Meredith Monk’s latest work, mercy, is the culmination of the performance artist’s legendary career. Robert Coe traces her path from her days as a student in the 1960s to her work today and life as a Buddhist practitioner.

November 1966: U.S. troops are pouring into Southeast Asia, the Summer of Love is still a few seasons away, and a twenty-three-year-old Sarah Lawrence-trained dancer and singer named Meredith Monk performs a half-hour-long solo in the sanctuary of the Judson Church in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. 16 Millimeter Earrings defies easy description except as a stream of tautly constructed sounds and images: of Monk, slowly moving her hands down her face, leaving behind a residue of white lines as “tears”; of Monk, tearing a red wig in anger, sitting on an old steamer trunk. Singing a few bars of “Greensleeves,” she climbs into the trunk and closes the lid while a twelve-foot-high image of a doll burns in a miniature room projected on a screen behind. When the film cuts to an image of flames, Monk rises out of the trunk and stands quietly in profile, the film playing over her body in ecstatic auto-da-fé. A dignified, painterly self-portrait of recurring motifs, both live and prerecorded, Earrings had “the wit of its means and an emotion like that of a Jacobean drama,” observed New Yorker dance critic Arlene Croce. Objective and yet passionate in its rendering of a young woman’s rite of passage into adulthood, Earrings announced the arrival of a major postsurrealist theater artist. It also provided Monk with a key to her artistic self-discovery: the realization that disparate imagery, sounds, and movement could be interwoven in a luminous whole that would speak what could not be spoken in any other way.

Thirty-five years later, the recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant and a three-day retrospective at New York’s Lincoln Center in the summer of 2000, Monk continues to evolve her unique style of music-theater enchantment, undertaking a personal search for what she terms “the wholeness of the human being” through universal myth and lost worlds of cultural memory. Her current production, mercy, a collaboration with visual artist Ann Hamilton, is a series of haiku-like portraits and poems on the theme of human mercy—of “pain, joy, perseverance, continuance.” Its unified score at times evokes Western ecclesiastical chanting, Balkan folk tunes, Inuit throat singing, and screeching crones, but never by imitating these forms, and almost never through the use of conventional language. Instead of words, Monk fashions vocal music from mellifluous syllables and syncopated sighs, hummed vowels and incantatory panting, producing affecting moods of astonishing emotional purity, lodging in the mind as ineffable states of being. Oddity and profundity, unfamiliarity and comfort coexist with a healing energy that has long characterized Monk’s art, and never more so than in mercy—arguably the most fully realized achievement of her remarkable career.

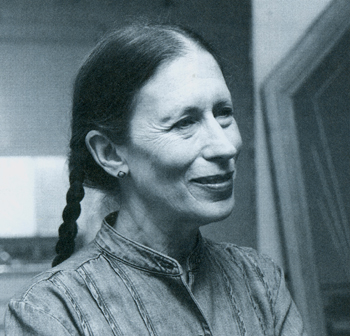

Meredith greets me in her comfortable, sparely furnished loft in lower Manhattan. A few months shy of her sixtieth birthday, she has changed little over the years. Five-foot-two, still trim and beautifully postured, she is dressed today in a high-collared denim jacket, loose-fitting trousers, and slippers, her hair falling in her signature cascade of narrow braids.

Leading me into her kitchen, she calls back over her shoulder, before we’ve even begun our interview, “I feel like I’m just beginning!” Settling down with a tape recorder at the kitchen table for tea (hers) and coffee (mine), I remind her of another time our paths have crossed: the summer of 1978, at Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, where Meredith was teaching a course called “Voice as Image” and I was reporting on Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s Buddhist university for the Village Voice. “Both of us attended a wild rock ’n’ roll record party in the basement of Sacred Heart Catholic Girls’ Junior High School, which Naropa had rented for the summer. The air conditioning had broken down on an extremely hot night, and the sweat was just rolling off us, so eventually a hundred people stripped down to their underwear! I remember Allen Ginsberg capering around in his jockey briefs and you in your pigtails and bra and panties. It was like we were all in the shower together!”

Meredith roars with delight, her face lighting up with an infectious, slightly daffy smile.

“Oh yes! Those were great, great days!”

“You have a huge body of work now,” I tell her. “There is a recognizable imprint on your work that makes it yours.”

Eyes widening, Meredith erupts into laughter. “There is?”

“Of course there is! You’re still Meredith Monk!”

“I am?” More incredulous merriment. “Yes, I suppose that’s true,” she finally admits. “I’ve had a wonderful life. I feel very fortunate to be alive at this time. As they say, ‘blessed human birth.’ I’m just disturbed at times by any categorizations or expectations that keep people from seeing what’s actually there. When I go to a performance I want to be completely surprised. And what was so beautiful about New York when I first arrived was this community of visual and performing artists who were all trying to push past the boundaries of their work and trying new ways of seeing and doing things.”

Studying dance, theater, composition, and voice in high school and at Sarah Lawrence, and performing in lower Manhattan while still an undergraduate, Monk graduated to a garret apartment in Greenwich Village in 1964 and continued to plunge headlong into various gallery, Happenings, and Off-Off Broadway scenes. Interdisciplinary, non-narrative work was beginning to appear in many performance media, but she made her other key discovery alone, at her piano, vocalizing one day in 1965.

“I realized in a flash,” she later wrote, “that within the voice were limitless possibilities of color, texture, landscape, character, gender, and ways of producing sound. From that time on, I began trying to discover the voices within.”

As a dancer Monk lacked an ideal body and struggled at times with conventional techniques, but as a singer she had no such issues: Her lyric soprano eventually stretched three octaves. Backed by her own piano, her lower range can sound as bluesy as any after-hours chanteuse; a moment later she can trip into operatic head tones.

While still in her twenties, Monk began to pursue a new kind of environmental music-theater, employing an evolving musical vocabulary modeled in part after the ostinato patterns of folk music—creating shifting, minimalist tapestries for the voice “to run on, fly over, slide down, cling to, weave through,” she wrote.

“The voice is the original human instrument,” Monk tells me. “It’s the earliest utterance, even before language. It’s the instrument that other musical instruments branch from, and would at times like to have the freedom of. This is how the voice has a transcultural depth: It doesn’t require the screen of language, and in that way it relates very much to Buddhist sitting practice, in that you’re really touching upon nondiscursive energy. Energy for which we don’t have words.”

Monk’s first full-blown music-theater spectacle, Juice: A Musical Cantata in Three Installments, opened in October 1969 at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, with seventy-five white-clad “angels” chanting and humming their way up the spiraling museum ramp, exploring the resonant acoustics of Frank Lloyd Wright’s six-story-tall interior dome. As a quartet of combat-booted refugees in red makeup and clothes trudged belly-to-back up the ramp, the audience followed, moving past thirteen “living tableaux” of performers in front of works by Roy Lichtenstein, until Monk appeared below playing droning chords on an electric organ and wailing like a muezzin. Education of the Girlchild (1972) evoked what the composer described as “the voice of the 80-year-old human, the voice of the 800-year-old human, the voice of the 8-year-old human; Celtic, Mayan, Incan, Hebrew, Atlantean, Arabic, Slavic, Tibetan roots; the voice of the oracle, the voice of memory.”

Vessel (1971), an “opera-epic” about Joan of Arc and Monk’s first widely recognized music-theater masterwork, opened in her loft, where viewers were invited to observe a group of shadowy figures performing tiny, incongruous movements at a distant end of the space. With Monk on electric organ, embodying the voices of St. Joan, performers spoke lines from the George Bernard Shaw play, and a king scattered coins, which a woman ritualistically picked up. Another woman unrolled her long hair, and two soldiers dueled with rakes. The audience then traveled by bus to the nearby Performing Garage in SoHo, where Joan/Monk, painted all in silver now, was tried before a court. The final section of Vessel took place in a nearby parking lot that served as an ancient battlefield, a campsite, and the place of Joan’s immolation. The richest, most thematically unified work that Monk had yet produced, Vessel was an evocation of the close-knit community that SoHo had become, uncovering spiritual, musical, and theatrical means to bridge conscious and unconscious life in a single visionary dream.

Acclaimed as “the Wagner of the Happening” by the French critic Adrian Henry, Monk concluded this period with what most people still consider her greatest achievement: Quarry (1976), an expression of SoHo’s mid-decade theatrical flowering as well as a celebration of its private community. Many people never realized that its secret subject was the Holocaust. “We’re doing what I call the ‘geriatric version’ of Quarryat the Spoleto Festival next year,” Monk tells me, laughingly speculating as to whether she will be able to appear convincing as an eight-year-old child. “Seriously, though—the reason I said yes is that I think the piece has something important to say for today. There’s a built-in sadness in live performance because it can be so fleeting, but that’s the beauty of it, too: It disappears into the air, just goes away, like a sand painting! It’s especially ironic because what interests me is timelessness in work. There are artists who concentrate on being mirrors of the time they live in, and there are artists who concentrate on the cyclical nature of time—on things that recur and other fundamental concerns that exist through any time and place. I think I’m a person like that.”

By 1980 Monk’s career was sufficiently established that she could recreate Vessel in three locations in West Berlin, including the proscenium of the prestigious Schaub hne Theater and the ruins of a bombed World War II-era train station, the latter using 150 German extras and performing motorcyclists. But the countercultural guiding light found herself adapting to changing times through a great deal of personal disappointment and unhappiness.

“I think that in the eighties I was exploring what it was like, number one, to be a person who lived in the city, who was more urban-oriented, and second, to find my own way through this incredible change that was happening all around us. I wasn’t interested in being a big pop heroine or anything—it was more about exploring the darker aspects of what I thought was happening in the culture.”

Four self-described “apocalyptic” pieces followed: Recent Ruins, Specimen Days, Turtle Dreams Cabaret, and The Games, which opened the second annual Next Wave in 1984—a collaboration between Monk and her former life partner Ping Chong (a longtime collaborator). With Chong creating text and design, Monk the music, and both sharing direction, The Games, staged for the L.A. Olympic year, was a cold depiction of a heartless future; it flat-lined in Brooklyn, drawing only 60-percent houses.

“I was at a very difficult time of my life. I realized that I had created most of the difficulties myself. It was like one of those Chinese children’s toys made from straw: You put your fingers into it and pull away; the harder you pull, the more difficult it is to get your fingers out.” Her natural affinity for Buddhism had preceded her three summers of teaching at Naropa, but she still needed to get past her skepticism of organized religion in general, as well as her reluctance to be identified as “Buddhist”; like many artists, Monk was not a joiner. Then a friend suggested that she read Trungpa Rinpoche’s book Shambhala: Sacred Path of the Warrior, “which was a revelation in many ways,” Monk tells me. “The first thing that struck me [after reading it] was that the deep source of my stuckness was terror. I began to have tiny glimpses of the strategies that I used to cover that up—from myself and from others. When the New York Shambhala Center offered an introductory course, I went. During my first interview with the instructor [Martha Rome], I literally cried tears of relief.”

Monk feels very grateful that she’s been able to visit Gampo Abbey in Nova Scotia, where she studied with Pema Chodron twice, in 1997 and 1999. Because of her heavy touring schedule, Monk would need a while to get through all the levels of Shambhala’s training program. “Sometimes I repeated a level a few times, with years in between. But I always felt that the learning process was not linear—although there is a natural order to the levels—but actually prismatic or spiralic. You are looking at the same thing from a slightly different angle; you come to it yet again with new understanding from your practice and your life experience.” In 1998, after much serious consideration, “because it turns your life upside down,” Monk took vows of refuge with Khandro Rinpoche in New York City.

I ask the burning question, at least for me: “So, Meredith—how do you see Buddhism touching your work?”

“It’s touched my work, and it’s touched my life! I’ve always said that I was ahead of my years as a young artist, but as a person I was barely aware! I think the artist on stage and the vision of the work always had an integrated quality, but I was impatient as a younger person. It was all so easy for me as a performer. I didn’t really see that other people were sometimes very challenged. And I think that I’ve learned about working with people, and being with people. And then I turned fifty—feeling great, thinking, ‘Boy, this is an easy transition.’ And then suddenly I was getting onstage and experiencing this incredible existential fright. It was like, ‘Here I am, and there are two thousand people out there!’ And I would just start shaking. Some of it had to do with my instrument: I couldn’t get my high E’s anymore. I had to adjust to what was going on in my body—including my change of life, and all the hormonal things that people go through with that. I didn’t know how to relax with the cycle of aging. I wondered, would anyone really want to watch a woman who’s over fifty, you know? There were some performances where people could see that I was frozen in fear.

“And then I read something that Pema Chodron wrote about Milarepa in the cave. These demons come in, and he invites some of them to tea—and they leave. There are only a few really hard ones left, so Milarepa opens his mouth and says, ‘Come in,’ and they, too, disappear. So [in November 1993] I was doing a performance in San Francisco, and I remember getting onstage and feeling fairly relaxed, and then this incredible fear started up again. But this time, instead of pretending that it wasn’t there, I let it come. It was like, ‘Come in.’ I wasn’t thinking this, of course, because you’re not really thinking when you’re performing, but it was happening—it just came, like the ocean, and then it went, and then it would come back, and then it would go. My partner Mieke was in the audience, and she said it was incredible, and very moving to see. The audience was totally part of a process that allowed them to experience our vulnerability as human beings. So that was the beginning of working my way through. I don’t feel that way these days. I’ve found a deep relaxation as a performer. I don’t even expect anything vocally anymore. My voice is feeling great, relaxed, very flexible—and I feel that what is going on, is going on!” I tell her that it sounds as if her performing is becoming more and more a part of her practice.

Meredith looks at me earnestly. “Hopefully what you’re doing as an artist is bodhisattva practice. It’s the same thing; there’s no separation at all.”

Beginning in 1999, Monk’s desire to merge her life and practice more completely—to work with a beginner’s mind—launched her on what became her current mission of mercy. For the first time, Monk took on an outside collaborator: Ann Hamilton, a widely acclaimed visual artist and fellow recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant.

“I usually create my own images, my own visual aspect, but I just thought it would be really interesting to work with a visual artist for the first time in that way. And I think of all the visual artists in that field I felt the closest to Ann. She’s not a practicing Buddhist, but her work in essence shares Buddhism’s values—we both have a kind of silence about our work, and a lot of space, and an interest in mystery and what can notbe seen and what cannot be articulated. For me, it was like throwing myself off the edge of a cliff. It was terrifying because I’m usually in charge of my entire world, and Ann is, too. So it became a process of trusting someone and letting go of ego territories and keeping the integrity of both of our sensibilities.”

The idea of “mercy” as a subject came from Monk. “We didn’t want to do a literal piece about mercy, but gradually it became a piece about help and harm. Ann became interested in what came from the mouth and what came from the hand, in relation to help and harm. You can scream, you can ask for help, you can soothe, you can kill someone—you can also heal someone. For me, stemming from my practice, I’m always contemplating human nature, hopefully not in a judgmental way, but to consider extremes of human behavior. And I became very interested in an act of mercy as something that one does naturally.”

Outside, dusk is settling. Meredith introduces me to her twenty-four-year-old turtle, Neutron, who has been hiding under a chair. Later, it occurs to me that just as Tibetan Buddhism has exemplified our culture’s fascination with the exotic, while in reality embodying a much more grounded vision of “ordinary mind,” so has Meredith Monk. “Pema says that you really have two choices, particularly as you go along in years,” she tells me at one point. “One choice is that you get more and more armored and hold on to a fixed image of yourself and how you think other people see you: You know, ‘This is Meredith Monk.’ The other choice you have is to become vulnerable and actually soften. And I think that’s what happened to me when I started the Shambhala training. So that when this thing happened in my life cycle, and the rug really got pulled out from under me, I chose to allow myself to become very vulnerable.”

I read her a passage from Trungpa Rinpoche’s writing: “’We have to rediscover something in our lives. Is it possible? It is possible, extremely possible.’ When I read this not long ago, I thought of your work—because although you don’t like to tell viewers or listeners what they should think, at the same time there are discoveries to be made.”

“I don’t like to set up a manipulative situation at all, it’s true. I really prefer to leave a space for each human being. I like having an openhearted situation, and I’m also more and more interested in the radiance of the performers—the generous spirit of the performers. I’m also very pleased that Ann and I have become such close friends. Working with her has given me a wider perspective—the idea that ‘me’ maybe isn’t that important. mercy starts with an image of the two of us sitting across from one another at a table, which is how we started work on this piece. I think being willing to really listen and be open to another person is the subtext of the piece.

“Because if you’re really willing to listen to someone,” Monk tells me, “it’s already an act of mercy.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.