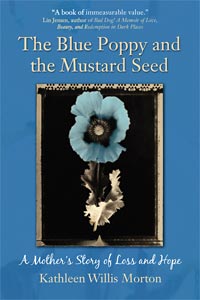

The Blue Poppy and The Mustard Seed: A Mother’s Story of Loss and Hope

Kathleen Willis Morton

Somerville, Mass: Wisdom Publications, 2008

175 pp., $15.95 paper

THE DEATH of a child, it’s said, is a loss from which parents never recover. It’s a tragedy so universally feared that those who lose a son or daughter may find themselves, as Kathleen Willis Morton did, in “an unnamed, and mostly unvoiced, situation of despair.” Morton’s eloquent new memoir, The Blue Poppy and the Mustard Seed, aims to break that silence. In giving voice to the story of her infant son’s life and death, and her subsequent search for meaning, Morton provides a map of the complex topography of love and grief.

A practicing Buddhist in the Tibetan tradition since age 17, Morton begins her memoir with a spare, shattering account of the death of her 45-day-old son, Liam, who was born with extensive brain damage. The “almost seven weeks” she and her husband, Chris, spent with their son were characterized by unexpected tranquility; knowing their time with him was short, they learned to live with contradiction, loving “unstrained and easily… without discernment.” Afterward, as they faced the reality of “having to go on living, which is no small matter, and move on, through the chaos in here and out there,” horror and overwhelming grief set in. Although The Blue Poppy and the Mustard Seed is immersed in the subjects of death, memory, and the passage of time, the book hinges on the question of the future: whether, and how, to move forward after such a loss.

Morton and her husband, both in their twenties, decide to leave their jobs and home and travel the world—not so much as an escape as a way to “make account of the days we lived…with Liam, waiting for the moment we’d have to let him go ahead, and to wonder together what life we would live next.” Morton weaves her ruminations on Liam’s life and death with vivid observations of Chinese teahouses, Tibetan sky burials, and Belgian battlefields, her wandering prose replicating the meanderings of her “mosaic, mending mind” in the midst of shattering loss. We learn only a few details of her life before Liam, and even Chris, who is always at her side, never emerges as a full-blown personality. Often, the world is blotted out by her sense of isolation and pain. When sensations do break through—a radish that tastes “like water and dirt,” a prostrating woman whose hands flare above her head “like the flames that gave way and righted themselves again inside the red rice-paper lanterns on her shrine”—Morton feels them deeply. Having left her old self behind, she begins to see with new eyes.

As Morton searches for an answer to her central question—“Why not give up if life is only suffering?”— Buddhism provides a framework for her grief. Like Kisa Gotami, the mourning mother sent by the Buddha to find a house untouched by death, Morton learns the univer- sality of loss. “It was my grief that pulled me down,” she reflects, “and my belief in Buddhism that pushed me back up again to look for the path that would release me from this suffering.” While belief alone can’t heal her, it offers the possibility of hope. The words of Buddhist teachers take on fresh urgency as she struggles to make sense of life in the wake of Liam’s death. Reflecting on Sogyal Rinpoche’s description of attachment as a fist clenched around a coin, Morton sees how her grief, clutched tight around the memory of her son, “leaves little room to feel anything else.” Still, life is persistent: almost every day, a busy market or weathered face draws her out of herself.

A storyteller by nature, Morton creates a new vocabulary of metaphors and symbols to help her learn to read the world again. Liam is the Tibetan blue poppy of the title—“sublime and rare,” with “profound, solemn blue” petals and yellow stamens; “a bright, happy contrast…like joy and sorrow.” She notices this contrast everywhere: in brutally oppressed Lhasa, a carefree tourist expressing delight; a photography exhibit in Prague that shows a woman whose face had been burned by acid beaming for the camera. Slowly, Morton grasps the truth set out in the Vimalakirti Sutra: “Samsara and Nirvana are not two.”

“Sorrow is a sacred blessing, a piercing awl,” she writes. “Through that puncture wound we can choose to see only the loss, what is not there, or look at the opening it has made in us, the spaciousness to be filled up with natural great delight if we are receptive and patient.” She dares to believe that she can learn from Liam, grieving without denying joy, accepting both light and dark. Inspired by the legend of the goddess Harati, who experienced the temporary loss of a beloved child before she became the protector of all children, Morton can even envision a future worth living.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.