“Can technology set you free?” That was the question posed as the theme of a two-hour long “Battle of Ideas” by a British organization called, appropriately enough, the Institute of Ideas. The “Battle” failed to resolve the question, which should hardly have been surprising. The question has, in one form or another, been debated for centuries, and there was no reason to think it would be resolved on a chilly November evening in 21st-century London.

The event was held in 2012 at the Royal Academy of Engineering. The Academy’s website says its role is “to advance and promote excellence in engineering” and, in the following paragraph, claims its purpose is “to promote the United Kingdom’s role as a great place from which to do business.” The juxtaposition of that role and that purpose illustrates an important, and perhaps unintended, point: Technology doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and neither do debates about its merits. Both are the products of cultural, political, and economic forces.

The Institute for Idea’s question itself reflects an ancient ambivalence toward technology, one which has deep roots in human history. In Greek mythology, the theft of fire—a pivotal early technology—resulted in eternal punishment for Prometheus. The Greek gods punished human beings for similar acts of defiance or hubris. Icarus famously flew too high on wings of his father’s making. His death was as a punishment for his own presumption in attempting the flight, and for that of his father in creating this technology.

In the biblical story of the Tower of Babel, a new global community—the “whole earth,” in the words of Genesis—decides to “build a city, and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven.” This nearly completed engineering triumph disturbed God. “Now nothing will be restrained from them,” God says, “which they have imagined to do.” The Tower is promptly destroyed, while the universal human language—humanity’s “common platform”—is broken into thousands of tongues.

Thousands of years later, the deep suspicion of technology, rooted in both biblical and classical cultures, persisted. The view that even well-intentioned technology might violate God’s law is expressed, for example, in the Eastern European legend of the Golem of Prague, which first appeared in written form in the mid-19th century. As it happens, this was not long after the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which appeared with the subtitle A Modern Prometheus. And Shelley published Frankenstein just ten years after an early rendering of the Faust story, in which a science-minded protagonist “laid the Holy Scriptures behind the door and under the bench, refused to be called doctor of Theology, but preferred to be styled doctor of Medicine,” and in so doing made the prototypical “Faustian bargain.”

But for every ancient curse against technology, ancient literature has also provided us with imagery that seems to praise technology’s beauty and promise. In Revelation 21, the New Testament promises a New Jerusalem descending from the skies, “prepared as a bride adorned for…her husband.”

Her light was like unto a stone most precious, even like a jasper stone, clear as crystal;/and had a wall great and high, and had twelve gates, and at the gates twelve angels, and names written thereon, which are the names of the twelve tribes of the children of Israel./… And the building of the wall of it was of jasper: and the city was pure gold, like unto clear glass./And the foundations of the wall of the city were garnished with all manner of precious stones … /and the street of the city was pure gold, as it were transparent glass.

The beauty of this descriptive language is echoed in Buddhist works such as Pure Land Buddhism’s Daimuryojukyo, or Larger Infinite Life Sutra. Hisao Inagaki’s translation describes Sukhavati, or the “Western Land,” as follows:

[As] the breeze wafts … lotus-flowers of various jewels fill the land; each has a hundred thousand kotis of petals with lights of numerous colors—blue lotuses glow with a blue light, white ones with a white light, and, likewise, dark blue, yellow, red, and purple lotuses glow with lights of their respective colors … Each flower emits thirty-six hundred thousand kotis of rays of light, each sending forth thirty-six hundred thousand kotis of Buddhas … Each Buddha emits a hundred thousand rays of light and expounds the wonderful Dharma to beings in the ten quarters …

Residents of this land, says the sutra, “are masters of the supernatural powers. They are all of one form, without any difference.”

These ancient texts describe spiritual worlds, not human creations, and each resonates with levels of metaphor and meaning that have led to centuries of interpretation and reflection. It would be facile and disrespectful to portray them as mere technological fantasies. But they, like the dystopian passages quoted earlier, reflect human yearnings that are evident in our attitudes toward technology and our physical environment.

As technology has come to occupy an increasing role in our lives, it has come to occupy a larger place in our stories. And so has our ambivalence about it. The theme of technology as hubris can be found in countless tales from Frankenstein through H. G. Wells’s Island of Dr. Moreau to Arnold Schwarzenegger as the Terminator, and beyond. On the other hand, theStar Trek series or Steven Spielberg’s E.T. or Close Encounters of the Third Kind depict highly advanced technology as benevolent in its social effects.

Our mixed feelings about technology easily lead to simplistic thinking about its worth. So the Institute of Ideas was certainly right about one thing: We should be debating technology’s role in our lives.

Several years ago I spoke at a conference whose theme was “Transhumanism,” a loosely-defined movement that believes that humanity can and should merge with technology in a variety of ways, and for a variety of reasons. Transhumanists hope to upload their minds into computers, become human/machine “cyborg” hybrids, and extend their lifespans by centuries or even millennia. Later, at a dinner for the speakers, I was asked if I was a Transhumanist myself.

No, I said.

So you’re anti-Transhumanist?

No.

But radical new technologies will emerge, said my dinner companion, and probably in our lifetimes, that could change what it means to be human. When that happens, she asked, what will you do?

They were reasonable questions, even urgent ones. Technology has been changing humanity, and the planet, at an accelerating and sometimes dangerous pace. Transhumanists argue that human beings can enrich their lives by embracing, and literally merging with, their technology. Transhumanism’s polar opposite—the wholesale rejection of technology—can be found in the writings of thinkers like the 19th-century French anarchist Henry Zisly, who said “A bas la Civilisation! Vive la Nature!” (“Down with civilization! Up with nature!”) Zisly prefigured the modern “anarcho-primitivist” thought of figures like Wolfi Landstreicher (a pseudonym) and John Zerzan, who writes that “technology … is all the drudgery and toxicity required to produce and reproduce the stage of hyperalienation we languish in. It is the texture and the form of domination at any given stage of hierarchy and commodification.”

Transhumanists embrace technology, while anarcho-primitivists reject it. Neither should be marginalized, I would say, since they’re among the few who are actively participating in the critically important debate over technology’s role in the human future. But like it or not, we are all, whether active or passive, participants in the discussion, and this of course includes Buddhists. For Buddhists, as for anyone really, the key question concerns the values we bring to that conversation.

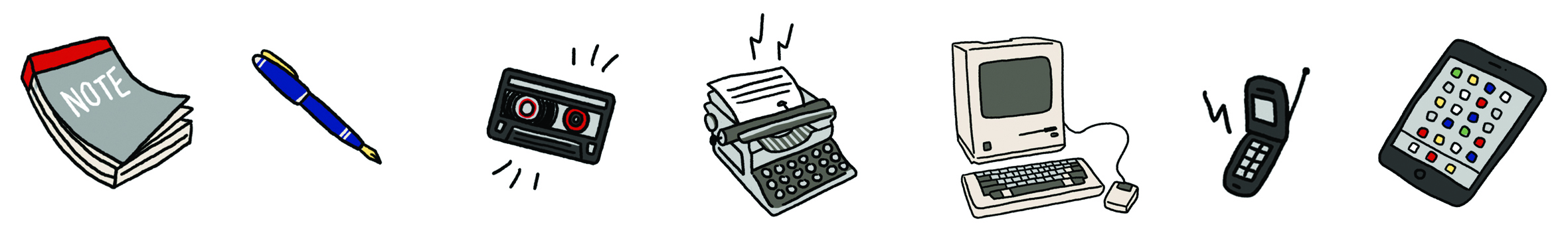

Throughout its 2,600-year history, Buddhism has been closely connected with technology. Buddhism co-evolved with the technological advances of its time. It could even be argued that Buddhism itself was a response to the great shifts taking place in the Buddha’s time, as the first great cities appeared and early clay printing transformed human communication. This period also saw the development of a common written language for the culture of the Indian subcontinent. Sanskrit provided a “platform” for religious communication that had never existed before. The Buddha himself coexisted comfortably with progress and gave several sermons (including his last) in Vaishali, an early city that was also the capital of one of humanity’s first republics.

Buddhism’s growth in Asia was largely driven by the new technology of woodblock printing. Scholars Frances Wood and Mark Barnard note that a Chinese translation of the Diamond Sutra is “thought to be the oldest surviving printed book in the world,” dating back to 868 CE. Buddhism’s organizational structure as a chain of independent monastic communities gave it “portability” across national boundaries, helping it adapt to new cultures and social changes early in its development.

The invention in the 15th century of of movable type revolutionized the Christian world as well. By permitting the widespread dissemination of texts, the printing press liberated the Bible from the priestly elite and made it available to the masses. This undermined ecclesiastical authority and helped give rise to the Protestant Reformation. Those printed Bibles unseated hierarchies. They changed a civilization’s perception of the universe, and of itself. When Martin Luther posted his “95 Theses” letter on a church door in 1517, he was mounting a public challenge to his church’s powerful leadership. His supporters quickly translated it from scholarly Latin into common German and used the printing press, still a relatively new technology, to distribute it widely. According to historian Ricardo Duchesne, more than 300,000 copies were circulated as a result, lending momentum to the Protestant Reformation in an early example of “social media” as a tool for change.

More recently, though it is little known in the West, the Iranian Revolution of the 20th century was technologically driven. The Shah of Iran’s secret police avoided the mosques, where cassette tapes of the exiled Ayatollah Khomeini were copied and shared, taking his message viral. Despite the Western image of Iran’s ayatollahs as stern, bearded, medieval figures in dark cloaks, and despite their fundamentalist beliefs, they were not shy about embracing technology to further their revolutionary goals. To the question “Can technology set you free?” they would probably give a qualified yes—as would the operatives of Al Qaeda and other terror organizations that rely on technology to meet their objectives. They use YouTube videos for recruitment, cell phones and email for communication, and global financing networks to fund their operations. Sociology professor Diego Gambetta of Oxford University and political scientist Steffen Hertog of the London School of Economics and Political Science studied people from 30 countries who had committed acts of political violence. Among those whose academic backgrounds could be determined, they found that 44 percent of them had studied engineering. No other discipline came close.

What are we talking about when we talk about technology? Aren’t we really talking about ourselves? Technology has been a fundamental part of the human experience from the very beginning, since the first hominid built a fire or killed another hominid with a weapon. The first human being to hunt with an ax was a “cyborg” who extended his arm and gave himself a rock-hard “bionic fist.” We are a species that acts on its environment and changes it to serve our ends. And we have learned to do this with the increasingly complex array of tools that we ourselves have created.

We create technology. It is us. It has no moral value beyond that which we give it by its use. To say we’re pro-technology is merely to proclaim our belief that humanity will employ its new technological skills wisely. To say we’re anti-technology is equally beside the point. It’s no more meaningful than it is to say we’re anti-language. We can despise what people say, just as we can despise what people do with technology. But we can’t get rid of either.

In “London,” his dirge for the industrialized misery of 18th-century England, William Blake wrote of the “mind-forg’d manacles” imprisoning the people of his nation. His “charter’d Thames” was a once free-flowing river whose waters had been measured by surveyors and reduced to scientific categorization by the small-minded technologists of his time. Blake’s antipathy to technology was brought on by the impact of the Industrial Revolution, and he held it deeply: “Art is the Tree of Life,” he wrote in his notebook. “Science is the Tree of Death.”

In his poem “America, A Prophecy,” Blake wrote: “Let the slave grinding at the mill … look up into the heavens.” Blake’s mill and its operator were a primitive “cyborg,” fused into one mechanized—and, to Blake, enslaved—being. “You must either make a tool of the creature or a man of him,” wrote Blake’s contemporary John Ruskin. “You cannot make both.”

Needless to say, digital technology has accomplished wonderful things. Most of human knowledge, and large segments of humanity itself, are available to us at the click of a button. Digital technology has aided uprisings in Iran, Burma, and the Arab world. No matter how limited our physical environment, the whole world is available to us in digital form. “I could be bounded in a nutshell,” Shakespeare wrote, “and count myself a king of infinite space—”

But that’s only half the story. Hamlet continues: “—were it not that I have bad dreams.”

Digital technology has its share of bad dreams: The workers who died building Apple products in China (after an aid organization had warned the company of the danger and asked it to change its practices). The time-wasting perils of “Internet addiction.” The online proliferation of hate speech and dehumanizing pornography. Economic inequities, made more extreme by Silicon Valley corporatism. The enslavement of human thought through the design of computer interfaces and the Internet itself. (Jaron Lanier’s book You Are Not a Gadget includes some provocative discussions on this subject.) Not just bad dreams: such things make a “tool of the creature,” and that creature is us.

The real question isn’t can technology set us free? The real question is the perennial one: “Will we set ourselves free?” As they have in the past, Buddhists will undoubtedly look to their tradition’s enduring values for answers. In a community as diverse as Buddhism’s, different answers will arise, some optimistic, some skeptical. There is, and always has been, room for and need for both.

In his first sermon, as described in the Pali canon, the Buddha spoke of a “middle way” between asceticism and indulgence and of that way’s Eightfold Path. That path is still valid and valuable in a digital age. Technology’s value is the value we give it as a society and as individuals, in millions of large and small decisions that are made every day. It reshapes our world into something that can seem unfamiliar and even strange. But we are still in human territory—territory we can navigate with human wisdom and insight, should we choose to do so.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.