In people’s idealized notions of a monk or a nun, one assumption is very accurate: that it simplifies your life so that you can put all your energy into waking up. Of course, not only monks and nuns are committed to waking up. But for many people, regular life is too distracting—which is to say, they are not at a place where they feel they can follow a path, because their ordinary life keeps overwhelming them or dragging them into passion, aggression, and ignorance.

If you have the good fortune to be a monk or a nun in a monastic community, the environment continuously reminds you of when you spin off the path and when you return to it. Somehow you feel cornered—in a positive way—by your own habitual patterns, and there is no place to hide. In addition, there is the ever-present opportunity to practice and study. But it is actually the element of the monastic community that I think is the most powerful element in helping you to wake up.

I lived for ten years as a nun without a monastic community as a member of the Vajradhatu community. It was a lifestyle that was extremely compatible to me. I never looked back. Nevertheless, I don’t know how much real processing was going on, because as a nun in that situation, keeping the precepts was not very challenging—it didn’t dig into my deep hidden places. But when I finally moved to Gampo Abbey the processing became very, very deep and very, very powerful. As I watch people come into that community either as a temporary monk or nun or with a lifelong commitment, I see the same kind of processing occur. It isn’t easy, in the sense that it’s never easy to see your habitual tendencies clearly, but on the other hand it is a very supportive and nurturing environment for continually attempting to see clearly and for being gentle with what you see, and for helping others.

Related: The Precepts: A Special Practice Section

As I travel around, I see how difficult it is in lay life to bring your life to the path because so much is happening. And so in a sense you could say that becoming a monk or nun, and especially living in a community as a monk or nun, makes this much easier. Living as a lay practitioner in the outside world is actually a much more difficult practice. I say this out of respect for the difficulties of ordinary life, the challenges of the nine-to-five job, raising children, the intensity of the work situation, where it is very hard to find any space in our minds. Becoming a monk or nun and living in a monastic community is a much easier practice.

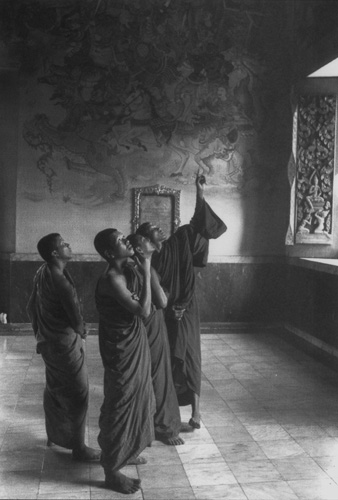

If you become a monk or a nun, you put the desire to wake up in the center of your mandala and everything else stands in relation to that, and becomes a vehicle for waking up further. Your priority is to wake up and you enter a community where waking up is the obvious focus. In Buddhist countries—for example, in Thailand, Burma, or Sri Lanka—great reverence is paid to monks, because in the East there is the concept of merit. Paying respect to a monastic is considered enormously beneficial to oneself. On the other hand, in the West, putting on the robes alone doesn’t do it. You must earn people’s respect through manifesting your sanity. If you are worthy of respect people will respect you, and the fact that you are wearing robes makes them more likely to notice.

People who are constantly lost in confusion in their everyday life are sometimes the people who decide that they want to become a monk or a nun. Now of course the stakes are quite high because the simplicity of the monastic life means that you can’t have sex and you can’t drink or take drugs. Also, an aspect of monastic life that is difficult for people is cutting off their hair and putting on robes, because that seems to separate you out from the rest of the world. Becoming a monastic is a major step, even if it is just temporary.

In the monastic life, you can’t do your usual number of blaming others and justifying yourself. You can’t get away with that. You can get away with it with your husband, or your wife, or your lover, or your children. Within the monastic community, the relationships are equally fraught with confusion and difficulty, but you can’t get away from the realization that your own neurosis plays a big part in the fact that you want to lay the blame on the situation or on somebody else. You’re brought back to yourself in a very profound and inescapable way. This never fits into preconceived idealized notions of becoming a monk or nun. You think that this community is going to be completely sane, that it will have a lot of wonderfully open-hearted people, that it will be harmonious.

The idealized notion is that somehow you’re coming to this place where everything is smooth for you, where everybody does things the way you think they should. And now you have to face the fact that here’s a monk or nun who has been there for a long time and who should, you think, be a model of everything. But for you this person is not a model because they don’t live up to your expectations. This particular monk or nun lets you down, disappoints you, because you have high expectations.

Related: Buddhism’s Second Class Citizens

When you make the actual commitment to stay there for six months, or if you have decided that this is your life’s journey, then all those places within yourself that you do not want to surrender become heightened and you begin to relate in the same habitual way that you have for your whole life. You complain about the food, you complain about other people’s lack of compassion. You complain about a lot of things, but it is like complaining into a house of mirrors.

We’re not talking about trying to create an ideal environment. Enlightened society is not an idealized environment. It’s an environment that actually accepts the imperfections of humanity and encourages you to open your heart and mind and work with other people and situations as they are. Enlightened society is one in which, as you make friends with yourself, your communication with other people gets clearer, more direct, more honest. It minimizes the idiot compassion, idiot patience, and idiot generosity, and maximizes clarity, where you can communicate with people from the heart. You can talk to people about the fact that they lose their temper. Real communication means that you’re not trying to prove yourself right and them wrong.

The motivation for entering the monastic life, either with a temporary or a lifetime commitment, would be that you want to be clear about who you are and want to have enough maitri (loving-kindness) toward yourself so you can benefit others. Wanting to be there for other people with an open heart and an open mind is the only reason that you would become a monk or nun. It isn’t so that you can retreat into a cabin and escape all the messiness of life for the rest of your life. You have to accept the challenge of who you are, and that also means the challenge of living with other people.

When people reach the gateway of novice or full ordination, they really have to think about it; it’s a major step. “Do I want to live with these people for the rest of my life?” So we purposely make it a gradual stepping in. A certain number of people have found what they want to do for the rest of their life. A certain number of people have found that it worked for a while and they thought it was for their whole life, but at one point they changed their minds. Some people know from the very beginning that they would like to try this out just for a little while. Some people want to come and live in the environment and just take the five precepts, with no intention of cutting their hair and putting on robes, but just to experience the environment. Trungpa Rinpoche liked the idea of temporary ordination. This did not exist in Tibet, but it is widespread in Southeast Asia. He felt it was a particularly good idea for young people between high school and college, or between college and career.

Monastic life isn’t tough because you have to work hard all day long. It isn’t tough because you don’t have any time for yourself. It isn’t tough because there is no time to practice, it’s tough because there are no exits and you come up so close to yourself. When I mentioned this to the abbot of Gampo Abbey, Thrangu Rinpoche, he said, “Well, isn’t that the point, that you see yourself?”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.