It can sometimes seem that Buddhist practice and scholarship inhabit different universes. But on closer examination, the boundaries between the two are much more porous than might originally appear. Through translating and transmitting sacred texts, scholars of religious studies shape how practitioners envision their connection to the sacred, thus reshaping the framework in which practice takes place. At the same time, the questions that emerge from religious practice often form the foundation of scholarly inquiry. Still, in the contemporary American religious landscape, the gap between the two can seem insurmountable.

For the past four decades, Robert Buswell has been working to bridge this gap. A former monk, Buswell has lived his life at the intersection of Buddhist study and practice, and has dedicated his career to demonstrating the synergistic relationship between the two. The author of seventeen books, the founding director of UCLA’s Center for Korean Studies and Center for Buddhist Studies, the recipient of the Chogye Order’s prestigious Manhae Grand Prize, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the first scholar of Buddhism to be elected president of the Association for Asian Studies, Buswell is a formidable scholar, and he has used his role within the academy to draw attention to Buddhism as it is actually lived.

Drawing from the Korean Son (Zen) tradition, he has highlighted how doctrinal understanding and meditative practice have enriched and enlivened each other throughout Buddhist history and in contemporary monastic practice today. By hosting international conferences with Buddhist universities and monastic orders, he has fostered dialogue between scholars and practitioners, both in the United States and in Korea. In addition, he has edited and translated comprehensive collections of Korean Buddhist materials, bringing many of these texts into English for the first time. And through his own dual role as a scholar-practitioner, he has demonstrated how scholarship and practice can support each other in daily life. In all this work, Buswell has laid the foundation for how contemporary scholarship and practice can come together in the decades to come.

Buswell’s path to Buddhism began when he was in junior high school. “I actually wanted to be a cosmologist because I was interested in the big questions of how the universe came to be,” he told Tricycle. “One question that stuck in my mind was: How could I live without exploiting other people?” In an attempt to resolve this question, he turned to Western philosophy, reading the works of Kant, Hegel, and Schopenhauer. Although he encountered many possible answers, none of these texts provided practical methods for how to actually live without causing harm.

A couple of years later, as a sophomore in high school, he was assigned Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha in an English course, which he considered a “revelation.” “I immediately considered myself to be a Buddhist, even if I had little idea at that point as to what it might mean,” he later reflected in The Zen Monastic Experience. Obsessed, he began to read everything he could find related to Buddhism, from the Lotus Sutra to The Tibetan Book of the Dead. When he stumbled upon Nyanaponika Thera’s The Heart of Buddhist Meditation, he felt that he had found his answer at last: a practical technique that would help him live without exploiting others. “I finally knew what I would be doing with my life,” he says.

Determined to deepen his understanding of Buddhist teachings and practices, he began college at the University of California, Santa Barbara, the only UC school at the time with a religious studies department; in his first year, he started learning Sanskrit and Chinese so that he could read and translate Buddhist texts. After a year, he had taken every course on Buddhism that the school offered, and he decided it was time to “just go off and do it”—to travel to Asia and become a monk. A professor put him in touch with a Theravada monk in Thailand, who arranged for Buswell to enter Wat Bovoranives in Bangkok.

In Thailand, Buswell was confronted with the discrepancies between the idealized accounts of Buddhism he encountered in books and the practical reality of monastic life. On a trip to northeast Thailand, he met with the renowned Theravada monk Maha Boowa and asked for a meditation method that would help him achieve enlightenment; instead, he was told that “the only method is no method” and he needed to figure out what worked for him based on his own experience and interests. “His response was telling and my first real lesson in how to live Buddhism rather than study Buddhism,” Buswell reflected in a recent commencement address. “It was a lesson I took to heart.”

But after a year, he decided that staying in Thailand wasn’t viable—between the climate and living off alms rounds, he frequently found himself sick. He had met some Chinese monks during his time in Bangkok, so he decided to give Chinese Buddhism a try.

He ended up in a hermitage on Lantau Island in Hong Kong, where he lived and studied for a year, reading Chan texts for four hours a day. Though he learned a lot about the Chinese textual tradition, he came to miss the experience of practicing in community. Back in Thailand, he had met Korean monks on pilgrimage and learned of the strong communal practice tradition there, so he decided to set off for Korea.

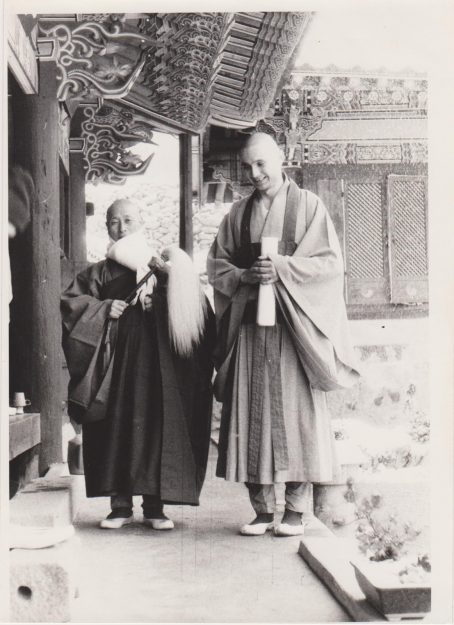

There, he took up residence at Songgwang-sa, one of the oldest temples in Korea. Considered one of the “Three Jewels Temples” in South Korea, it is one of the twenty-five head monasteries of the Chogye Order. Though originally founded in 867, it fell into disrepair until the 12th century, when the Son master Chinul transformed it into the institution it is today—and laid the groundwork for the distinctive style of Korean Zen, or Son, practice that Buswell encountered there.

When he first arrived, he didn’t speak a word of Korean, so he would communicate with the monks in writing using literary Chinese. After finishing his first retreat, however, he realized that he needed to learn Korean in order to understand the meditation technique more deeply. “That’s what started my scholarly career: trying to understand this type of meditation, which was so different from the way Theravada Buddhism approaches meditation,” he says.

In an effort to understand the unique features of Son meditative practice, each spring and fall he would immerse himself in study; each winter and summer he would participate in meditation retreats. Buswell cites this constant back-and-forth between scholarship and practice as a distinctive feature of Korean Buddhism, and it shaped the trajectory of his career. “My scholarship has benefited from my practice, and my practice has always been framed by my study,” he says. “This was rooted in the rigorous combination of doctrinal study and meditation that I experienced at Songgwang-sa.”

But over time, Buswell found that he “could not shake the pull of scholarship.” After two years at Songgwang-sa, he and a couple of his fellow monks decided to translate some of the dharma talks of Kusan, the head teacher; this project turned into the short book Nine Mountains. Two years later, Kusan asked him to translate the works of Chinul, the reformer of Songgwang-sa; Buswell agreed if he could finish the project in one “off” season, but he ended up devoting three off seasons to the task and produced what would eventually be published in 1983 as The Korean Approach to Zen: The Collected Works of Chinul.

After seven years of monastic life, he returned to California in 1979, ostensibly to explore publication options for the book. While he was staying at a Zen center in Berkeley, Lewis Lancaster, a professor in the Department of East Asian Languages at UC Berkeley, invited him to sit in on his seminars, and soon, he enrolled at UC Berkeley to resume his BA. “I realized that I was a much better scholar than I was a meditator,” he quips, “so why not accept it and continue my studies?”

He remained in monastic robes for his first two quarters; once he decided that he wanted to stay in the US to complete undergraduate and graduate studies in Buddhism, he disrobed and transitioned into the role of scholar and lay Buddhist practitioner.

As a graduate student, he was startled by the impression of Buddhism he encountered in Zen literature and scholarship. “If you read the normative literature of Zen, it’s filled with iconoclastic stories of Zen masters burning Buddhist icons and books,” he says. “But when you’re in a meditation hall, there’s none of this at all. It’s a very rigid, disciplined way of life, which is based on sustained meditation practice and doctrinal study. There’s no time for iconoclasm.”

Realizing that most Westerners understood Zen only through its texts and not through its living tradition, Buswell focused his scholarship on Buddhism as it’s actually practiced: “I felt that people needed to understand what life is like on the ground in Zen monasteries—what monks are actually doing rather than what they say they’re doing.”

With this aim in mind, he published The Zen Monastic Experience: Buddhist Practice in Contemporary Korea (1993), which provides a rare glimpse into the day-to-day of monastic life as he encountered it at Songgwang-sa. Through examining the rigors of monastic training, the delicate interplay between doctrinal study and meditative practice, and the practicalities of life at a monastery, the book provides a counterparadigm to many Western stereotypes about Zen.

In 1986, Buswell was hired as an assistant professor in the Department of Asian Languages and Cultures at UCLA. Though he was ostensibly appointed to teach courses in Chinese Buddhism, he believed the department viewed him as someone who could look across traditions and begin to build a program in Korean studies—and Korean Buddhism in particular. “I think they saw in me someone who could articulate a vision of what that program could become,” he said in a recent interview with UCLA.

When he first arrived at the university, there were no courses that covered Korean language and culture (and no faculty to teach them). Yet demand for opportunities to study Korea was “exploding”: the Korean American student population was growing rapidly, and the first tremors of the Korean Wave left many others interested in Korean history. Responding to this rising interest, Buswell developed a vision for what a program in Korean studies might look like.

While most existing programs prioritized studying contemporary Korea, Buswell proposed that UCLA first focus on premodern Korea to provide a deeper understanding of the nation’s history and place within the broader East Asian cultural context. “Because they used literary Chinese as their lingua franca, Koreans were able to communicate across national boundaries throughout their history,” Buswell says. “Korea was deeply embedded in Chinese and Japanese Buddhism, so focusing on premodern Korea allowed us to demonstrate the synergies with Chinese and Japanese studies and to highlight Korea’s centrality in the broader East Asian tradition.”

In Buswell’s first few years at UCLA, he helped to recruit a number of faculty members to build up the department’s Korean studies curriculum: Peter H. Lee, a senior scholar of Korean literature; Sung-Ock Sohn, an instructor in Korean language and linguistics; and John Duncan, a scholar of Korean history and Confucianism. With these core faculty members, they established a small graduate program focused on premodern Korea with the intention to expand over time.

In 1993, at the encouragement of the UCLA administration, Buswell drafted a proposal to establish a Center for Korean Studies. He approached the newly formed Korea Foundation for funding. At the time, the Korea Foundation was looking for opportunities to strengthen international ties and bolster global cultural literacy about Korea. With the Korea Foundation’s support, the Center for Korean Studies was able to establish faculty positions in humanities, social sciences, and art history, as well as a permanent librarian for Korean materials. These new positions established the Center as the largest program in Korean studies in the country. With this institutional support, the program was also able to add an undergraduate major in Korean language and culture, which quickly gained traction among students and has only grown in popularity since then.

The Center for Korean Studies was instrumental in establishing Korea’s importance in the academic study of Buddhism. “Robert put Korea on the map—and kept it on the map,” says Richard McBride, Professor of Korean and Buddhist Studies at Brigham Young University and Buswell’s first doctoral student. But his contributions to Buddhist studies extend beyond Korean Buddhism. “Robert Buswell is duly famous for almost single-handedly establishing the study of Korean Buddhism in the North American academy,” says Donald S. Lopez Jr., the Arthur E. Link Distinguished University Professor of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies at the University of Michigan and Buswell’s longtime collaborator. “But he is also one of the most accomplished American Buddhologists of my generation, doing sophisticated work in everything from Sanskrit Abhidharma to Chinese Buddhist apocrypha.”

With the Center for Korean Studies well under way, Buswell turned his attention again to Buddhist studies, going “back to [his] roots,” with the hopes of establishing a similar program. As with Korean studies, he began by advocating for building up the faculty. The Department of Asian Languages and Cultures had recently hired a scholar of Japanese Buddhism, but Buswell noticed a lack of emphasis on Indian and South Asian traditions. To fill this gap, he helped recruit Gregory Schopen, an eminent scholar of Indian Buddhism.

As the core faculty in Buddhist studies grew, the administration asked Buswell to put together a formal proposal for another center. In 2000, UCLA established the Center for Buddhist Studies, which receives substantial support from the Numata Foundation. “I don’t think there was another Buddhist studies research center in the country at that time,” Buswell told Tricycle. “It really was the first of its kind.”

At the heart of Buswell’s vision for the center was collaboration across disciplines. In addition to faculty in Buddhist studies, the Center draws together scholars in anthropology, art history, archaeology, neuroscience, medicine, and more. Jennifer Jung-Kim, the current assistant director of the Center, notes that the Center has always aimed to bring people together across campus. “That interaction with scholars across disciplines enriches everyone, both within and beyond Buddhist studies,” she told Tricycle.

One of Buswell’s first tasks as director of the Center was overseeing Macmillan’s two-volume Encyclopedia of Buddhism (2004). He and his colleagues at the Center brought in scholars from around the world to assemble a 500-entry encyclopedia that quickly became a reference work for graduate students and professors alike. Nearly a decade later, Buswell and Donald Lopez produced the 1.2-million-word Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (2013), with more than 5,000 entries compiled with the help of graduate students at UCLA and Michigan.

“Buswell and Lopez’s Dictionary of Buddhism profoundly transformed how I understand, cross-reference, and translate Buddhist terminology from the primary canonical languages,” says Frederick M. Ranallo-Higgins, Tricycle associate editor and a former student of Buswell’s. “Even here at Tricycle, we have multiple copies and frequently reference it as a reliable authority.”

The Center has also supported Buswell’s efforts to make classic Korean texts more widely available, both in Korea and in the US. Many of these projects go beyond the texts that scholars typically privilege and instead center on the materials that monks actually use, including apocryphal texts, ritual materials, and monastic curricula.

The first major translation project Buswell spearheaded was the thirteen-volume Collected Works of Korean Buddhism, the first comprehensive collection of Korean Buddhist materials ever to be published in a European language. The anthology spans two millennia of texts, including commentaries on scriptures, collections of kongan (koan) cases, travelogues and diaries, and historical materials, and aims to give the writings of Korean Buddhist masters “their rightful place in the developing English canon of Buddhist materials.” The Chogye Order distributed the series to monasteries throughout Korea for everyday use, and it is freely available online on the website of the Center for Buddhist Studies.

Buswell has also served as an editor for the Korean Classics Library, a sixteen-volume series of classic Korean religious and philosophical texts. Many of the texts in the series have never been published in any language, even modern Korean.

One of the largest translation efforts he has supported is that of the Tripitaka Koreana, a 13th-century collection comprising 81,257 woodblocks. Lauded as the most complete and accurate extant collection of Buddhist texts, the collection contains the Tripitaka, or “three baskets,” as well as Sanskrit and Chinese dictionaries, travelogues, and diaries and biographies of monks and nuns. Buswell has advocated for renaming the collection the Korean Buddhist Canon to reflect its broader scope—and to demonstrate Korea’s central role in the development and preservation of key Buddhist texts. “In Korea, Robert is well-known and respected even by the nonacademic community because of how he has championed awareness of this Korean national treasure,” Jung-Kim says.

These projects illustrate Buswell’s commitment to maintaining ties with Korean academic and monastic communities, as well as his aspiration to demonstrate what Korean Buddhism has to offer to the field of Buddhist studies. In 2009, he was asked to help establish an international research center for Buddhist studies at Dongguk University, a Buddhist-affiliated university in Seoul. For three years, he served as the founding director of the Dongguk Institute for Buddhist Studies Research while also maintaining his position at UCLA, and he used this unique dual role to bridge the divide between Buddhist studies in Korea and in the US.

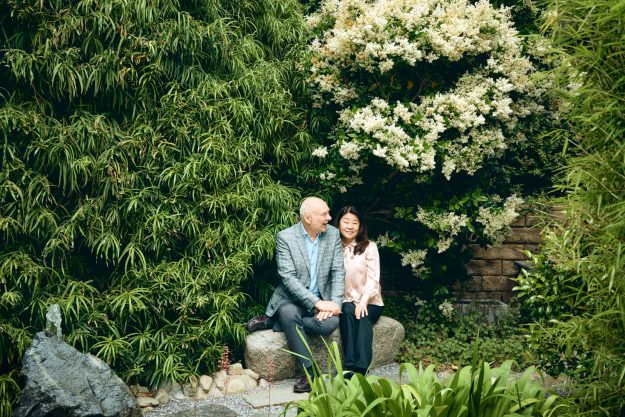

At the encouragement of his wife, Christina, Buswell organized a number of conferences at Dongguk, bringing both Korean and Western scholars into dialogue with Korean monastic teachers. “In Korea, most monks still live in the mountains, and most scholars live in the cities, so there aren’t a lot of opportunities for conversation,” Buswell noted. In fact, for some of the monks, it was their first time setting foot in the university.

Most of the scholars at the conferences had never been to a monastery before either, so Buswell also arranged tours and retreats so that they could observe and participate in everyday monastic life. “That way, they could see what it really means to embody the Son tradition,” Buswell says.

Buswell brought this same spirit of collaboration to his teaching and advising. Over the course of his time at UCLA, he supervised nineteen PhD students, many of whom have gone on to shape the field of Buddhist studies. George Keyworth, associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan and one of Buswell’s first doctoral students, jokes that it’s hard to identify a Buswell student because of how wide-ranging their research areas are—he encouraged students to find topics and methodologies that were of interest to them, even if these areas were outside his own expertise. These topics are far-reaching, ranging from spontaneous human combustion and self-immolation to the role of tea and alcohol in medieval China to the history of Buddhist spells and incantations.

“I’ll miss having regular exposure to students—the chance to come out of my study for a while and just talk about Buddhism.”

“He wanted us to find new directions, places where we could make a contribution to the larger field of Buddhist studies,” says James Benn, Professor of Buddhism and East Asian Religions at McMaster University and one of Buswell’s first students. “He treated students in his seminars as scholars of the future.”

Keyworth agrees. “He was extremely supportive, and the biggest thing he taught us was to get out there to build the field and promote the study of Buddhism.”

Buswell remained at UCLA for thirty-six years, continuing to teach the next generation of scholars until his retirement in June 2022. “He spent basically all his career at UCLA, which demonstrates his commitment to the kinds of education that can take place in a public university,” Benn remarked. “A lot of Buddhist studies goes on at the Stanfords and Harvards and Princetons of the world, but Robert was a strong believer that Buddhist studies had every reason to be at big state schools as well—and that the scholarship that takes place in public institutions should inform Buddhist studies globally.”

Part of Buswell’s commitment to public institutions manifests in his dedication to teaching undergraduates, particularly in introductory courses. He describes the Introduction to Buddhism course as his favorite class precisely because of the variety of backgrounds and experiences that students bring to the course. “Some students come in with little to no understanding of Buddhist teaching and practices,” he says, “so that’s where it’s possible to frame their understanding of the tradition and what it can offer us today.”

As he looks ahead, Buswell cites talking with students as what he will miss the most. “I’ll miss having regular exposure to students—the chance to come out of my study for a while and just talk about Buddhism.”

Even in retirement, though, Buswell continues to advocate for the place of Buddhist studies at UCLA and to lay the foundation for future generations of scholarship. In May 2022, he and Christina made gift commitments of $3.7 million to establish the Chinul Endowed Chair in Korean Buddhist Studies and the Robert E. and Christina L. Buswell Fellowship in Buddhist Studies. The endowed chair, named for the monk Buswell has dedicated much of his life to studying, is the first permanent endowed chair in Korean Buddhism outside of Korea.

Buswell said in a press release that it seemed appropriate to name the chair after Chinul because of his broad impact on the trajectory of Korean Buddhism, particularly his synthesis of meditation and doctrine: “Chinul believed that success in Buddhist meditation demanded a solid grounding in doctrinal understanding. This rigorous combination of doctrinal study and Zen meditation has remained the distinguishing characteristic of Korean Buddhism ever since.”

For many of his students, his retirement is bittersweet; it’s hard for them to imagine UCLA without him. “The Center is where it is today because of Robert’s vision,” Jung-Kim reflects. “We’ll feel his presence for a long time.”

He will be missed not only for his many contributions to Korean and Buddhist studies but also for the spirit of generosity and humility he brings to his work, which his students and colleagues cite as a rare gift.

“His distinguishing feature is his kindness, which is not always the case in academia,” Benn comments. “Sometimes, people with high scholarly standards have been taught to be rigorous in their professional life, so they bring a degree of rigor and harshness to their personal interactions as well. But not Robert. He’s very patient, and he’s a good listener, which can be unusual for senior figures in the field—he doesn’t always want to be the person talking.”

“I think it has to do with his training as a monk,” Keyworth adds. “He never lost sight of that side of his life, personally or professionally. I don’t think there’s another academic like him, and I don’t know that there ever will be.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.