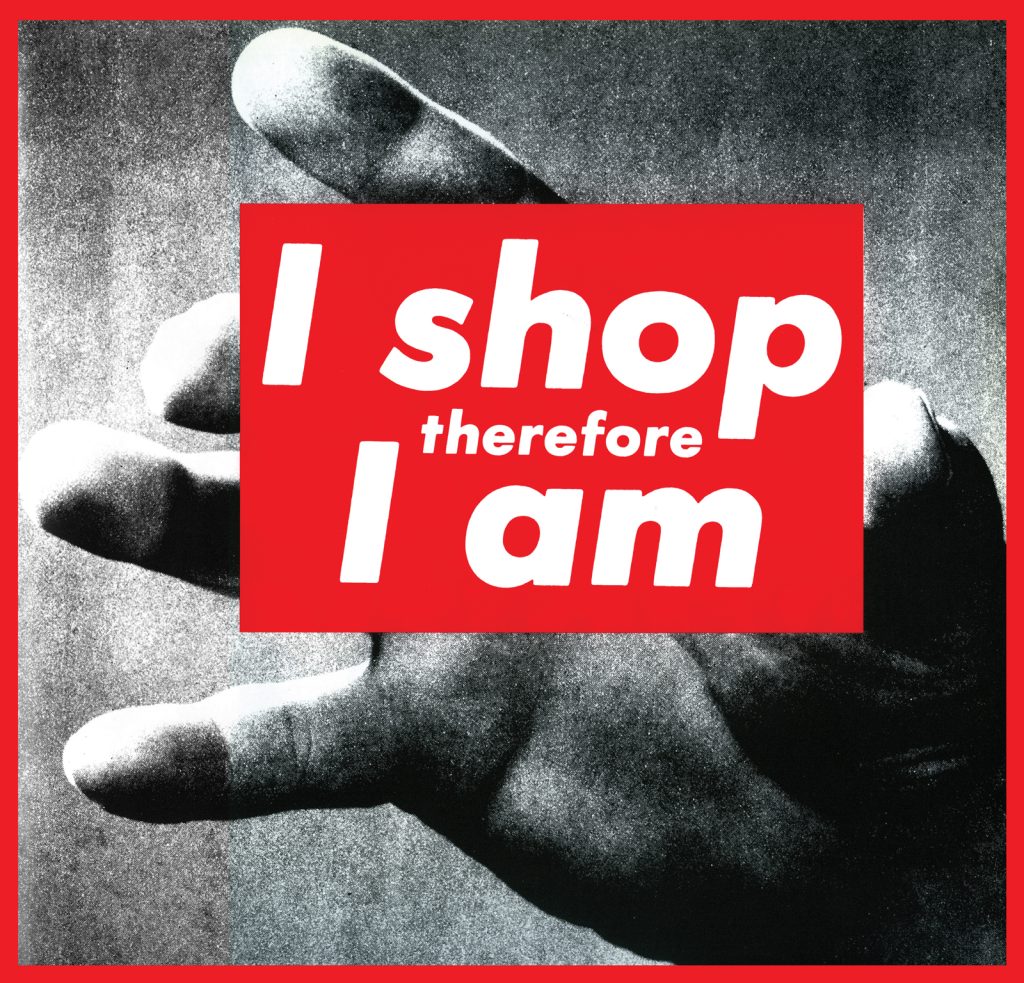

I have a very dear friend who has acid reflux. Two of the biggest triggers for his acid reflux are chocolate and gluten, and he knows this. But you should see him in front of a cake counter! He practically licks the glass from so much wanting, because he loves sweets. I understand that. It might seem silly, but I get like that about new iPhones. Whenever a new one comes out, I’m overcome with impulsive thoughts to buy it immediately. I want it now. Luckily for me, it seems like Apple comes out with a new version of the iPhone every other week, so I’ve had a lot of practice with riding the bucking bronco of desire. The cycle goes like this: I read that a new one is going to come out, and then I watch the little sneak preview video they do, and then I find myself going to the store . . . just to look at them. I might as well be salivating in front of a cake counter, too.

It’s been interesting to pause and see what’s driving all of this, which is usually a feeling of deficiency. Some kind of lack. And if I pause long enough, I realize that I’ve tricked myself into believing that somehow this new phone will fill in that lack. It’s not just a phone anymore; it represents so much more.

I was invited to the Hampton Classic horse show. Mercedes Benz was a sponsor, and they had the latest fully loaded Mercedes SUV out on the field. Some guy came up to the car and said—out loud—“I gotta have this car. My life is going to rock with it!” He got in the car, banged on the steering wheel, and said, “This is mine!” He handed someone a credit card and demanded, “Get me one of these, stat.” It was amazing to see this in action, because it was the living embodiment of how we all get swept away in our own minds. There’s nothing wrong with buying or enjoying a car, if you can afford it and all that. But thinking that some object is going to make us truly satisfied and allay our feelings of lack, longing, and dissatisfaction is nothing but a fantasy.

What would it be like to be truly content with what we have? You can understand that in regard to material things, of course, but I also mean it in regard to our life in total. What would it be like to walk down the street like that? Not imagining where you’re going or where you’re coming from but being content with whatever the street, the world, has to offer at exactly that moment in time.

Dogen said it would be like this: “The mind and the externals are just thus. The gate of liberation is open.” What? Let me explain.

At the Zen center we have a few beautiful tea bowls made by a Japanese potter, all of which are chipped now, because people wash them and stack them in the metal rack, and they’re very fragile. When I talk to our community members about not putting them in the rack, they say, “They’re too delicate to use. Why do we even have them?” Suzuki Roshi had the same problem with the teacups in his own Zen center. (It must be a Zen center epidemic.) A student complained to Suzuki about the cups. He smiled and said, “You just don’t know how to handle them. You have to adjust yourself to the environment, not vice versa.”

This is what Dogen was saying, too. The gate of liberation is always open. Liberation from what? Liberation from walking around in a dream, like a zombie looking for contentment outside your immediate and precious life. If only you could actually recognize and receive what is here in front of you, rather than what you wish were here instead. Why is that so hard? I don’t know, but I do know that I certainly have a tendency to want to adjust my environment to myself, not the other way around. Instead, is it possible for us to constantly give thanks for whatever our life gives us? This is how to practice being truly content with what we have—even when it seems impossible.

One of my heroes of practicing this radical contentment is the 18th-century haiku master Issa, who is a beloved poet in Japan. He has a haiku that goes “Everything I touch / with tenderness, alas, / pricks like a bramble.” Essentially, “Everything I touch turns to shit.” He had his reasons for saying so. His mother died when he was 3, and he was raised in part by a loving grandmother, who died when he was 14. He was sent away from his home by his father and stepmother, not returning until he was 49. He then met his wife, Kiku. Their first child died in birth. Their second died as a toddler. Then a third child died, and finally, Kiku herself died. It was after their second child’s death that Issa wrote probably his most famous poem: “This world— / Is a dewdrop world, / And yet, and yet . . .”

Issa was so interested in that “and yet.” In a body of work inspired by incredible suffering and melancholy, there is also that incredible sweetness of the “and yet,” which pervades his writing. It’s a sweetness that coexists with sorrow, and it reminds us that sweetness is always available to us, if we’re willing to fully enter our life, just as it is.

♦

From Wholehearted: Slow Down, Help Out, Wake Up, by Koshin Paley Ellison © June 2019. Reprinted with permission of Wisdom Publications.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.