A few miles north of Green Gulch Farm is Muir Woods National Monument, a pristine stand of old-growth redwoods. Lately, I’m there a lot helping to pickax open the seized soil in Bohemian Grove so that broad-rooted native grasses can reclaim the tight ground. For the last five years, it’s been my civic duty to volunteer in the woods and work on the compacted ground where a giant Buddha was once constructed.

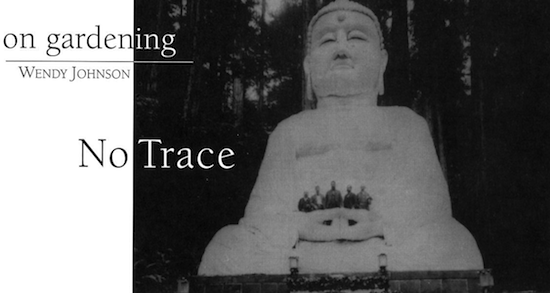

In 1892, sixteen years before the woods became a national monument, artists and writers of the secret Bohemian Club gathered for their yearly all-night encampment in Muir Woods. On this particular occasion they constructed a huge, forty-three-foot-high plaster-of-paris replica of the Kamakura Buddha. No one knows why they chose the great Daibutsu to model, but around this immense figure revelers celebrated the muse of poetry and song. Only the penetrating cold of the woods discouraged the Club from ultimately purchasing Bohemian Grove. They eventually abandoned the spot completely, along with the hulking, one-ton white Buddha.

No trace of it remains. No trace, that is, except for the occasional chunk of plaster poking out of the thick redwood litter blanketing the iron-solid ground where the white Buddha once sat. “Even Buddhas compact the ground,” I mumble to myself, as I bust open the soil of Bohemian Grove.

“When you do something,” Suzuki Roshi repeatedly taught, “burn yourself completely, like a good bonfire, leaving no trace of yourself.” As a Zen gardener, I wrestle with this sentiment. On the one hand, there is just the pure fire of activity happening in its moment, clear and bright. I work hard to open the soil, and I get out of the way. But I also rearrange the landscape with every garden I assemble, leaving ample trace of my activity. My bootprints mark the soft soil of the land. What, then, does it mean to burn myself completely?

These days I turn to plant roots and living soil for my answer. I aerate the soil of Bohemian Grove, but it is the invisible roots of purple needle grass and young tan oak seedlings that are the true reclaimers of seized land. And the vast, fibrous roots of the wild oat plant growing on the fringe of the woods, a plant whose roots would stretch for fifty-four miles if laid out end to end. These roots are the oldest gardeners.

Roots anchor all plants. They take nutrients directly from the soil in exchange for hydrogen. Roots hold and release water. They dissolve obstacles. And roots breathe, Inhaling carbon dioxide as they grow. When roots die they slough off all traces of themselves, providing premier food for the underground sangha of microorganisms that holds up the world.

I realize that it’s a conceit to think that I burn myself completely, leaving no trace. Dedicated effort is needed for maintaining and restoring soil. But the renewal is accomplished primarily by myriad creatures that dwell in the ground. In Bohemian Grove legions of rooted beings and their bacterial brethren swallowed up the forty-three-foot-high Buddha. I’m their garden servant, pecking away at the hard hide of the grove, opening up my own life as I work. I loosen the soil, letting in fresh air so that invisible roots can work with ease, digesting raw earth, leaving no trace.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.