In Buddhism, the standard phrase to refer to the transition of becoming a monastic is “to go forth from home into homelessness.” The Pali term for “going forth,” pabbajja, is now also used to mean a monastic candidate’s first ordination by which one becomes a novice monk (samanera) or nun (samaneri). From there, a candidate can pursue higher ordination as a fully ordained monk (bhikkhu) or nun (bhikkhuni), one who follows the full extent of the Vinaya, the Buddhist monastic code.

But for almost a thousand years, ever since the female monastic order died out, women in the Theravada tradition of Buddhism have been barred from receiving full ordination, caught without the first case of a circular cause: the Vinaya states that a bhikkhuni must be ordained by both bhikkhu and bhikkhuni sangha in order for the ordination to be valid. Although many Buddhist scholars and preeminent teachers now recognize the legitimacy of bhikkhuni ordination, which has been reclaimed through the Mahayana tradition, there are still those who protest or reject their standing as fully ordained nuns. Because of this, those women who have sought full ordination run the risk of finding themselves on their own, outside of a lineage and the established networks of support available to male monastics.

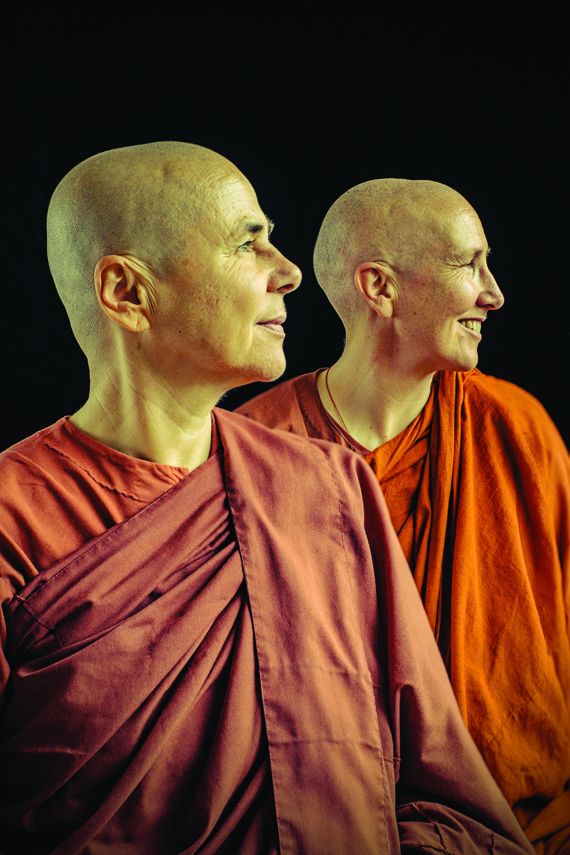

Such was the case for Ayya Santacitta and Ayya Anandabodhi, who together run Aloka Vihara, a rural training monastery for nuns in northeast California. They have gone “from home into homelessness” not once but twice: after 20 years as novice nuns, they left Ajahn Chah’s Thai forest lineage and pursued a more empowered but uncertain future. In 2011, upon their move from England to California’s Bay Area, they were fully ordained as bhikkunis by Ayya Tathaaloka Theri. “It was a big risk, and a huge step into the unknown,” says Ayya Anandabodhi of their stepping out. “But there was no question that that was what had to happen.”

The two bhikkhunis are supported in their mission to give other women the opportunity to live as fully ordained monastics by the Saranaloka Foundation, a nonprofit organization established in 2005 by lay practitioners in the United States. And though there is still much work to be done in equalizing women’s standing in the Buddhist traditions, the sisters of Aloka Vihara feel that we are now in a time of resurgence of the female monastic community. “New information is coming to light,” Ayya Anandabodhi says. “And old traditions are being questioned.”

—Emma Varvaloucas, Executive Editor

How were you each introduced to Buddhism, and why did you decide to enter the monastic community?

Ayya Anandabodhi: I was motivated to learn to meditate when I was 14, because I was experiencing a lot of suffering in my life, or—you could say— in my mind, and I had an intuition that meditation could help. During my search for a way to learn meditation, I came across the core teaching on the four noble truths, which point to suffering and its cause, along with its end and the path that leads to its end. That teaching touched me very deeply, the fact that the Buddha was acknowledging the suffering that we all experience but that generally the world doesn’t really acknowledge. It gave me a sense of self-empowerment rather than one of having to wait for some external source to support me.

When I first heard about the monastic life, I was 20 years old. I knew that there had to be monastics in the Buddha’s time, but I didn’t know that there was a living lineage. So as soon I heard about the monks in Thailand, I knew that was what I wanted to do with my life. My life very easily went off the rails, and I had strong self-destructive tendencies; I didn’t really know how to live in a skillful way. I felt that using monasticism as a framework in which to live would really guide me in the right direction and give me community.

Of course, when I first heard about the monks, I just assumed that there were also nuns. It didn’t occur to me that there might be any problem there.

Related: Bhikkhuni Ordination: Buddhism’s Glass Ceiling

Ayya Santacitta: My mother passed away very suddenly when I was 28. After that loss I felt very in need of somebody to help me to understand what it’s all about—living as a human being and all of that. A year later I went to Thailand to conduct research as a cultural anthropologist, and by coincidence I visited a monastery in the south of Thailand where there was a meditation retreat scheduled to start in three days, led by the very famous monk Ajahn Buddhadasa. Of course I had no idea who he was. But when I met him I got a deep sense of recognition that this was something for me. He had a strength, an unshakability of the heart that he transmitted with his being. I wanted to have that too, because my life was shaking all over the place. It became clear to me that I wanted to be like him, that I wanted to know what he knew.

I lived in Thailand for several years, returning to the monastery a few times, and I began to feel an increasing call toward the monastic life, which really confused me. I wasn’t ready for that at all at that time. And really, I thought that becoming a nun was a crazy thing to do. But I could not forget about that strong pull. And then three or four years after my first meeting with Ajahn Buddhadasa, I ended up in that monastery. I lived there for one and a half years as an upasika, a lay renunciant, before going to Amaravati Monastery in England, where I met Ayya Anandabodhi and became an anagarika, an eight-precept nun.

Did you ever have any doubts about diving into such a full commitment?

AA: I can’t say that I had any doubts. But I would say that the most challenging thing was to leave my partner. At the time I was in love with a man who had actually introduced me to the monastic sangha and to meditation, and I left him to become a nun at 24. It was very challenging to be celibate as a young woman who had literally just stepped out of a relationship and into the monastery. I had a lot of passion, and I had to find ways to channel that: I worked hard and channeled devotion to the Buddha.

AS: For me, the most difficult thing to give up was also intimate relationships. That’s a very deep human yearning that is inbuilt as part of having a human body, and I’ve had to grapple with that for over 20 years of ordination. Letting go of beautification— beautiful clothes and the like—was also a bit difficult, and there were points where it was grating to me. But I have been able to use the tools of the monastic life to work with the longing and put it through the fire of the transformation process. It’s not always easy, but it has obviously worked, because otherwise I wouldn’t still be here.

In the beginning, in the honeymoon phase, the path looks much easier than it actually is. But we have to keep staying with it, and the monastic form is a very good support to do that, no matter how rocky the road is going to become. If you use the monastic form in the right way, it’s not to suppress anything, but to stabilize yourself so you can take the punches better.

Do you think there’s a danger for people to use monasticism as a tool for suppression?

AS: I think there is a danger that we get too kind of fascinated by the tradition and want to become Asian. I was married to a Thai, I spoke the language and everything, and I thought I wanted to become like them. But after 20 years of being on the path, it’s very clear to me that this is not the way. Doing that is just reconditioning yourself. The path is deconditioning, deconstructing, and if you hang in long enough these cultural trappings are going to fall away from you.

Speaking of cultural trappings, you were both novice nuns in Ajahn Chah’s Thai forest lineage for almost 20 years before you decided to take leave of it. What were your reasons for doing so?

AA: As I mentioned, when I first heard about the monastic sangha it didn’t occur to me that there might be any problem to enter as a woman. I grew up in the UK, where we learned about equal opportunities at school. And even though there was still sexism here and there, there was also a basic sense that as a woman you can do what you want to do. So I was surprised when I came into the monastic life. It took me some time to really register how big the discrepancy was between the men and the women within the ordained sangha. At first, it didn’t look so bad because everybody is wearing the robes, everybody has a shaved head, everybody has the same access to the requisite food, medicine, shelter, and clothing, and the same access to the teachings. So it looked for a while as though the hierarchical system was just a conventional form, while for the purposes of real daily life, we all have the same access to everything.

But then over the years what became really clear was that to be women in a system where your ordination isn’t recognized is to occupy a very ambiguous position. We were siladharas, an order of Theravada Buddhist nuns created by Ajahn Sumedho, Ajahn Sucitto, and the first nuns in that lineage, but our actual ordination was contested. Some would say we were ordained, some people would say we weren’t. Some would say we were novices. Some would say that we weren’t even novices, that we were only lay renunciants. It became very undermining to live under that day in and day out. It was difficult to find one’s strength and confidence within that.

Ayya Santacitta and I both saw the need for a place where women could live and train and grow within their own context, where they’re not always in a relationship to a patriarchal system, a hierarchy where the men are always senior to the women just by the fact that they’re men. So the original idea was to start a branch monastery for nuns in the United States that would be within the siladhara form, staying in the Thai forest lineage. But within six months of being in the States, it became really clear that we were not going to be able to do that.

Why not?

AS: There were already other women here in California who were bhikkhunis, fully ordained nuns, and we didn’t want to jeopardize their efforts. Plus it was clear that the women on the West Coast wanted to have full opportunity. You can’t just talk them into thinking that a partial form of ordination is enough. It’s the full bhikkuni ordination that they want, the full legacy that the Buddha offered to women over 2,500 years ago. We just couldn’t stand up anymore and say that the siladhara form was enough. So we said, “OK, let’s step out.”

It’s not that we left the lineage because we necessarily wanted to leave the individual people. We had to leave the system because it was unwilling to part ways from Thai tradition. And we didn’t want to wait another 20 years until things might transform.

AA: For myself, the decision to leave the lineage and take full ordination was as clear as my decision to take the robes in the first place, even though it was a big risk and a huge step into the unknown. The Saranaloka Foundation had invited us to the United States specifically to create the branch monastery of siladharas; we didn’t know whether they would continue to support us now that we were leaving the lineage. That community had been central to my life since I was 22—the whole of my adult life, really—and it wasn’t easy to leave it. But at the same time there was no question that that was what had to happen.

Related: Are We There Yet?

Tell me about your current work to create a rural training monastery for women in northern California.

AA: We were in San Francisco for four and a half years, but at the end of May we moved to a beautiful rural setting in the Sierra Foothills, near Placerville. We both breathed a big sigh of relief to be back in the forest again—we are forest nuns, after all!

In San Francisco we didn’t have the space for people to stay over; there was only room for the monastic community, which was three nuns (including us) and one lay steward who helped with handling money and cooking and so on. Now, because there’s more accommodation space and because the environment is quiet and supportive for practice, we’ve started to attract women who are interested in living the monastic life. So there’s Ayya Santacitta and I, who are both bhikkhunis, and Ayya Jayati, who took full ordination this month. We also have Marina, our vihara manager, and one aspirant living with us currently, and more women are booked to come later this year who have expressed a serious intention to investigate the possibility of monastic life. So it’s been a huge step in the right direction to move out here.

What have been the effects upon your practice, either beneficial or detrimental, of no longer belonging to the lineage of a contemporary master?

AS: Many. From time to time, it brings up a lot of what I call the afflictive emotions like fear and doubt and grief. But at other times it brings up a lot of joy, the feeling that “yes, this is what I always wanted to do.”

There’s a lot of demand on us to stretch beyond our limits every day, because we are a small community. We offer teaching. We run a vihara. We do administration. We do building work maintenance, training people, welcoming guests. We are completely immersed in service now, whereas before as junior nuns we were in a more protected situation, with less responsibility. But the vision of what we want to offer other women keeps us going.

AA: The strongest connection I’ve had to lineage is through the Buddha, and certainly we haven’t lost that connection. Also, since taking full ordination I feel a much stronger alignment with the lineage of the bhikkhuni sangha, which I didn’t feel so much as a siladhara. Before, it was like the bhikkhuni sangha was this historical thing that had died out a long time ago. Now I really feel a tangible connection to the bhikkhuni lineage wherever it is around the world—in India, Sri Lanka, China, Taiwan, Korea—and going all the way back to the founder of the order, Mahapajapati, the Buddha’s adoptive mother and aunt.

On our main shrine we have an image of the Buddha and one of Mahapajapati. Those are my lineage holders.

And you’ve also had each other throughout this whole process—you met over 20 years ago, in 1992. What has it been like to embark upon the project of building Aloka Vihara together, and to be nuns together all these years?

AS: Ayya Anandabodhi doesn’t like it when I say this, but it was like an arranged marriage. We wouldn’t have chosen to work together for so long—we have always been friends, but we’re very different characters. It took us a long time to get used to working together because we have such different styles of doing things. Luckily, people mention that they like the combination of the two of us, because together we cover quite a broad spectrum of skills.

Every good quality has a shadow side as well, and the shadow of my good qualities is counterbalanced by Ayya Anandabodhi’s strengths. I can be pushy, very energetic, and she’s more grounded and steady. She helps me to slow down and see the qualities that I have to develop more. I’m not here to have fun, even if sometimes we do have fun; I’m here in order to grow and to be able to benefit myself and others by living this lifestyle. So in that sense we’re a great duo, because we don’t dilute each other by saying, “It’s all right, just keep going and indulge your preferences.”

How would you advise female practitioners, especially monastics or those interested in becoming monastics, to approach a tradition that is tremendously meaningful for them but that simultaneously has very outdated positions with respect to women?

AA: I think every woman has to find her own way. There are some excellent scholars around now who are studying the early Buddhist teachings and unearthing things like the fact that the eight garudhammas [the eight additional rules that nuns, but not monks, must follow] were a later addition and probably not the Buddha’s words. There has been a tradition for a long time in the Theravada lineage that women can’t take full ordination, but over the past 20 years that has slowly started to be overturned. It’s a time of . . .

AS: Clarification.

AA: Yes, clarification, and resurgence, a time when new information is coming to light and old traditions are being questioned. If you have a real calling to monastic life, search around. Go to a few different places and see what resonates for you as a spiritual practitioner and as a person. Stay at each place awhile and see what happens. But I should mention that monastic life is not an escape from the world. You’ll meet all your ghosts, you’ll go to all the places that are challenging for you, and if you’re going to join the bhikkhuni order in the Theravada tradition at this time, you have to enter with your eyes open, because it’s a pioneering time.

I hear people say that they want it to be like the monks, well established with a lineage behind it and lots of support. We’re not there yet. The bhikkhuni order is reemerging, and it takes a lot of generosity, dedication, commitment, and faith—in the sense of a deep, heartfelt conviction—to live this life. It is a challenging path. But I wouldn’t want to live any other way.

You just mentioned that there’s a lot of new scholarship emerging about the bhikkhuni order. Many know about the Buddha’s famous response to Mahapajapati’s request to create an order of nuns—he refused twice, and when he capitulated, he told her that the creation of that order would halve the life of the dharma—but not as many know about the parts of the scriptures where the Buddha speaks very positively in support of the existence of a bhikkhuni order.

AA: Yes, it’s an ongoing discussion. There are those who like to take the position that Buddha never wanted women in the first place, and there are those who point out that he actually said in the Digha Nikaya that he would not leave this earth until the fourfold assembly of bhikkhus, bhikkhunis, laywomen, and laymen were fully established. In my view, to have a fully enlightened Buddha who is a misogynist doesn’t add up.

There is a very interesting article by Ven. Analayo Bhikkhu in the Journal of Buddhist Ethics, “Mahapajapati’s Going Forth in the Madhyama-agama,” where he compares the Pali scriptures that were written down in Sri Lanka, which contain that particular sutta that is often quoted about the nun’s order halving the life of the dharma, with the scriptures that were written down at the same time in China. He’s found that in these Chinese scriptures— which, I should mention, are not Mahayana texts—there’s a line that says “Wait, wait, Gotami [Maha-pajapati], do not have this thought, that in this right teaching and discipline women leave the household out of faith, becoming homeless to train in the path. Gotami, you shave off your hair like this, put on the ochre robes and for your whole life practice the pure holy life.”

So it appears from this scripture that the Buddha is not saying women shouldn’t ordain; he’s saying to the women who were living in India 2,500 years ago, when women were still the property of men, “Don’t go walking out in the wild the way that the men do, because you’ll be vulnerable to attack, vulnerable to rape.” Ven. Analayo is proposing the possibility that the meaning could be “Then your life as a nun would be halved.” It makes much more sense to me that the Buddha would be compassionate and concerned for the welfare of women, concerned that if women were to wander in the way that men did, that they would be in danger. He was asking them not to do that, to instead practice at home and in safety.

If that’s true, it would certainly bring relief to a lot of female Buddhists.

AS: It’s important to remember that the teachings were written down several hundreds of years after the Buddha’s passing by Brahmans [priests] who were aligned with the misogynistic worldview of their time. So of course that worldview flew into the records.

AA: The one thing I always come back to is that compassion and wisdom are at the heart of the Buddha’s teaching. If you cannot find either wisdom or compassion in something, then I don’t feel that it can really be the Buddha’s teaching.

In the Western Buddhist tradition, as it has developed thus far, there hasn’t been a lot of emphasis on monasticism; rather, what is emphasized is how to fit practice into the daily life of a layperson. Can you speak about the importance of keeping the Buddhist monastic tradition alive in the West?

AS: When I entered the monastery I was very much in need of guidance, and having the setup in the monastery with senior nuns and monks, and the schedule and prescribed procedures and so on—it was a safe haven. It made me stop and take stock of my life, and turn my awareness toward myself rather than always going on to the next thing. It was a precious opportunity, and I’d like to make it available to others because I’ve benefited so much from it. It’s very simple: it’s worked for me, and I’d like to adapt it to contemporary Western needs and pass it on.

AA: I think it’s interesting that the question comes up as if the monastic tradition could be wiped out. What I experienced in myself was an inner awakening, a really strong calling to renounce. It was almost as though I had no choice. There are people just like me who have this calling, who want to live in a way where the whole orientation of your life is different. And as long as people want to do that there will be monasteries.

I’m constantly amazed since coming to the United States that just the way we live our lives as nuns—sometimes we go out and teach, but also simply our living according to the precepts, and wearing the robes and living on alms—touches something in people’s hearts. We’ve just moved to this small town in the foothills of the Sierras where we don’t know anyone, and what I find again and again is that people appreciate that we’ve come to where they are, and they feel that we can offer something. There are people who say, “Just to know that you’re there doing that is a support to my practice,” or “Just to know that at this time of day the nuns are gathering to meditate together is a support to my practice.” So the monastic life will never be mainstream, but as I see it, it’s a very important part of society because of how it ripples out and uplifts other people.

AS: I’d like to add, though, that we are not coming from a viewpoint that thinks the monastic life is superior to another lifestyle. It’s one lifestyle you can choose; it works for some, and it doesn’t work for others. I can’t be a prima ballerina, because I don’t have the proper equipment in my body. It just wouldn’t work for me. So if you’re not a monastic, there’s no value judgment. It’s just what it is.

It’s there if it’s for you, and if it’s not for you, then—

AS: Then do something else. There are so many things that need to be done.

Experience the nuns’ teachings firsthand in this month’s retreat, “Never Turn Away: Opening the Mind of Awakening,” a four-part series on how to overcome our habits of mind.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.