On March 11 and 12, 2017, 19 Tibetan and Himalayan women, the 17th Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje, and 5 fully ordained nuns from Nan Lin Nunnery in Taiwan took bold steps to revitalize full female ordination in Tibetan Buddhism. The ceremony was held at the sacred Buddhist site of Mahabodhi Temple, in Bodhgaya, India. In fact, it took place directly under the generous boughs and fluttering green leaves of the Bodhi tree (or probably more accurately, the Bodhi tree’s distant progeny). This famous tree stands next to the Vajra Seat, the original spot where the Buddha is said to have become enlightened, in around 450 BCE. The extraordinary nature of the site, and the spectacular temple that was built there, made a most appropriate stage for the dawning of a new day in the history of the Tibetan Buddhist sangha, especially its women. A fortunate witness to this happy event, I offer here my attempt at anumodana: a traditional Buddhist expression of rejoicing in the meritorious actions of others.

Reviving lost lineages of Buddhist female ordination has been a goal of many, in both Asia and around the world, for the past century at least, if not much longer. Most lineages of bhikshunis, or fully ordained female nuns, have either died out or never existed in the first place in many parts of the Buddhist world, including Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, and Tibet. In Korea and China, full female ordination never completely disappeared and has been reinvigorated since the early part of the 20th century. More recently, women from countries following other Buddhist monastic traditions have taken ordination from one of the strongest living bhikshuni lineages, namely the Chinese Dharmaguptaka, in Taiwan. These women have then attempted to transfer their ordination back to their local monastic contexts. In a few cases, such as in Sri Lanka, they have met with some success, in spite of reticence on the part of conservative monks and laity. But such efforts have largely languished in Thailand despite several attempts, and the situation is similar in Tibetan communities.

Related: Bhikkhuni Ordination: Buddhism’s Glass Ceiling

In 2007, a conference of international Buddhist monastics and academics was convened at the University of Hamburg, Germany, under the auspices of H.H. the 14th Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso, to try to rectify this situation. As excellent as the papers and discussions were, initiatives coming out of that conference stalled as well. I was present at the meeting, and heard the Dalai Lama speak fervently about the specific talents of women and their ability to provide leadership in Buddhism. But he added that he is not a dictator and cannot simply command the major Tibetan monastic institutions to accept a newly constituted Tibetan bhikshuni sangha. Instead, he said, he needs a broad consensus on the process of reviving the female monastic lineage. And that has proved elusive, despite prodigious efforts on the part of Tibetan scholars, at the behest of the Dalai Lama and other leaders, to scour the Vinaya—the ancient Indian monastic code—and Tibetan historical writing

for the appropriate procedures and precedents.

But the Karmapa—Ogyen Trinley Dorje is one of the two claimants to that title—and other leaders of Tibetan Buddhism have been eager to move forward. While visiting Harvard Divinity School in spring 2015, the Karmapa declared in a lecture to Harvard Buddhist Studies faculty and students that there had been enough research and discussion. It was time for action. Without setting firmly in place the traditional “four pillars,” or fourfold assembly—the female and male monastic sangha and female and male lay community—Buddhism could never really flourish. Thus he announced his intention to begin the ritual process that would lead to a fully ordained Tibetan female monastic sangha.

There are three sets of monastic vows for women: the preliminary shramanerika, or novice vows, then shikshamana, or training ordination, and finally the full bhikshuni ordination. The first ceremony would confer the shramanerika vows, but would eventually lead to the recipients’ full bhikshuni ordination a few years thereafter. The Karmapa sought an outcome that is as ritually correct as possible. And so in light of longstanding monastic and pedagogical practice, he wanted the eventual bhikshunis to receive all three ceremonies from the same bhikshuni mentors, beginning with the shramanerika vows, even though many Tibetan nuns have already taken those vows. This ceremony requires five bhiksunis to perform, so the Karmapa’s plan entailed locating and inviting five nuns from another Vinaya lineage, since the Tibetan Mulasarvastivada tradition has no living bhikshunis. These turned out to be the five women from Nan Lin Vinaya Nunnery in Taiwan, celebrated for its fine monastic discipline in the Dharmaguptaka tradition. Although such lineage-crossing has already occurred many times in Taiwan, it is the first time it has been attempted in a Tibetan-sponsored context.

When I heard the Karmapa announce his decision in his talk at the Divinity School, I decided right then that when the first ordination ceremony took place, I would be there to witness it—even though as a layperson I wasn’t entirely sure if I’d be allowed to. I had an immediate sense of the indubitable goodness of the event, a goodness that called for witness. Having taught and written about women in Buddhism for most of my working life, I readily recognized the significance of the decision. It meant extraordinary support, at the highest levels of Tibetan religious hierarchy, for women’s education, access to leadership roles, and general cultural status, all of which are lacking in Tibet, just as they are in most of the rest of the world. It was a chance for the Tibetan community in exile to make a mark on the world stage, and an opportunity for the kind of earnest and creative human interaction that would boost the confidence of women in Buddhist societies.

I discovered in February 2017 that the ceremony was scheduled to happen during the Arya Kshema retreat for nuns and other women in the following month. It was very inconvenient timing for me, but in a moment of blind conviction I bought a ticket and put myself on a plane to India. It felt a bit like what Zen teachers sometimes call “not-knowing”—when body and mind act as one, with the body sometimes knowing more than the mind.

The 36-hour trip was not quite as bad as I feared, probably because I had already steeled myself. Still, deeply exhausted when I finally arrived in Bodhgaya, I glanced at the note that Michelle Martin, an old friend and one of the scholars on the Karmapa’s translation and reporting team, had left for me early that morning at my hotel. She would be at the Arya Kshema prayers all day, and I should come find her.

Really? But after a brief nap, there I was, rising and setting out to the Karmapa’s temple, somehow remembering my Indian tuk-tuk (autorickshaw) skills from years past. I found the huge modern shrine room filled with over 500 people, mostly Tibetan or Himalayan nuns, Tibetan guards, and Chinese lay patrons, along with the requisite array of Westerners, and a few Tibetan laypeople (Bodhgaya does not have many resident lay Tibetans). And there was H.H. Karmapa on the throne. I found a seat beside Michelle and a doctoral student from Northwestern University, Darcie Price-Wallace, who is doing research on the Tibetan bhikshuni issue, and settled into hours of chanting with them all. They were doing the long-life ritual of the Tibetan female deity Tseringma. What better thing in the world could there be to do but sit and chant sadhanas [meditative prayers] with a large assembly of Tibetan nuns?

Related: Photos: Tibetan Buddhist Nuns in the Himalayas

In the breaks, I learned from Michelle and Darcie a little of what had been going on. They had been observing a series of remarkable evening sessions between the visiting nuns from Taiwan and the ordinands, along with one Chinese nun translator. The Taiwanese bhikshunis were instructing the Tibetan aspirants in all manner of bhikshuni etiquette and comportment. Later during my stay, I managed to attend one of these sessions, and I was enthralled by the graciousness, joy, and simultaneous seriousness with which the lessons proceeded. But on that evening we could not find where the nuns were meeting. We tried again during the first morning break the next day, but once again, we could not find them.

The ordination ceremony was due to start on that very Sunday, and this was now already Saturday. Still, no one seemed to know exactly where it would take place, except that it would be somewhere in the Mahabodhi Temple compound. Nor did anyone seem to know what time it would begin. All that aside, this was the first time I had ever been in Bodhgaya in my life. Anxious to see it, and also thinking that perhaps we might find the nuns and the Karmapa’s people there setting up for the next day’s events, I set out across town for the compound with my buddies after the morning services.

Set below ground level, doubtless because of its age and the fact that it has been excavated, the compound looked to me like something parachuted in from another time and planet. The temple, erected originally by King Ashoka in the 3rd century BC and renovated in the 5th to the 6th century CE, is redolent of a time in India when Buddhism was at the height of its powers. The Karmapa really knows what he was doing in having his innovative ritual carried out here, I thought, in the midst of such tradition-laden antiquity and potency.

An array of pilgrims from all over the Buddhist world—Sri Lankans, Nepalis, Japanese, Burmese, Indians, Tibetans, Koreans, Chinese, and others—were walking round and round the three concentric circumambulation paths that are set around the temple, chanting prayers and bearing flowers.

We wound our way down to the innermost path, and halfway around the circuit we spotted a few Tibetan nuns mulling around where some fancy carpets and two desks were set out on a slightly elevated platform of old stone and marble against the west side of the temple. As we stood there, more nuns began to stream onto the platform. A halting conversation with one of them confirmed it: they had already started the vow ceremonies today!

Thus did our not-knowing turn into great luck. As we later learned, the nuns had decided to hold the ordinations the day before the celebratory ceremony (the event that had been announced). They were concerned that ordinations for 19 people would take a long time, and they needed to be done before the Karmapa could celebrate them. And so no one was there to observe from the Arya Kshema crowd at the Karmapa’s temple or anywhere else—except the pilgrims (who seemed to be paying little attention to what the nuns were doing)—and us.

The postulant nuns began to line up, and the master abbess (a dignified woman probably in her late forties), the teacher (who was somewhat younger), and three assistants from Nan Lin took their places behind the desks. What followed was a gracious, methodical process that ran through the greater part of the afternoon. One by one, the nuns approached the desks, kneeled, and repeated a series of vows and answers to questions ritually posed by the master abbess and teacher. The words that the ordinands had to repeat had been printed up in Chinese, along with Tibetan transliteration, and although none of us managed to get a copy of those words, I assumed they were straight out of the Dharmaguptaka procedural texts.

At one point it occurred to me that here were ethnic Tibetans kneeling in front of ethnic Han, in what might have been viewed as an ironic reflection of the Chinese domination of Tibet; but such considerations of politics and identity were entirely irrelevant in this context. The atmosphere was one of kindness, mastery, order, and trust. The ritual proceeded smoothly and beautifully. Some young; some middle-aged; one in her thirties, to whom we had spoken the day before; and even one older one, maybe in her seventies, who seemed entirely strong and determined—each nun took her turn to bow, receive her vows, and then return to her seat on the carpet. At some point toward the end, someone sprinkled flower petals, which scattered over everyone and everything in the late afternoon breeze.

The next morning we returned to the Mahabodhi Temple, now for the scheduled event. Hundreds of monastics, patrons, and laypeople sat in front of the Karmapa, who was ensconced on a high throne. They were in a large open area just outside the inner circumambulation route where the ordinations had taken place the day before, part of which was still under the broad boughs of the Bodhi tree.

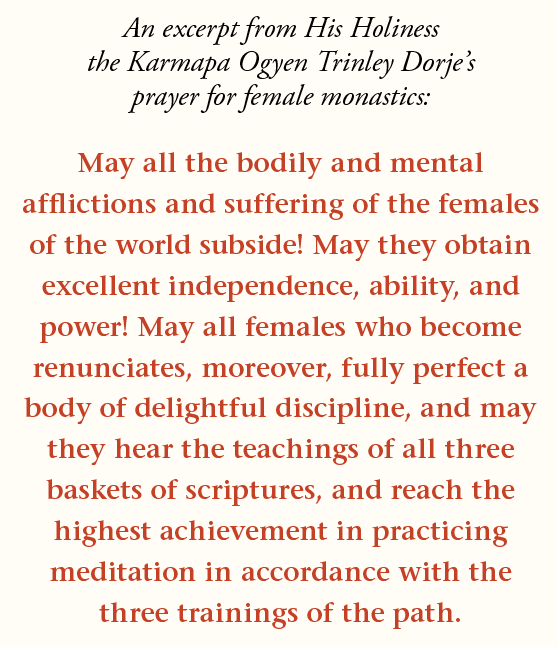

His Holiness’s entourage distributed copies of a new prayer in Tibetan, composed a few years ago by the Karmapa himself. The title alone says a lot: A Practice to Spread the Buddha’s Teachings for Women in General, and in Particular for Female Clerics, Based upon Merging Precious Noble Avalokiteshvara with Noble Ananda: Clearing Out the Suffering of Multitudes. The prayer speaks at length of the importance of women in Buddhism and invokes rarely seen female forms of such Buddhist enlightened figures as the bodhisattva and arhat. It identifies the Buddha’s close disciple Ananda, who argued with the Buddha on behalf of admitting women to the ordained sangha, with the Mahayana bodhisattva of compassion Avalokiteshvara. It provides prayers and rituals for women to practice in order to remember, and be empowered by, the special concern that Ananda displayed for women’s flourishing. And when I looked up, I noticed that hoisted behind the Karmapa’s throne was a large painting of Avalokiteshvara with rainbow rays emanating from his right hand, on top of which rode a small image of the Venerable Ananda inside a rainbow circle. It is likely that this is a new icon, designed to match the visualizations provided in the prayer.

In the next days, back in his temple, the Karmapa spoke further about the importance of women in Buddhist monasticism. He wanted to make his intentions clear and said he feared that in all the commotion of the ceremony he might not have managed to say what he wanted. He reiterated that the move was not in response to Western feminism, but rather came out of his own wish that women should enjoy the benefit of full ordination. For him this had arisen when, some years ago, he first began the tradition of the yearly Kagyu New Year’s Prayer ceremony at Bodhgaya. At that time there was consternation about where nuns should sit in the hierarchical monastic assembly, and what to do about the fact that most had low status because they did not have full ordination. The Karmapa wanted to change this, and so began the research and planning that culminated in this year’s event. Careful scholar that he is, he also mentioned a few precedents in Mahayana Buddhism for connecting Ananda with the compassion of Avalokiteshvara. His determination was palpable and his bold vision evident in the clear gaze of his eyes.

How infectious and compelling this vision is became clear to Michelle, Darcie, and me when we spoke later with Tsultrim, one of the 19 nuns who had taken the precepts. We asked her why she had decided to take on the challenge of keeping 364 bhikshuni vows (this is the number for the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya; apparently the bhikshuni vows she will eventually receive will be from the Tibetan tradition). This will be especially challenging since she will be living not with other bhikshunis but rather in a shramanerika nunnery, where everyone else will only be observing ten vows. She answered that she was inspired by His Holiness and simply wanted to help realize his intentions. She said that she and the others feel encouraged, and that they have the moral support of the Karmapa. She is fully aware that the world will be watching how well she and her sisters will manage as the years unfold. But she and the others simply want to do it. Once again, I thought, an instance of not-knowing—this time

most pure and momentous.

Our conversation with Tsultrim was graced with many smiles and soft laughter, and the three of us basked in her kind demeanor. I was struck by the happiness that seems to come with monastic discipline. This was more evident yet in the nuns from Nan Lin, who displayed an astounding presence and dignity as well as confidence in their discipline. They wore their accomplishments graciously—and with a twinkle in their eyes. In the new mentee coaching session I observed, they explained various monastic restrictions with a surprising sense of humor, casualness, and intimacy. “Wouldn’t it be embarrassing,” they asked, with much giggling all around, “to have all sorts of extra robes packed away in one’s room for one’s personal use?” Well, then, they told the new nuns, the monastic rule is that all gifts of robes that nuns receive should be given to the community as a whole. Later, nuns can request new robes from the community when they need them. The bearing of the Nan Lin nuns reminded me in turn of the awesome Bhikshuni Myongsong Sunim of the Korean Buddhist Jogye Order, whom I had seen for the first time at the conference in Hamburg in 2007. I had never before seen a woman with such deep confidence and such a complete absence of the scars of obeisance to patriarchy. At the forefront of the revived bhikshuni lineage in Korea today, Bhiksuni Myongsong Sunim had the temerity to publicly reprimand the male leaders of the Buddhist world at that Hamburg meeting. She urged them to catch up with the Korean sanghas and to stand on the right side of history. Her points seem to have made a strong impression. It is with these vanguards of a new age of female Buddhist leadership that I rejoice in solidarity and support, just as I admire and rejoice in the bold leadership of the present Karmapa, who is working to make things right. I myself am a mere witness, standing at the edges of these fateful developments under the Bodhi tree. Yet I cannot help but feel encouraged as a woman, as well as a citizen of a troubled world much in need of moral leadership of every kind.

Steps to full ordination for female monastics in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition

On her path to full ordination as a bhikshuni, an aspiring monastic must pass through three stages of training in meditation, philosophy, and the Buddha’s teachings:

Shramanerika (getsulma) or novice ordination consists of 10 precepts; in Tibetan Buddhism these are subdivided into 36 precepts.

Shikshamana ordination, marking a probationary or training stage, consists of 12 precepts in the Tibetan tradition. Bhikshuni ordination consists of 311, 348, or 364 precepts, depending on the Vinaya tradition. For more information, visit: http://thubtenchodron.org/2013/03/different-nuns-vows/.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.