Karmic Grace

The riddle of desire was poignantly unraveled in Joan Duncan Oliver’s essay, “A Drink and a Man” {Summer 2004}. The way she expressed herself brought me right into the experience of her “karmic grace”—when the excruciating pain of addiction and potential for liberation came together. Her essay revealed the essence of the dharma, and I hope to read more from her.

—Alix Engel, Palm Beach Gardens, Florida

The Problem with Puritans

James Baraz’s article {“Lighten Up!” Summer 2004} brought up some interesting points. It is true that sometimes American Buddhists approach practice with a heaviness that, if anything, only compounds suffering. Perhaps this is because they infuse their new spiritual practice with a Puritanical self-judgement that is foreign to Asian cultures, and certainly incompatible with Buddhist teachings. It makes perfect sense to sort this out and make clear that the Buddha was not advocating self-mortification but a Middle Way that meant not doing what was “good,” but doing what was most skillful in liberating us from suffering. As Baraz points out, there is nothing wrong with outward expressions of joy; and he rightly acknowledges that, in suppressing joy, he was simply indulging his own misguided notions of what was “spiritual.” But I don’t think this problem is so common that we need to make a big fuss about it.

It is far more common for us Western practitioners to take the other route: Whatever we find uncomfortable or disquieting in the teachings, we simply dismiss. Renunciation gets a particularly bad rap, leading many to tailor their Buddhism to their own particular tastes. Somehow we feel that the goal of enlightenment is possible without giving anything up. The result is the sort of rank sentimentality that seems to have overtaken the wedding ceremony Baraz presided over: Indeed, even in wishing others happiness, we give something up—our tendency to indulge our own jealousies. And yet from the article’s feel-good tone–down to the frolicking boy-monks in the accompanying art piece-we can only gather that with a little bit of love and fair-weathered metra meditation all will be well. Somewhere along the line, we seem to have lost the gritty challenge of renunciation—not the dour self-denial of the Puritan—but a renunciation that comes from the genuine aspiration to be free. In your special section on desire {in the same issue}, like Baraz, you seem to move in the direction of having it all (a notable exception is the excellent opener by Matthieu Ricard). For instance, it doesn’t seem to occur to Tara Brach for a moment that she might simply cut the desire at its root. Instead, she succumbs to a sentimentality that would have made her a welcome guest at the wedding Mr. Baraz describes.

Nevertheless, I remain a fond reader.

—John Hals, Dallas, Texas

Abuzz

Thanks for the great Summer 2004 issue. I think “Buddha Buzz,” by Jeff Wilson, is a fun feature in your magazine, and one item in the issue “Prayer Wheeling”—is particularly interesting. Where did this story come from? I would appreciate learning more about it.

—Ulla Zwicker, New York, New York

Jeff Wilson Responds

I, too, thought that the World Trade Center prayer wheels story was wonderful. It first came to my attention via an article written in January by Erik Baard for the Village Voice. If you go to www.villagevoice.com and search for “Wind and a Prayer,” you should find the original story in the archives. The website for Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill LLP, the designers of the Freedom Tower, is www.som.com.

Faulty Facts

In Allan Hunt Badiner’s “The Last Blissful Breath” (Summer 2004), the account of Kushinigar is charming, but the history is completely mangled. In the second column we find the author confidently asserting that “by the end of the fourteenth century, after Mogul invasions wiped Buddhism off the face of India, Kushinigar was pushed back into obscurity.”

Any student of Indian history would recognize a trainwreck of nonsense: The raids of northern India in the late twelfth century were decisive in the destruction of Gangetic plain monasteries; the Mughal dynasty began in 1526, not the fourteenth century; and Buddhism has existed continuously in the Kathmandu Valley from at least 464 C.E. up to the present day in South Asia. Modern state boundaries (of India, Nepal, and Pakistan) cannot be used to analyze the history of Buddhist culture in South Asia.

—Todd Lewis, Professor of World Religions, College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, Massachusetts

Sleeping Dog Awakened

I generally find Tricycle articles at least interesting and sometimes very instructive. “Our Man in Bodh Gaya” {Summer 2004} would have fallen into the “interesting” category if not for the insulting comment in the opening paragraph about the “court-appointed leader of the free world.”

If Mr. Magill wants to express his political opinions, he should use an appropriate forum. Presumably one is not banished from the ranks of Buddhist practitioners if one votes Republican. His remark has the smugness of one for whom there is only one correct opinion.

As to the substance of the matter: There are those who believe that the Florida Supreme Court had no right to change the rules because they didn’t like the result of the election. Florida’s legislature, empowered to do so by the U.S. Constitution, laid out exactly what should take place in the event of a close race. The state election officials followed those rules. The Florida Supreme Court determined that the result was not “fair” and decided that they had the right to make up their own rules. The U.S. Supreme Court, rightly, said that no, the Florida Court has no right under the Florida or U.S. constitutions to arbitrarily rewrite election law, especially after the election has taken place. Incidentally, several south Florida newspapers conducted their own “recount” in the months following the election. Lo and behold, they found the result did not change.

So if Mr. Magill wants to be a Bushhater, that is his privilege. But don’t give us this c**p about “court-appointed.” Anyway, what does this political warfare have to do with Buddhism?

—Jerry Cohn, Haverhill, Massachusetts

Blessings Behind Bars

Thank you for your special section on prison and the dharma {Spring 2004}. I was fortunate enough to be introduced to Buddhism and yoga before I came to prison, and they have truly been my paradise amid this hellish samsara of loss and pain. I am in a women’s federal prison, and we have a small group of practicing meditators. We are blessed with a chaplain who honors our practice and who has recently gotten us sitting cushions and a Buddha shrine (a big, heavy Buddha, incense, and a gong).

I was pleased that the interview with Fleet Maull addressed the issue of prison reform because many people are needlessly imprisoned or sentenced to ridiculous amounts of time. The helplessness and suffering in prison is so great that many of us rarely find peace except during our practice. I encourage the Buddhist community to further its outreach for both the spiritual assistance and political activism that helps bring an end to needless suffering.

—Kirsten Erkfritz, Federal Medical Center, Carswell, Fort Worth, Texas

Perverting the Precepts?

In the Letters section of the Summer 2004 issue, I was shocked to find Michael Sweet of Madison, Wisconsin, objecting to the content of Geri Larkin’s “On Practice” piece in the Spring 2004 issue. Mr. Sweet truly believes that the “injunction to sexual exclusivity has no basis in any Buddhist tradition.” To the contrary, this concept finds its basis in all Buddhist traditions. If Mr. Sweet is a practicing Buddhist of any tradition, and has taken the refuge vows and the five lay precepts, and still believes that there is room in practice of the dharma for our “polymorphously perverse primate natures,” I would like to suggest that he return to his teacher to have the precepts explained in greater detail. Or perhaps he feels that the third precept, “Refrain from sexual misconduct,” does not apply to promiscuity.

In taking this precept as a primary mindfulness point for lay practice, the practitioper is of course meant to understand that sexual conduct is to be undertaken mindfully and compassionately. When I was given this precept, my own teacher explained very clearly that the intent of the precept is that sexual conduct should only occur between two consenting individuals within the commitment of a monogamous relationship.

Perhaps the only point of Mr. Sweet’s that is more disconcerting than his seeming lack of understanding of this precept is his overtly expressed belief that sexual “dalliances” can be seen to be in line with the Buddhist concept of nonattachment. If he truly believes this, I would encourage him to take a copy of his letter to his teacher and spend many rounds of meditation contemplating the compassion and mindfulness cultivated by the precept to refrain from sexual misconduct and the enormous harm that can be created when this precept is ignored. I would be truly frightened to hear his interpretation of the first precept, “Refrain from taking life.”

—Acharya Khamsa Steven KinCannon, Director and Guiding Teacher, The Householder Dharma Project

Who Needs a Fancy Cushion?

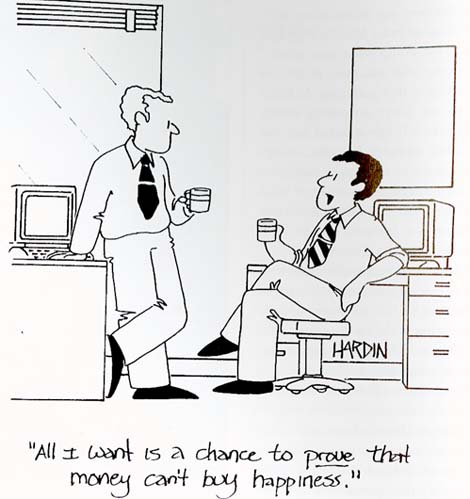

Thanks for another fine issue of Tricycle. When I look at the advertisements for meditation paraphernalia, I am reminded of the boy who complained to his father that he had nothing to do. The father said, “Why don’t you go out and play baseball?” The boy replied, “I can’t. There’s no Little League here.”

—Robert Olson, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Sentient Soybeans?

While your Winter 2003 issue had many excellent and provocative articles, I found “The Buckshot Bodhisattva” to be extremely disturbing. The fact that a leading Buddhist journal would print such an article is an illustration of the depths to which Buddhism has fallen in the United States in its failure to be an effective voice for those sentient beings we call animals. In that article, you merely reflected the current cultural atmosphere and failed to question it. Then, in the letters section of the following issue (Spring 2004), you gave Michael Soule yet another opportunity to spread misinformation and harden readers’ hearts toward the suffering we humans routinely inflict on animals.

Contemporary American culture virtually completely dominates animals, seeing them as commodities to be genetically manipulated, confined, killed, sold, eaten, worn, used for our entertainment, and subjected to vivisection. Where are the Buddhist voices speaking up for the billions of animals terrorized and brutalized in this country every year? I’ve seen precious little on this in Buddhist writings and periodicals, and yet this should be a matter of pressing concern for all Buddhists. Instead, your magazine goes the other way and glorifies a fellow who, in your words, “finds the dharma, opens his heart, and goes hunting.”

Hunting is killing and turns a human being into a predator, which is the antithesis of the bodhisattva ideal and of the dharma itself. As long as we eat animal products, we will inevitably see animals as commodities to be eaten, and by extension, to be hunted and used. According to the dharma, sentient beings are not commodities. By treating them as such, we sow seeds of violence in our lives that invariably come back to haunt us. As Buddhists, we should be helping to raise consciousness in our culture so that beings-all beings-are respected as beings and treated with kindness, and not seen and treated as mere objects. Ahimsa, nonharming, a core teaching of Buddhism, is sadly neglected in American Buddhism, and this whole affair is a telling manifestation of that fact.

—Will Tuttle, Ph.D., Healdsburg, California

I find it interesting to read the controversy developing over Soule’s hunting article. The first law of our existence on this planet, perhaps a universal one, is that we must kill to live. To be critical of one being’s choice of how to accomplish this is to misunderstand one of the basic principles of our lives. We are all predators, and life is violent and cruel. It is a human concept that we differentiate between various forms of life and construct opinions as to what is morally acceptable. The life in a soybean is as valid and sacred as the life in a deer or a human.

—Rick Klepfer, Cushing, Maine

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.