When Mayumi Oda is ready to create a new work, the first thing she typically does is meditate or chant. She often offers prayers to the goddesses—Tara, Sarasvati, and Kannon—who have been an inspiration to her as a Zen Buddhist teacher, an activist for a nuclear-free world, and a prolific artist whose unique style has earned her international acclaim as the “Matisse of Japan.”

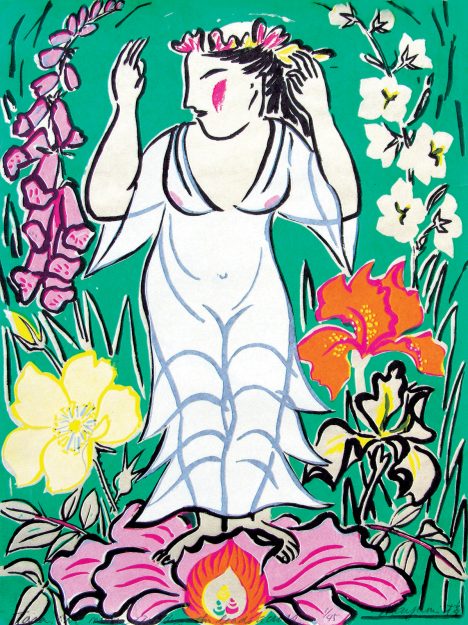

Born in the Tokyo suburb of Kyodo in 1941, Oda has had a unique connection to goddesses ever since her childhood. As a young girl she loved venturing out of her hometown to visit Kamakura, where Nichiren Buddhism (which her family practiced) took root in Japan. She would frequent a cave shrine dedicated to Sarasvati, and on one such visit, she encountered a seer who imparted the fateful words: “Young girl, you are going to be a successful painter,” Oda recalled in her 2020 autobiography, Sarasvati’s Gift. The seer was certainly right: Oda, now residing in Hawaii at the age of 80, has exhibited in solo shows and permanent collections around the world.

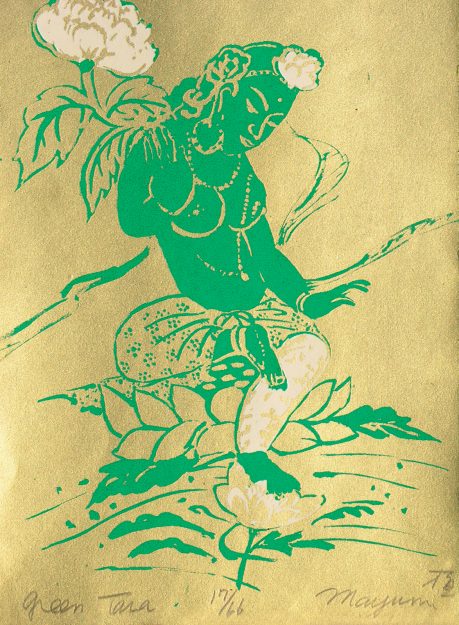

In 1966, Oda moved to New York City and began producing the brilliantly colorful goddesses that are now essential to her style and portfolio. “Through my creative process, I have been creating myself,” Oda says in her artist statement. “Goddesses are a projection of myself and who I want to be.”

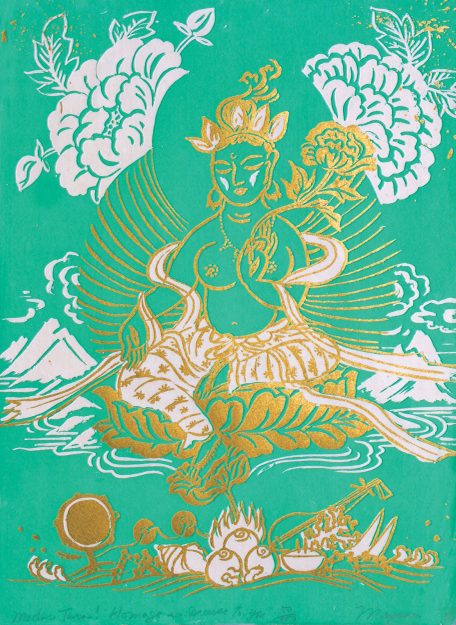

Although Tara has not featured as prominently in Oda’s life and art as the goddesses she grew up with in Japan, the Tibetan Buddhist bodhisattva with 21 forms has been a significant presence for her. “They’re the same—Sarasvati and Tara,” she told Tricycle. “They’re all goddesses that teach us compassion and love. I don’t have a favorite.”

Tara, known as the “Mother of Liberation,” speaks to Oda’s reverence for motherhood. She views her career as an homage to the feminine energy of her own mother, who fostered her creativity. Her connection to this energy deepened after giving birth to her first son in 1967. “I had a good mother who really cared for me,” she said. “[Her love] is in my body. I can’t separate them. Mother is now me, even if she’s gone.”

“Through my creative process, I have been creating myself. Goddesses are a projection of myself and who I want to be.”

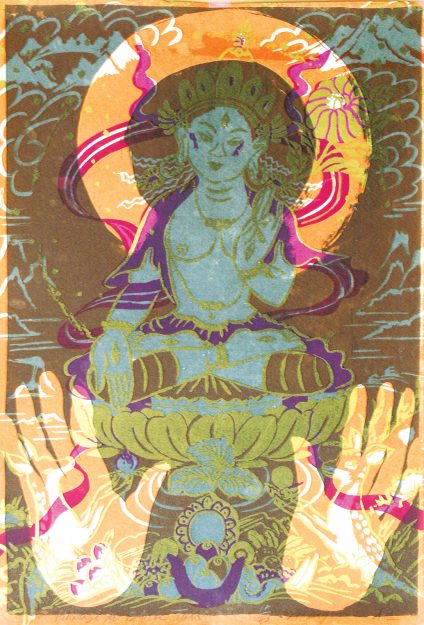

By invoking Tara’s mantra, Oda, much like Tibetan thangka painters, imbues her artwork with divine feminine qualities—wisdom, compassion, creativity, and reverence for nature—that are transmitted to the viewer. But she channels the goddesses in her own way, setting aside the strict proportions of the traditional Tibetan style in favor of her singularly fluid linework. She often reimagines Tara, such as a Black woman in Black Tara. In doing so, her goal is to create art that “feels real to me.”

“Green Tara is the goddess of the Earth, where all the living things rise and grow. Because I live on a farm and grow food, that’s real to me,” she explained.

“Silk screen lets you express the color freely. And my art is nothing but good color.”

In her silk screens, Oda can express herself more effortlessly, creating flowing lines that grace such works as Mother Tara! Homage & Praise to You.

“Silkscreen lets you express the color freely. And my art is nothing but good color,” she said. Working from such inner truths has also guided Oda’s activism.

“When you have compassion and you see something you have to do, you just do it,” she said. “The goddesses help me find that compassion. They give me love.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.