“Draw your chair close to the precipice and I’ll tell you a story.”

—F. Scott Fitzgerald

I recently returned from a pilgrimage into Headwaters Forest in Humboldt County in northern California, where eight of us buried an earth treasure vase in the heart of old growth redwoods. We went into this remote forest 275 miles north of Green Gulch Farm by foot, crossing the line onto barricaded private land and tracking a maze of muddy logging roads for hours to reach the Headwaters grove, high in the saddle of the Elk River drainage system.

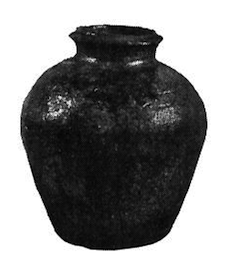

Our journey had actually begun three months earlier, when our sangha was presented with an earth treasure vase. The tradition of the treasure vase has its roots in Tibetan Buddhist practice: an earthen jar is filled with prayers and precious life-enhancing materials and buried in endangered ground, for the healing of the earth.

Our particular treasure vase was made by the monks of Thangboche Monastery in Nepal. A squat, eight-inch-high clay pot dressed in festive Tibetan silks, the vase was alive, a being ready to work. We took it with us everywhere to collect blessings and prayers: it accompanied fifth graders from Oakland as they planted redwood seedlings in the Green Gulch watershed; it traveled to meditation circles of combat veterans and peace activists. Hundreds of warm hands held the treasure jar.

Our particular treasure vase was made by the monks of Thangboche Monastery in Nepal. A squat, eight-inch-high clay pot dressed in festive Tibetan silks, the vase was alive, a being ready to work. We took it with us everywhere to collect blessings and prayers: it accompanied fifth graders from Oakland as they planted redwood seedlings in the Green Gulch watershed; it traveled to meditation circles of combat veterans and peace activists. Hundreds of warm hands held the treasure jar.

Our goal was to plant this vase in endangered earth. We carried it, heavy and packed with prayer, to the front lines of the redwood nation, where forest activists have been protecting the last stand of old growth coast redwoods for the past twelve years. We forged ahead for hours, finally skirting a raw, twenty-acre clear cut to drop down into unmapped primeval forest.

We disappeared, hip-deep in drifts of decayed duff, the moist sloughed-off litter of the ancient forest. Sword ferns towered above our heads. Huckleberry and native Salal grew thick in the snapped-off crowns of dead snags. On the floor of the forest we could hardly move, so dense was the litter of downed logs. We burrowed into the wet, rotten heart of the forest, surrounded by wood-drilling beetles, carpenter ants, and columns of tunneling mites. We followed the trail of the decomposers, boring our way into the decayed core of a vast compost pile. I touched rot from the inside out. Death surrounded us, ate into us, as we pushed through the woods.

The old growth forest runs on rot. It is rooted in decay. A fallen tree five hundred years old takes as long to decay as it has been alive. Host to seventeen-hundred species of plants and animals in its lifetime, a dead redwood tree harbors some four thousand species of life. We too were decomposing and being recombined inside this dark palace of organisms.

After a long time we arrived at the Headwaters grove. Exhausted, we sat down beneath three-hundred-foot-high trees, some with a ten-foot girth. Cold mist blew through the forest, dripping down twisted scarves of Old Man’s Beard lichen that hung like pale shrouds from prehistoric trees. This was in the heart of the forest, and dark. When it was time, we buried the treasure vase in the woods, near the convergence of two icy streams. We dug the soil out with our bare hands. It was the richest and oldest earth I have ever handled. We covered our trace with armloads of litter. It began to rain. Underneath the drifts of rot the vase was already decomposing, radiating prayer out along the fine filaments of duff that uphold a world far beyond form and emptiness.

After a long time we arrived at the Headwaters grove. Exhausted, we sat down beneath three-hundred-foot-high trees, some with a ten-foot girth. Cold mist blew through the forest, dripping down twisted scarves of Old Man’s Beard lichen that hung like pale shrouds from prehistoric trees. This was in the heart of the forest, and dark. When it was time, we buried the treasure vase in the woods, near the convergence of two icy streams. We dug the soil out with our bare hands. It was the richest and oldest earth I have ever handled. We covered our trace with armloads of litter. It began to rain. Underneath the drifts of rot the vase was already decomposing, radiating prayer out along the fine filaments of duff that uphold a world far beyond form and emptiness.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.