The Search for the Panchen Lama

By Isabel Hiltion

W.W. Norton and Co., 2000

336 pp.; $25.95 (cloth)

In 1996 I was sent by Vanity Fair to Dharamsala, India, to interview the Dalai Lama about the abduction of the six-year-old Eleventh Panchen Lama by the Chinese government, and there I met Isabel Hilton, who was directing a documentary on the tragedy for the BBC Ms. Hilton had already won my admiration seven years earlier for her interview with Paraguay’s ousted generalissimo Alfredo Stroessner—an interview I had failed to get two months before. She had just come from Beijing, where she had gotten to see the Tenth Panchen Lama’s Chinese widow, Li Jei—another coup. That was because, as one learns from her important book, Ms. Hilton lived in Beijing in the seventies and speaks Chinese and knows how to navigate the Communist bureaucracy. Indeed, her understanding of the Chinese side of the story is what she most brings to this project—a perspective and expertise sadly lacking in most writers on Tibet (the reviewer included).

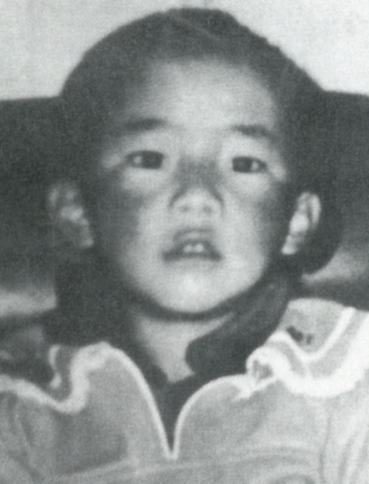

I watched a pro at work as Ms. Hilton directed the filming of a monk demonstrating the tsampa ball divination, one of the means by which the Dalai Lama confirmed that Gedhun Choekyi Nyima was the eleventh incarnation of the Panchen Lama. (Balls of barley flour, each containing the name of a candidate, are rotated in a bowl until one jumps out.) The Dalai Lama was impressed by Ms. Hilton when they met in 1994, and agreed to let her in on the progress of the secret search For the new Panchen Lama, which was still going on. The Tenth had been dead since 1989. His life had been a tragic, controversial, and ultimately heroic one. A massive man, he had endured torture and years of solitary confinement by the Chinese, only to die mysteriously at the age of 50, at the moment of his rehabilition among Tibetans and triumphant return to his monastery, Tashilhunpo, in the city of Shigatse. Many suspect that he was poisoned by agents of Beijing.

The second highest hierarch in the Gelugpa sect, the Panchen Lama is rook to the Dalai Lama’s queen. Lacking the Dalai Lama’s political base, he has historically been more open to the overtures of foreigner, like the English and the Chinese Ms. Hilton ably traces his ambivalent role in Tibetan history and his brotherly but increasingly conflicted relationship with the Dalai Lama through their various incarnations. She chronicles the search for the Eleventh Panchen in all of its Florentine complexity, how the Chinese ended up rejecting Choekyi Nyima because he was the Dalai Lama’s choice, and installed their own “soul boy,” Gyaltsen Norbu, spuriously claiming that the Panchen was traditionally identified by a lot drawn from a golden bown by the Chinese ambam, the representative to Tibet of their Manchu predecessors (this did happen a few times, when the urn was used to break a stalemate among candidates, but the ultimate arbiter of process has always been the Dalai Lama). No one has seen Choekyi Nyima or his parents since they were taken from their home in the province of Nagchu and whisked off in a plane a few weeks after the Dalai Lama’s announcement on May 14, 1995, that he was the new Panchen. Chadral Rimpoche, the acting head of Tashilhunpo who secretly collaborated with the Dalai Lama in the search, is serving six years in prison for being a “splittist.” The false Chinese soul boy is being brought up and indoctrinated in a villa outside Beijing. He has made one appearance, under heavy guard, in Tashilhunpo. Whether he ever takes up residence there and what Tibetans’ reactions would be if he did remains to be seen. But as Ms. Hilton concludes, the fact that the succession to the second highest religious office in Tibet is now controlled by the Chinese does not bode well for the future of the Dalai Lamaship, whose next incarnation will in all probability be appearing in the next few decades.

The unresolved tragedy of the Eleventh Panchen Lama is off the radar even of Tibet-watchers, which is why Ms. Hilton’s book is so welcome. But the situation is not, except for China’s input, untypical. Intrigue and treachery, rival factions and power plays have often attended the recognition of high tulkus, who often had monasteries and considerable wealth attached to their lineage. Currently there are two rival claimants for the 17th Karmapaship, and this equally byzantine drama—which has heated up with the escape last year from Tibet of one of them, Ugen Thinley, from Tibet—has eclipsed the Panchen Lama’s on Western screens. The Karmapa is the head of the Kagyupa sect, which predates the Gelugpas and has a stronger presence in Europe and North America, so there is a lot riding on the outcome of the Karmapa question, particularly in the West, where the Kagyupa congregation is bitterly divided over the two boys. I met both of them on the same trip that I met Ms. Hilton—Ugen Thinley at Tsurphu, the Karmapa’s hereditary seat at the head of a breathtaking glacier-plugged valley three hours from Lhasa, and Tenzin Chentse, who is the protege of Shamar Rinpoche, at his monastery in New Delhi. Ugen Thinley, then twelve, was surrounded by Chinese security people and all I was able to do was prostrate and present my khata. He was actually reading a comic book, and when I paused at the door to take a last look at him, he winked at me, and the effect was zapping, as when the Dalai Lama once gave my beard a playful tug.

It’s puzzling that Isabel Hilton did not visit the Karmapa boys, and I think her book would have benefited from more discussion of their case. I personally would have liked to see more on the theology and mechanics of reincarnation, because it seems to me that not only the Dalai and Panchen Lamas, but also the entire belief system on which this mystical society depends, is threatened. But Ms. Hilton, however sympathetic she is to the Tibetan cause, remains skeptical about the whole process, perhaps because of all the corruption and un-Buddha-like behavior it has engendered. She doesn’t mention the very interesting belief that a tulku can have more than one incarnation. As the Dalai Lama explained to me on that same trip, “two separate emanations from the same source can exist. There are several kinds of reincarnation: (1) the previous self takes a new body. (2) the ultimate source of the reincarnation can multiply simultaneously, so in that case recognition may not necessarily come after previous death. Two reincarnations can happen. For instance, there are two of Taklun Tsetul, one in central Tibet, the other in eastern.”

In the case of the Karmapa, he went on: “If Shamar has authentic indications about his own candidate it is possible that he [Tenzin Chentse] is an authentic manifestation.” The problem remains, however, that there can be only one throneholder. As the Dalai Lama put it to Situ Rinpoche, the main backer of Ugen Thinley, “two people can’t sit in the same chair,” and the Dalai Lama has recognized Ugen as the throneholder—not that he has any jurisdiction over Kagyu tulkus, but h is blessing is importan t for world opinion. The option remains of declaring Thinley an octul, a sort of runner-up Karmapa who is not a complete mind-body-sould manifestation and who, like a dominant gene with imperfect penetrance, did not get enough of the Sixteenth Karmapa’s characteristics to inherit the throne.

There are, in fact (which Ms. Hilton does not mention) two oetüls of the Tenth Panchen Lama, both of whom are in their fifties and live in India. Even more interesting, the Tenth Panchen (who was enthroned in 1952 and was the third choice, after two other boys died), was actually born several months before the Ninth died. When I asked the Dalai Lama how this was possible, he explained that the Tenth Panchen was an example of the second type of reincarnation. Ms. Hilton writes that reincarnation requires, “like gestation,” nine months after the death of the previous incarnate to transpire. But the relationship between the times of death and rebirth seem to be much more fluid.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.