In the wake of the “mindfulness revolution” of the past two decades, it is now common for many people in the United States and around the globe to think of meditation primarily as a tool for cultivating mental health and well-being. Yet even as this perspective has become mainstream, more committed practitioners of Buddhism have articulated the critique that an exclusive interest in health outcomes is misguided, vastly inferior to an “authentic” practice of meditation focused on liberation. A broader perspective, one that looks at the history and the wider context of contemporary Buddhist practice worldwide, may help to examine—and question—some of the assumptions behind both sides of this debate.

Perhaps most surprisingly for some, there can be no doubt that this-worldly health-seeking practices have been closely associated with Buddhism since its very inception. Practical tools for mental and physical healing—including but not limited to meditation—were adapted and elaborated across virtually all of Asia for most of Buddhism’s history, and indeed have often played a major role in the popularization of the religion in its new host cultures. Approaching this topic from a historical and global perspective, however, also brings to light ruptures with the past that have affected and reshaped modern Buddhist notions of health and healing.

Buddhism’s connection with health goes as far back as the Pali canon, the primary collection of early scriptures that was first written down in Sri Lanka beginning in the 1st century B.C.E. and is assumed to represent an earlier oral tradition from India. While medical knowledge is by no means the primary concern of these texts, it is mentioned tangentially in a great number of medical metaphors, similes, and analogies, such as the frequent comparison of the Buddha to a physician and his teachings to medicine. A number of parables and narratives involve doctors, surgery, medicines, and other health matters, such as the famous “parable of the poisoned arrow,” in which the Buddha discourages questioning that would distract a person from dealing with the existential problem at hand. Meditation texts such as the influential Satipatthana Sutta describe the physical components of the body—the organs, fluids, and elements (earth, water, fire, wind, and so on)—in ways that are strikingly similar to lists appearing in Indian Ayurvedic medical treatises from around the same period. Additionally, the Pali Vinaya, or monastic code, lists numerous contemporary medicines and procedures, and specifies whether the Buddha approved or disapproved of each one in turn (spoiler: he usually approves). Finally, several stories in the sutta literature tell of the healing powers of reflecting or contemplating certain aspects of the dharma, such as the seven factors of awakening. These stories seem not to refer to structured meditation practice, but rather to claim that even simply being reminded of the dharma has a healing effect on the body.

We might think of Buddhist healing as one of the first “world medicines.”

Less tangential, and more relevant to health care per se, are narratives in which the Buddha is personally involved in healing activities. In one iconic story in the Vinaya, the Buddha comes across a monk with dysentery who has been abandoned by his fellow monastics. After caring for the monk with Ananda’s help, the Buddha admonishes the sangha. “Whoever would tend to me,” he says, “should tend to the sick.” Other sections of the monastic code discourage monks and nuns from engaging in healing or other “worldly arts” for personal profit, and the Buddha’s words in this story are meant to advocate that monastics care for one another, not for the laity. However, Buddhists the world over have interpreted the story of the monk with dysentery—which appears in many versions in multiple languages—as an imperative to become involved in healing, nursing, and palliative care as an embodiment of the Buddhist values of compassion and merit-making.

With the linking up of the Silk Road and maritime trade routes across Asia, Buddhism began a period of expansion from the 1st century B.C.E. to the 8th century C.E. Aspects of Indian medicine that are reflected in early Pali and Sanskrit texts—stories, metaphors, models of the body, specific therapies—were embedded in Buddhist tradition and came along for the ride. Just as some might refer to Buddhism today as one of the first “world religions” in the sense that it expanded beyond its original cultural and linguistic context, one might similarly think of Buddhist healing as one of the first “world medicines.”

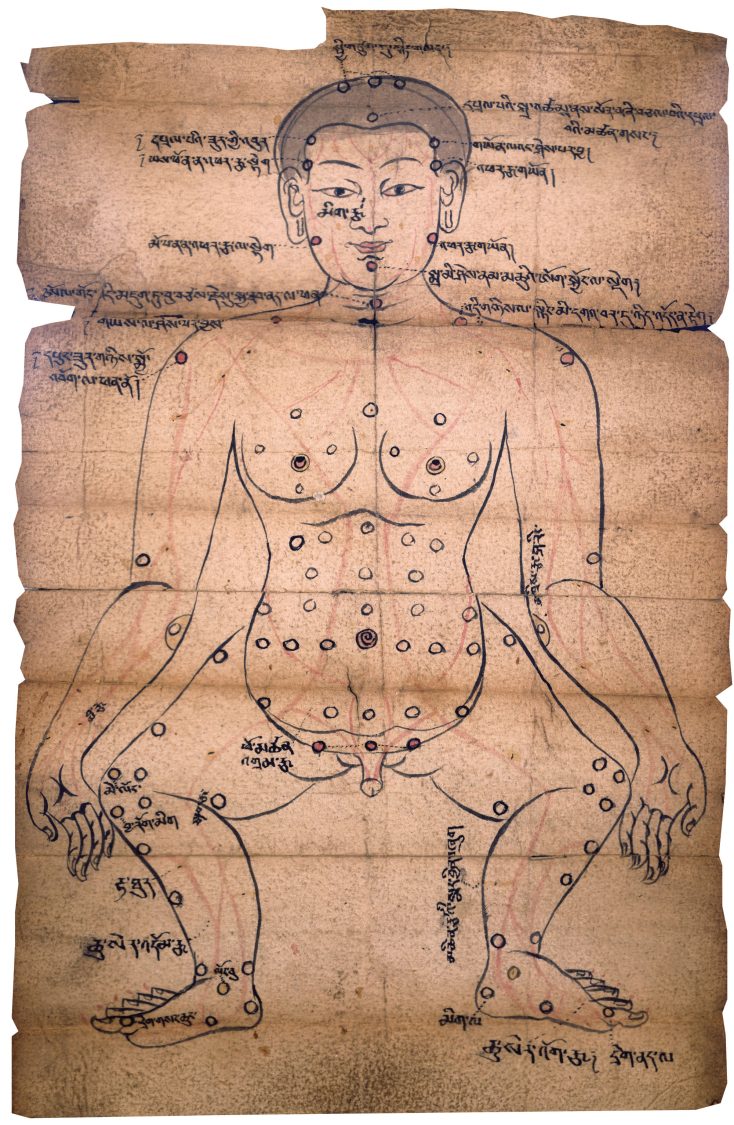

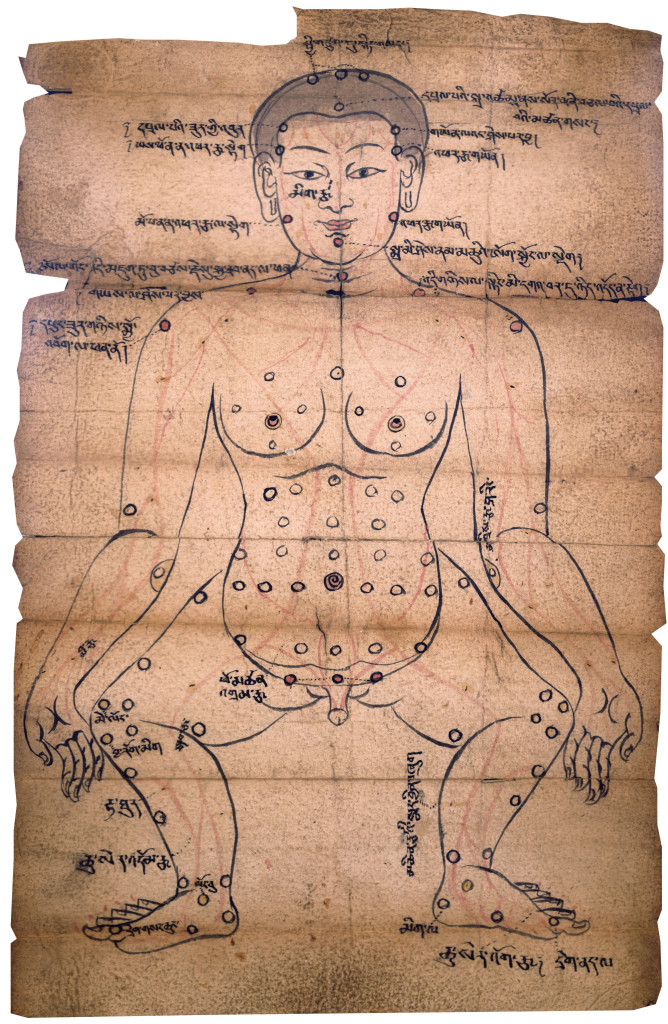

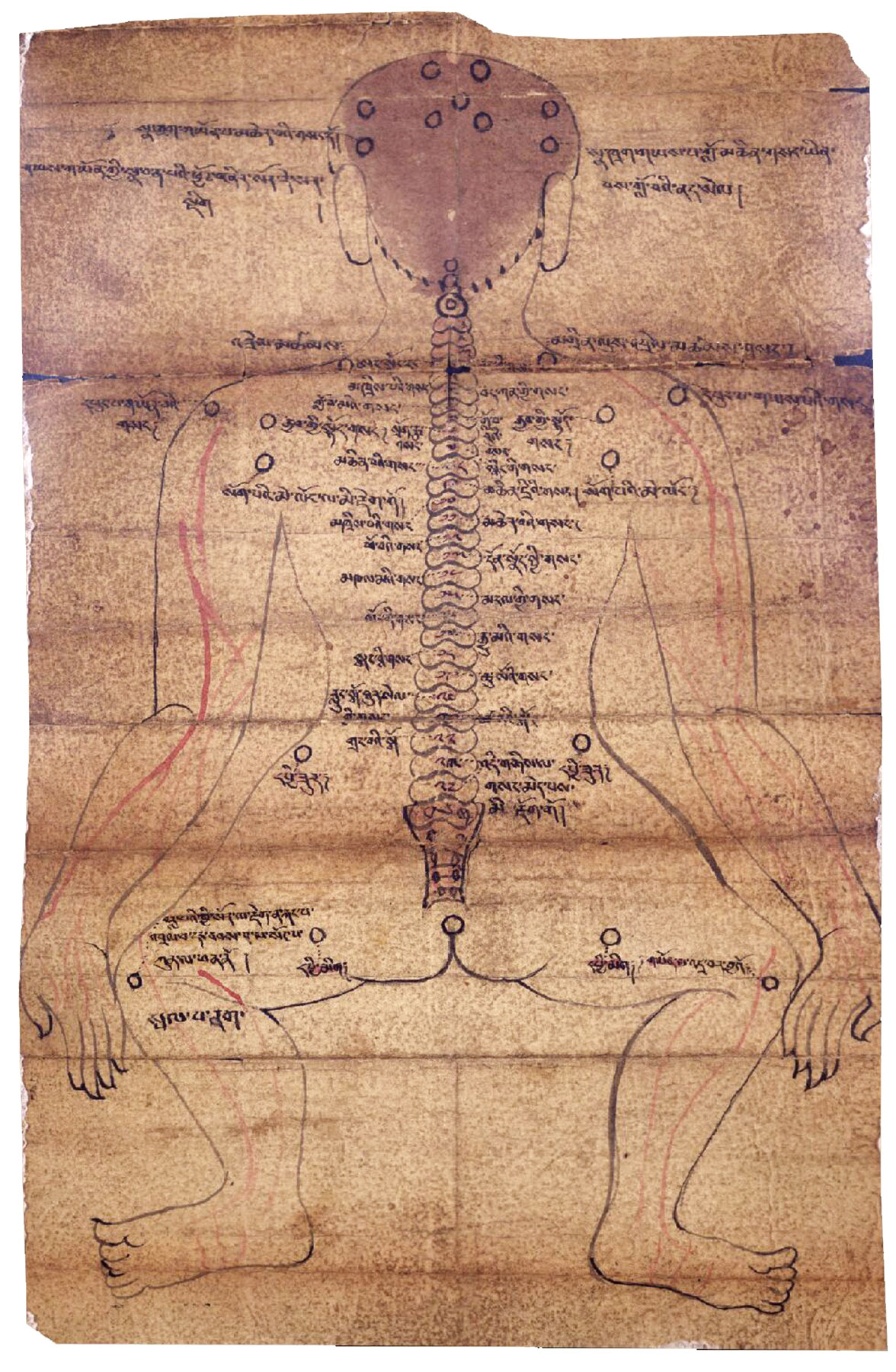

Related: Tibetan Medicine: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Health and Healing

Buddhist approaches to healing were spread by famed South Asian healer-monks who worked as missionaries, translators, and advisers across medieval Asia. Translations and new texts composed throughout the Buddhist world described healing interventions, rituals, dietary practices, and other therapies. These practices were both supported by and contributed to a huge interregional trade in medicinal substances such as herbs, animal products, gemstones, relics, and other magical materials, and were propagated by economically and politically powerful networks of monastic institutions.

As these ideas, practices, and objects traveled along the trade routes, Buddhist healing became a major factor in the religion’s appeal in new lands. In China, for example, Buddhist healing became popular in the early medieval period (3rd to 8th century C.E.) among both the common people and the elite medical officials associated with the imperial court. Indian curative ideas appear in the writings of the prominent physician Sun Simiao and other celebrated medical authors; Buddhist healing rites were organized and patronized by rulers and elites across China; a network of monastic dispensaries, hospices, and asylums were established across the empire; and veneration of Buddhist medical deities such as the Medicine Buddha (Bhaishajyaguru) became an important part of the medieval Chinese ritual calendar.

All of these tools and institutions were introduced to the rest of East Asia via China. The Taisho Tripitaka, the most influential edition of historical canonical Buddhist texts and commentaries from China, Japan, and Korea, contains well over 100 texts from the medieval period that present important medical perspectives: a variety of major and minor sutras, monastic disciplinary texts, ritual manuals, compendia of incantations and spells, meditation manuals, biographies, travelogues, histories, and encyclopedias. This collection of sources includes Chinese translations of healing advice from all over the Indian subcontinent, Central Asia, and parts of Southeast Asia.

Beginning during the period of pan-Asian expansion, but intensifying between the 8th and early 19th centuries, regional differences began to emerge. Buddhist knowledge of all types has always undergone processes of localization in recipient cultures across the world, and approaches to healing were no exception. In most of the Indian subcontinent and along the Silk Road in Central Asia and western China, Buddhism itself (and along with it, its characteristic forms of healing knowledge) was displaced by Islam and Hinduism and ceased to be a major cultural factor. In East Asia, Buddhism became integral to cultural, social, and political life, but the medical terminology and doctrines transmitted from India were gradually replaced in Buddhist writings and practice by native Chinese notions such as qi, yin-yang, and the “five phases.” In specific locations between the first two regions—for example, in Tibet, Mongolia, and most of Southeast Asia—Indian medical doctrines not only thrived within Buddhist circles but also eventually became the basis for forms of traditional medicine that still are widely practiced today.

In time, the divergences in these local and regional developments led to striking differences not only between various regional Buddhisms but also between the sorts of healing methods they advocated. Each culture developed its own constellations of meditations, merit-making traditions, ritual practices, magical substances, incantations, and other therapies specifically targeting mental and physical health, and their own variations on how such techniques related to the Buddhist tradition as a whole. There were many commonalities in medical practice and theory, but also great variations in detail and emphasis.

Despite this long history, a period of modernization began in the mid-19th century that suppressed many Buddhist health-seeking practices. Colonial European powers and Asian elites who identified with the rhetoric and ideals of modernity dismissed many aspects of traditional Asian cultures. To health officials, regulators, and many modernizing Buddhists, the very idea that practicing rituals, chanting sutras, or engaging in mental exercises such as meditation could have real benefits for health seemed to fly in the face of the new scientific medical paradigm. All over Asia, efforts were taken to outlaw, repress, or severely marginalize healers who incorporated religious activities into their repertoires of practice. Japanese legal reforms in 1874 and 1907, for example, specifically outlawed Buddhist healing techniques such as rituals, spells, prayers, charms, and holy water.

In this environment of hostility toward religion and “superstition,” certain modernizing Buddhist leaders, such as the prominent Chinese monk Taixu, chose not to abandon traditional notions but rather to reframe Buddhist knowledge in ways that would make it more compatible with scientific ways of thinking. (These Buddhist engagements with science are discussed in Erik Hammerstrom’s 2015 book The Science of Chinese Buddhism.) For these authors, certain Buddhist doctrines that seemed analogous to scientific theories were cherry-picked as “evidence” of the Buddha’s prescience and the tradition’s compatibility with modernity. The longstanding Buddhist idea that there are tiny invisible creatures floating around in water, for example, was magnified by Chinese authors as evidence that the Buddha knew about germs thousands of years before the dawn of bacteriology. By the mid-20th century, many authors were routinely referring to premodern Buddhist doctrines with contemporary biomedical terminology like “anatomy,” “physiology,” “pharmacology,” “hygiene,” and “psychiatry.” (One of the first to do this in English was Terry Clifford’s Ph.D. thesis published in 1984, Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry: The Diamond Healing.)

As part of this general trend, medical researchers and Buddhist practitioners in both Asia and the West also began reinterpreting Buddhist meditation as a type of psychological therapy. (The history of the selection of mindfulness from among the wider range of Buddhist ideas and practices and its rise to prominence as an object of scientific scrutiny since the 1970s has been traced in an excellent book by Jeff Wilson, Mindful America.) In the crucible of modernization, most Buddhist healing techniques, practices, and beliefs that were widespread and prestigious across the Buddhist world before the mid-19th century now were reduced to “superstitions,” to be discarded as “cultural baggage.” Meanwhile, those techniques that could be reframed as compatible with science—meditation in particular—came to be seen as worthy of scientific study.

The interactions between Buddhism and science over the past 150 years or so have indeed dramatically changed the face of Buddhist healing across the globe. Nevertheless, Buddhist healing practices that one might think of as more “traditional” have persisted and even flourished, despite being alternately repressed and ignored by modernizers. In almost 20 years of field study and research among Thai Buddhist healers, for example, I have seen firsthand that the entire package of Buddhist healing rites—including the invocation of deities, blessings, exorcisms, cleansing rites, chanting, incantations, binding rituals, the use of talismans or amulets, repentance, and confession—are still highly relevant for most Buddhist practitioners in that culture. While discussions of the medical benefits of mindfulness do take place in many Thai Buddhist circles and more educated people follow the research and popular press on the topic enthusiastically, meditation is usually seen as compatible with this range of other therapies, and all of the above are integrated in practice.

I recently attended a celebration at a traditional medicine school in Northern Thailand that included anapanasati (mindfulness of breath) meditation within a ritual sequence that also included chanting to invoke the blessings of various Buddhist figures; spirit possession; the ingestion of blessed substances; and tattooing of protective talismans onto the participant’s skin. These techniques were all undertaken to empower the participants (healers of various types, but mostly massage therapists) in order to protect them from illness and enhance their healing abilities.

It is not just in Thailand that one can see the entire range of Buddhist healing techniques and traditions. Anthropologists working in Myanmar, Taiwan, Japan, in Tibetan communities, and elsewhere around the Buddhist world have reported a similar range of practices and beliefs concerning healing—often, but not always, including meditation. My own ethnographic research currently focuses on the city of Philadelphia, as something of a microcosm of this broader picture. With a team of students, I have been visiting Vietnamese, Chinese, Korean, Thai, Lao, and other temples in the area, as well as meditation centers associated with Theravada, Zen, Tibetan Buddhism, and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). In all of these locations, we have been interviewing group leaders and participants about their beliefs in the health benefits of Buddhist practice.

Virtually everyone we have talked to agrees that there are mental health benefits to the practice of Buddhism, and most say that there are physical benefits as well. But opinions about which practices lead to those benefits differ dramatically. In predominantly English-speaking sanghas, we tend to hear a lot about meditation. Usually it’s mindfulness or vipassana, but depending on the affiliation of the group it may also be visualizations, breathing exercises, moving meditations, or any number of other meditative practices. Meanwhile, the groups that are largely composed of Asian immigrants tend to place value on a wider range of practices, including meditation but also rituals, ceremonies, and other group activities. Among the former practitioners, we often hear about reduction of stress or anxiety; among the latter, we are just as likely to be told about receiving blessings, divine intervention, or good karma. To be clear, our research does not support drawing a stark line between ethnic or linguistic groups, as there are many ways in which these overlap or bleed into one another. Rather than looking to draw divisions between Asian and non-Asian practitioners, or between what have been called “heritage” and “convert” Buddhists, we are primarily interested in exploring and cataloging the varieties of Buddhist healing in a contemporary American city, in all of its complexity and diversity.

Related: Are You Looking to Buddhism When You Should Be Looking to Therapy?

Although linking meditation and science has produced an interesting and often valuable new area of wellness research and practice, our present fixation on one form of meditation is missing the forest for the trees. While research into mindfulness has flourished, many other potential lines of research have been left virtually untouched. In the realm of meditation alone, there are literally dozens of contemplative practices that Buddhists have traditionally identified as beneficial to one’s physical health, including visualizations, mantras, recitation of deity names, breathing and movement exercises, refinement of subtle essences (qi, prana, lung), absorptions into the four elements (earth, water, fire, and wind), and abiding in emptiness. There is also a rich literature on the potential ill effects of such practices, and this too needs to be explored.

Do these meditations have scientifically measurable effects on the body? Can we show that prayers, purification rituals, chanting of sutras, or the use of talismans have concrete health benefits? What is the influence of Buddhist philosophical positions (emptiness, for instance) on the individual health-seeking behaviors of committed Buddhists? How do Buddhist values such as moderation, charity, and fellowship relate to health outcomes in Buddhist communities? Are the health benefits of such practices diminished as they are introduced to new populations in different cultures and languages? Given the breadth and diversity of healing wisdom that has been considered “Buddhist” both historically and globally today, exploring these unanswered questions is critically important.

In my view, Buddhism is proving to be a boundless source of tools, technologies, ideas, and practices for human health and well-being that is only now beginning to be explored scientifically. Moving forward, such research needs to involve collaborations between scientists, scholars from the humanities and social sciences, and diverse communities of Buddhist practitioners. The questions that will arise from such collaborative work should be of interest to all Buddhists from all traditions, and should be an integral part of the conversation we are having about Buddhism’s contributions to modern life.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.