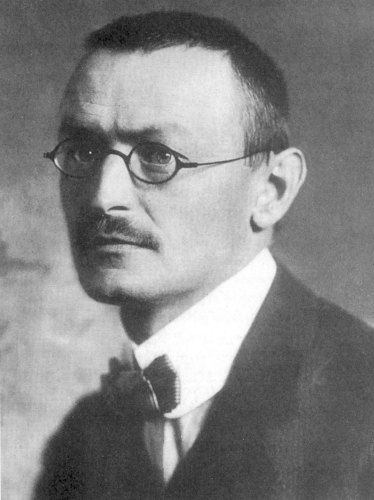

I have not only occasionally made a confession of belief in essays, but once, a little more than ten years ago, attempted to set forth my belief in a book. This book is called Siddhartha.

—Hermann Hesse, “My Belief,” 1931

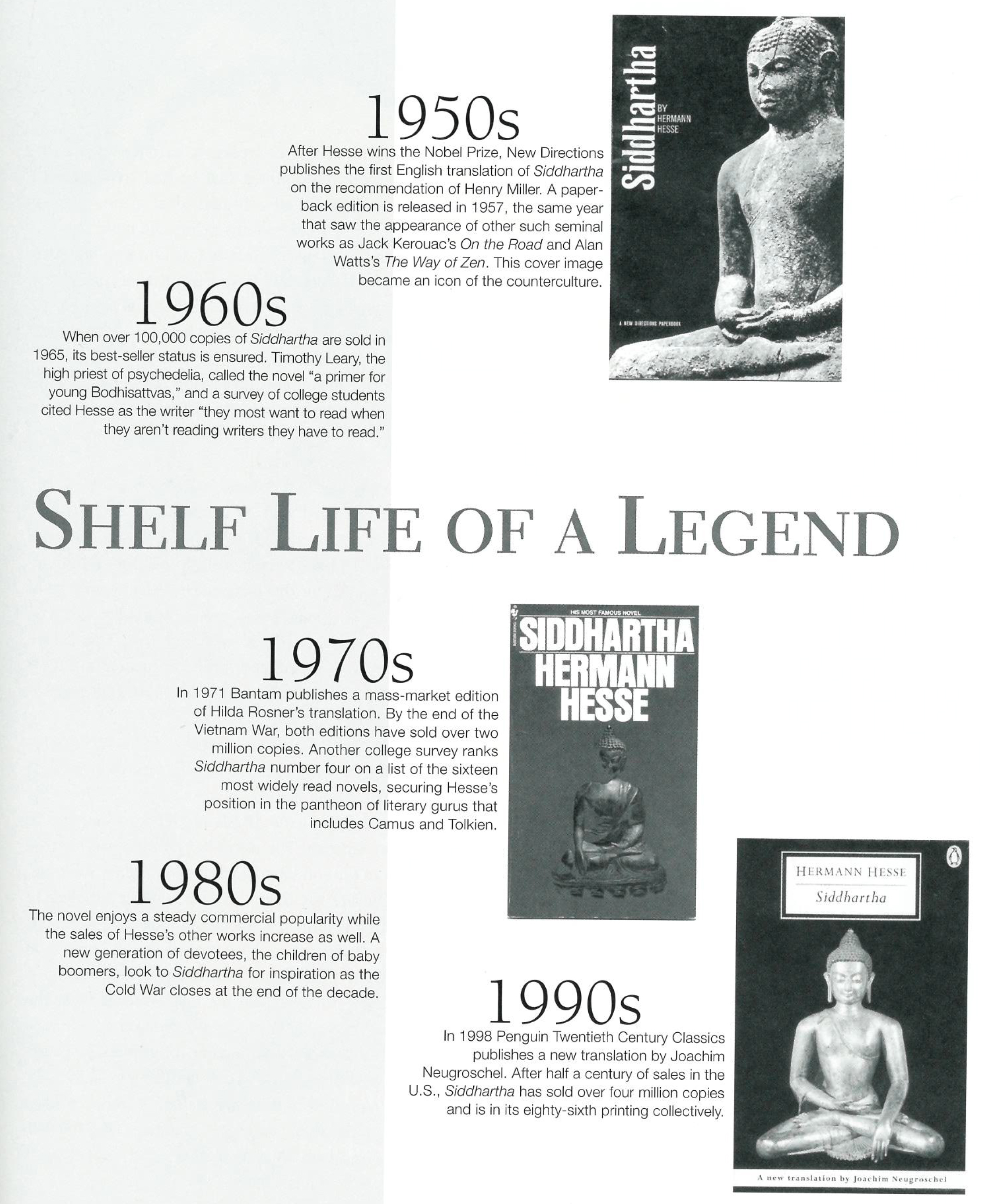

When New Directions decided to publish the first English translation of Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha in 1951, it could not have foreseen the enormous impact it would have on American culture. The novel’s ostensibly simple narrative—the story of a young, accomplished Brahmin, Siddhartha, who defies his father’s tradition in favor of wandering India in search of enlightenment— appealed to the restless drifter, the alienated youth, and the political anarchist alike. Its many motifs include the outcast from society; rejection of authority; communion with nature; recalcitrance toward schooling; and the idea of an immanent God. Published in the U.S. during the Cold War, Siddhartha addressed a perennial unrest and provided a new set of values for a generation of young people disenchanted with their parents’ conservatism. By the author’s own admission, Siddhartha is a story about individuality and self-expression, a quintessential Western tale cloaked in Indian garb and punctuated with a staunch nonconformity that served to cross both generations and cultures.

Despite Hesse’s eclectic interest in the world’s religions, no other spiritual discipline permeated his entire life more than Buddhism. Many of his novels were infused with its compassionate foundation, while his characters became centered through developing an awareness of themselves and their own behavior with a kind of mindfulness that transcended the intellectual content of Buddhist philosophy. The author was struck by the Buddha’s “life as lived, as labor accomplished and action carried out. A training, a spiritual self-training of the highest order.” It is this discipline which we see reflected in Hesse’s writing and in his own psychological struggle.

His most influential work, Siddhartha is arguably also his most optimistic. The novel offered its readers hope for liberation in this lifetime, a hope that was absent from both the German and the American youth movements that had surfaced in the wake of two world wars. There could not have been a more encouraging message available to those who sought the “Way Within.” As a result, America witnessed a Hesse phenomenon that was unparalleled for a European writer. And yet despite its seemingly preordained success in America, the odds seemed stacked against the novel ever being finished in the first place back in 1920. It was only through a series of transformative experiences, wherein the author reinvented himself, thatSiddhartha was born. Indeed, the novel had a legacy all its own prior to its arrival on American soil; the author’s process of self-realization was inextricably tied to the composition of the novel itself.

In 1918, a year and a half before he would begin work on his Indian legend, Hermann Hesse awoke from a dream one rainy morning in Bern, Germany. He lay motionless in a quasi-dream state, not yet awake enough to look at his clock, and slowly ascended from layers of sleep to become aware of his surroundings. His head ached as he looked around his room, noticing the way the light fell on his clothes draped over a chair, the play of shapes concealed in the mist that rolled past his window. He longed to fall back to sleep, but as he heard the rain falling softly on the roof, he was filled with great sadness and pain; the memory of a long dream sequence had emerged with him from his slumber like a shadow. Hesse would later relate the dream in his diary – how he had heard two voices, both of which spoke to him of a profound sorrow, but it was the second voice, the deeper and more resonant of the two, that commanded: “Listen to me! Listen to me, and remember: suffering is nothing, suffering is illusion. Only you yourself create it, only you cause yourself pain!”

After contemplating the dream’s meaning, he described the second voice, saying it “was itself dark, it was itself primal cause.” That Hesse should dwell so intently on a dream is no surprise: As early as 1916, following the second of several nervous breakdowns, he had undergone psychoanalysis with a therapist and disciple of Carl G. Jung (and would benefit later from a close rapport with the prominent psychologist himself). Hesse was well acquainted with Jung’s notion that the unconscious could access states of awareness available to the whole of humanity. He knew that this voice was a response to the fundamental question of existence that had been hounding him since childhood.

Until then, Hesse’s entire life had been a series of rebellions, from his dropping out of school at the age of thirteen, to his break with the tradition of his Protestant parents and their hope that he follow their missionary ambitions, to his fierce opposition to the global conflict of World War I. His grandfather, who was proficient in nine Indian languages and who was widely acknowledged throughout Europe as an authority on the subcontinent, encouraged the young Hesse’s appreciation for the spiritual classics, which led to the author’s realization “that not only East and West, not only Europe and Asia are unities, but that there is a unity and an association over and beyond that – humanity.” It was his grandfather’s love of India that convinced Hesse, a decade after his mentor’s death, to travel there in 1911 in an attempt to reconcile his family’s tradition of missioning with his own rebellious spirit. His exposure to Indic culture, and to Buddhism in particular, would color much of his later work, but the experience of his journey to the East did not satisfy his spiritual longing.

In 1919, Hesse sought solace and escaped to Montagnola, a town in the foothills of the southern Swiss Alps, in a small village where he would reside for the rest of his life. Although his colleagues teased him that he had become a monk, Hesse felt he had finally succeeded in achieving what he had yearned for years earlier when, at the height of his restlessness as a husband and father, he had proclaimed: “I would give my left hand if I could again be a poor happy bachelor and own nothing but twenty books, a second pair of boots, and a box full of secretly composed poems.” However, his newfound independence had a greater price than mere corporeal sacrifice: Forced to commit his wife to an asylum after her rapid descent into schizophrenia, he was unable to provide for his three sons and regretfully placed them in the care of friends. It is clear from his correspondence during this year that both decisions weighed heavily upon his conscience. Yet, despite the emotional stress, Hesse emerged from his own period of crisis—during which time World War I had ended—to experience one of the most productive and creative years of his life. This significant shift in perspective was most evident in December 1919, when Hesse began composing Siddhartha. The writing came easily to him at first, and he completed Part One in the early months of 1920. Then, nothing.

In mid-1920, despondent, he wrote to a friend: “For many months my Indian ‘poem,’ my falcon, my sunflower, the hero of Siddhartha, lies fallow.” Unable to further advance the novel, he confessed to another friend that “my big Indian work isn’t ready yet and may never be. I’m setting it aside for now, because I would have to depict a next phase of development that I have not yet fully experienced myself.” This statement reveals the severity of Hesse’s existential plight. The initial chapters that comprise Part One are concerned with Siddhartha’s unrest, his questioning mind, from his refusal to follow the Brahmanical tradition of his father to the mendicant path of the wandering ascetics and ultimately to the contemplative way of the Buddha. These chapters had, according to Hesse, “proceeded splendidly,” informed by the author’s own suffering. But in order for Part Two to be successful, Hesse had to contend with the protagonist’s triumph, whereby Siddhartha finally attains enlightenment. Conceiving such a solution to his character’s suffering was impossible, however, as long as the author remained disassociated from his own inner being.

If not for Hesse’s unrelenting determination for self-discovery, Siddhartha surely would have been abandoned. In July 1921, this might have seemed to be the case when Part One was published independently without a proper ending. Through his close work with Jung during these years, Hesse confronted his dislocation from society to complete his own journey while Siddhartha remained adrift. With Jung, Hesse revisited his childhood, a childhood filled with Indian antiquities set against the backdrop of Christian iconography. He re-immersed himself in the world’s sacred literature which he had first encountered as a child in his grandfather’s library. And he discovered an appreciation for the teachings of the Buddha. Of course, Hesse’s sympathy for Buddhism was not solely responsible for his eventual catharsis; Buddhist thought had been just one component of his general awareness of the Asian religions that were in vogue at that time. But the influence that the Buddha’s teachings had on the writing ofSiddhartha is unmistakable.

Early in 1921, Hesse wrote to an artist friend of how Buddhism had been his “sole source of consolation” for years, and although he admitted that “gradually my attitude changed, and I’m no longer a Buddhist,” he acknowledged the benefits of Buddhist practice later that year:

The point and goal of meditation is not knowledge in the sense of our Western intellectuality but an alteration of consciousness, a technique whose highest result is pure harmony, a simultaneous and equal cooperation of logical intuitive thinking.

As he grew more familiar with Buddhist doctrine, Hesse began to understand the subtleties of practice that moved him out of his acute depression. For him, the speeches of the Buddha were “a source and mine of quite unparalleled richness and depth,” he wrote in his diary. He continued:

As soon as we cease to regard Buddha’s teaching simply intellectually and acquiesce with a certain sympathy in the age-old Eastern concept of unity, if we allow Buddha to speak to us as vision, as image, as the awakened one, the perfect one, we find in him, almost independently of the philosophic content and dogmatic kernel of his teaching, a great prototype of mankind. Whoever attentively reads a small number of the countless “speeches” of Buddha is soon aware of a harmony in them, a quietude of soul, a smiling transcendence, a totally unshakable firmness, but also invariable kindness, endless patience.

Resuming work on the novel in early 1922, he quickly completed the eight chapters that comprise Part Two. By May of that year, it was finished: Hesse’s Siddhartha—whose name in Sanskrit means “he who has found the goal”—comes to rest in a middle way just as Hesse himself discovers his own way out of depression. The author’s understanding of Buddhism has its finest expression toward the end of the novel, when Siddhartha quietly meditates on the movement of the river: “He had died and a new Siddhartha had awakened from his sleep. He also would grow old and die. Siddhartha was transitory, all forms were transitory.” Finally, in October of 1922, the novel was published in its entirety.

Hesse was not completely satisfied with the finished work; he doubted that he had “reformulated for our era a meditative Indian ideal of how to live one’s life.” But a few months before the novel’s publication, an Indian professor from Calcutta who had seen the finished work impressed upon the author the imperative that Siddhartha “be translated in all European languages, for here we face for the first time the real East presented to the West.” Encouraged, Hesse wrote to a friend expressing his hope that the novel appear in English, “not for the sake of the English themselves but for those Asians and others whom it would vindicate.”

As early as 1925, the first translation into Japanese appeared, followed later by editions into many Indian languages during the fifties. And though a Chinese translation did not appear until 1968, the enormous demand in Asia for this imaginative Indian tale is testament to the universal truth which Hesse had apprehended. Contented with the reception of his lyrical novel, Hesse never returned to India as a literary device, but his appreciation for the Buddha’s teachings did not wane.

Hesse said of sacred literature: “The very oldest works age the least.” This sentiment may be applied toSiddhartha as well, for it is as fresh as ever, still relevant today as it was in the 1920s Germany and in the 1960s in America. The novel has journeyed through a century of turmoil bearing witness to human suffering. A year before his death in 1962, while Siddhartha climbed to commercial success in the U.S., the author described how one of the “simple and immediately impressive” Zen koans struck him as a revelation: “[It] overcame me like a breath from the universe, I experienced an ecstasy and at the same time a terror as in those rare moments of immediate awareness of experience which I call ‘awakening.’” Similarly, Siddharthaserved in koan-like fashion to wake millions from their delusions, to inspire, challenge, and remind, as Hesse’s dream-voice had done, that “suffering is nothing, suffering is illusion.”

Click on the image to enlarge.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.