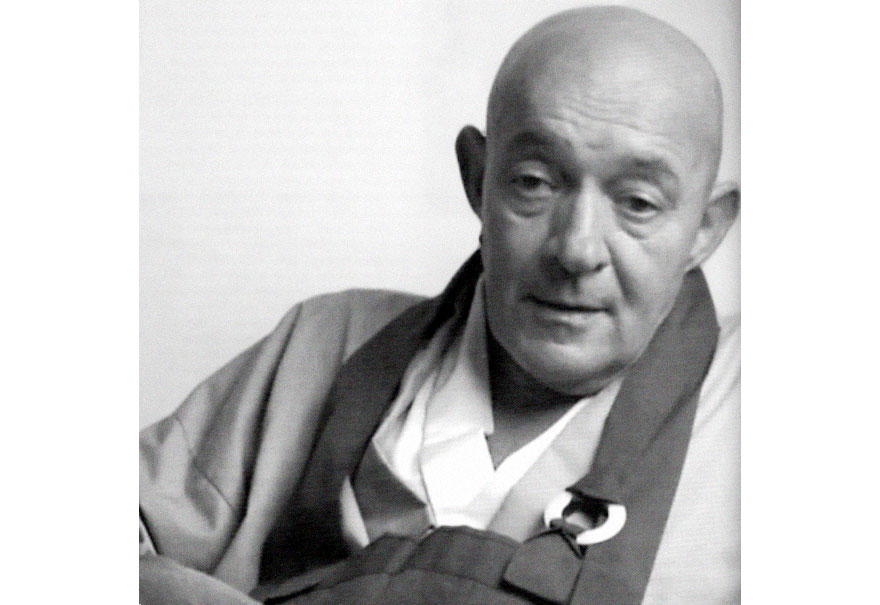

John Daido Loori is the abbot of Zen Mountain Monastery (ZMM) in Mt. Tremper, New York. He is a Dharma heir of Hakyu Taizan Maesumi Roshi, founder of the White Plum Asanga, and has received transmission in both the Rinzai and Soto lines of Zen. Daido Loori is also founder and director of the Mountain and Rivers Order, an organization of Zen Buddhist temples, practice centers, and sitting groups in the United States and abroad. In addition, he is president of Dharma Communications, which promotes Buddhist teachings through videos, audiotapes, meditation supplies, Mountain Record quarterly, and Internet activities. Under his guidance, ZMM has established a Zen Environmental Studies Center and engages in an array of social action programs for, among others, prisoners, the homeless, and people with AIDS. This interview was conducted in Daido Loori’s office at ZMM, photographs by Stuart Soshin Gray. Interview by Jeff Zaleski.

In December, you’re giving a course at Zen Mountain Monastery on the “Vows for the New Millennium.” This year, you’ve offered “Zen Teachings for a New Millennium” at the Smithsonian Institute and throughout the country. What does the millennium mean to you? In a sense, it’s a millennium because by agreement we make it a millennium within our particular calendar. But because it seems important to people all over the world, it becomes an opportunity to teach. As a teacher, one aspect of my job is to seize opportunities like this and use them to bring focus and awareness to our vows, morality, and ways in which we can improve the lot of people who are suffering all over the world.

Are your teachings for a new millennium different than your teachings for the old millennium? Of course not. The teachings are basically a moment-to-moment nonstop flow; each breath follows the previous one. Yesterday it was like that; today is like that; tomorrow will be like that.

In the catalog description of your workshop on the vows for the new millennium, you mention “complexities and challenges of the twenty-first century.” What are the particular challenges facing Buddhism as we enter into this new millennium? I really feel that Buddhism has something very special to offer. I think that understanding the nature of the universe and the nature of the self from the Buddhist perspective can help us take care of many of the problems in this world if enough people are practicing. I think that we need to address our relationship with the environment, population explosion, hunger, and peaceful coexistence. Buddhism is equipped to deal with these issues. The Flower Garland Sutra describes the universe as a net of diamonds that exists in three-dimensional space and in the fourth dimension of time. It goes backward and forward in time. Every diamond in this net is multifaceted and reflects every other diamond in the net. When you see one diamond, you actually see every other diamond in the net. You see the whole thing. Nothing is left out of the picture. When you touch one diamond, you’ve touched every diamond in the net. It’s incomprehensible that each thing contains every other thing, that there’s a mutual identity and causality, that each thing contains the totality of the universe. But that’s the nature of reality.

Those are nifty ideas and they sound right, but what does that mean for me sitting in this chair here? How does it work on a personal level? This is where practice becomes indispensable. All of the teachings are an abstraction to the listener. Some of it’s not even logical. This morning I talked to my students about formless form. What is formless form? Those are contradictory terms. It’s a paradox. The phrase doesn’t make sense. It is an intuitive and intimate realization; that’s why you can’t explain it to somebody. That’s why practice is so important. Each person needs to see it for themselves. There’s a skillful process and the process says to “take a backward step.” Go very deep into yourself. Let body and mind fall away. Experience the absolute basis of reality. But the path doesn’t end there. This is just the peak of the mountain. You need to continue the journey. Where do you go when you’re at the peak? Straight ahead. It’s always straight ahead. Straight ahead when you’re on the peak means down the other side of the mountain back into the marketplace. That’s where your realization needs to manifest. Otherwise, what’s the point? It surely isn’t to spend our lives contemplating our navels on a 245-acre monastery hidden in these mountains. It’s got to do with manifestation in the world. Realization needs to be actualized. And having realized the fact that there’s no separation, an imperative arises to reach out to take care of things. That’s compassion. We take care of things because everything is this very body and mind itself. What we take care of is another question.

Is that the challenge for Buddhism at this point, to really figure out what to take care of? I don’t think that you can determine that precisely in terms of the institution of Buddhism. The point of view of the institution of Buddhism is to take care of it all. When we get down to each individual Buddhist, each person needs to look at their own resources, power, position in life, commitment; how much are they willing to do?

Let’s talk a little bit about this monastery and the way that you practice Zen here in these mountains. You’re a Japanese lineage, and you’re in the middle of the Catskills. You walk around the monastery in Japanese robes. Yet, you don’t seem to be involved in what I call American Buddhism. You’re really an authentic model of Japanese Zen. I would disagree. A lot of people think that—except the Japanese. When the Japanese come here and see what we’re doing, they call it “cowboy Zen.” Many of the forms and trappings that seem exotic or foreign have to do with the fact that this is a monastic setting. If you were to enter a Trappist monastery, you might feel equally estranged by their exotic forms and rigorous discipline.

What role do you think monasticism will play in American Buddhism in the upcoming century? It will be pivotal. Until deep monastic roots are established on American soil, Buddhism will not fully have arrived here. Ten years ago, at one of the Buddhism and psychotherapy conferences, somebody on the panel said, “There is no model for monasticism in the West.” In a single stroke they wiped out centuries of Christian monasticism. There’s definitely a model and a place for monasticism in Christianity and in western Buddhism. It’s not going to be popular. It never was popular, even during the golden age of Zen. It doesn’t need to be. Zen training is very demanding. Monasticism is the core of this practice tradition. It shows that it’s possible to do this all-out. The monastics here dedicate their lives to the Dharma: seven-day sesshins every month, sitting every morning and night, year after year after year. They maintain the archive of sanity and serve the sangha. The rest of our sangha comes into the monastery to recreate themselves and then brings their practice back out into the world. And it definitely affects their lives and how they do the things that they do, the ten thousand things they do—teaching, mothering, doctoring, loving, working. There is an interdependent relationship between lay practice and monastic practice. The monastic role will always be important.

I found a wonderfully provocative statement of yours that I’m going to read back to you. It’s from one of your commentaries on a koan: “There are hundreds of Buddhist centers throughout the country and hundreds of teachers but very little real Buddhism.” What is real Buddhism? Essentially, I’m talking about authenticated teachers. There are very few teachers in this country who are authenticated by their teacher. There are many self-styled and self-appointed teachers. Much of what we have in North America is a self-styled Buddhism, and it’s easy to sell style when you have not come out of twenty or thirty years of training. You don’t know the difference between the baby and the bathwater. It’s easy to miss and dismiss important dimensions of practice. I think that the more training a teacher has the more clarity they develop and the more cautious they are about making changes too swiftly.

One of the things that you have maintained here is hierarchy, and there’s no doubt who’s in charge, and that’s you. I saw a film of a Dharma combat you had with your students, and you were literally sitting on a pedestal What’s that about? What you are calling a pedestal is the “high seat,” common to almost all schools of Buddhism and indeed most religions. What I was sitting on was a ten-inch-high platform, a compromised version of the traditional high seat, which is three feet high. We have one of those also; it is kept in the corner of the room and has only been used twice in the past twenty years for special ceremonies. Hierarchy is a fact of life. Whether you like it or not, you have to deal with it all the time.

We only like it when we’re up in the hierarchy. Exactly. And we don’t like it toward the bottom. Most people are frightened by hierarchy, recoil from it, rebel against it, but never resolve the problem. Hierarchy is a convention. It’s there because we allow it. How do you learn to be free of it? In the context of practice, you deal with it within the hierarchy itself. You “use the entanglements to cut the entanglements.” We’re not going to solve the problems that arise within hierarchies by declaring that everything is equal. The face-to-face interviews in dokusan, the Dharma combat—they are set up in the traditional, hierarchical way. I’ve got an altar behind me, incense is burning, people prostrate themselves, come forward, and ask for the teachings. All the while my responsibility is to help them see their own inherent wisdom and power. There is an incredibly different way that the senior students deal with hierarchy from the way the beginning students do. Within the hierarchy, senior students have learned to trust themselves.

Still, there’s the idea that the guy on the pedestal knows the truth at every moment, and the student doesn’t know. And that isn’t the truth of it. You’re right. The person on the high seat doesn’t “know the truth at every moment”—not at all. Students inevitably do want to give their power away, and one of the things that the teacher does is to constantly throw it back at them.

How do you do that? By having them take responsibility. I’m not going to solve their problems. I have nothing to give them. There’s nothing to be given; there’s nothing to be received. And if a spiritual teacher says that they have something to give you, run for your life. You are dealing with a charlatan.

I would imagine that people constantly come to you looking for something. They want something from you. That’s the illusion. What I inevitably do is what my teacher did for me. Turn it back to them. Each one of us must realize our own power. In many religions, there is the tendency to surrender to a higher authority. That’s not the case in Zen. In the beginning of training it may seem so but, ultimately, the student needs to be free of the teacher, free of Buddhism, free of the whole catastrophe.

I question whether how much of what you’re saying applies when you move from your role as spiritual guide to your role of administrator. After all, it seems like the buck stops with you. According to the bylaws of our corporation, the spiritual leader is also the president of the corporation. At board meetings, if I take the chair, people are always trying to figure out what I want. So, someone else runs the meetings. I usually sit back. Usually I abstain from voting. The power is definitely there if I choose to use it. We also have a Board of Governors. I am not on that board. It consists of the representatives of the people we serve. It’s a group of about one hundred people that meets every few years over a weekend to develop a consensus about the future of the community. There are three other formal groups that have real power and make decisions. I’m not a member of any of them.

Do any of these groups ever actually contradict your wishes? Definitely. Recently they decided to expel a student. The student was a cause of a lot of disharmony. Well, you know, I have done similar things in my time. I had a soft spot for him and felt that we should cut him some slack. So I argued strongly in favor of the student being retained. I gave a pretty strong argument, but I also said I would honor their decision, and they decided to ask him to leave. I trust the individual and collective wisdom of these groups. They are, after all, my students.

[The following questions to Daido Loori are about his most innovative teaching vehicle: his vigorous exploitation of electronic communications, particularly the Internet, to spread the Dharma. We turn to his computer where he accesses a beta, or test, program, “Cyber Monastery,” a Zen training program that will be accessible only online. On the screen appears a list of requirements. The first two point to the future: “1. zafu. 2. IBM Pentium (computer).”]

Is this a secret site? Yeah, it’s not available to the public yet. I’ve got five of my seniors working on our new project for the last year and a half. It’s called Cyber Monastery, an online Zen training program. People will register and go through the same screening process that any student that comes here to practice has to go through. If they are accepted, they will enter the program. They will receive in the mail an interactive CD-ROM, and several video and audio tapes. The CD-ROM will contain links to the chat room. They’ll have an assigned training advisor who will be available for them in real time online for dialogues and discussions. There will be assignments, projects, and exams online, and the whole course will end with a traditional online Dharma combat with me.

Then what do they get? Enlightenment? [Laughter] What happens at the end of a Zen training workshop? It’s an introduction to Zen practice, but I’m also trying to get a couple of colleges to acknowledge it and give credit for it as a Buddhist studies course.

All of it seems like a very wonderful expression of what can be done with computers. But on the other hand, it seems like a very poor substitute for the real thing. The obvious question is, what’s the real thing? As I said before, a teacher really has nothing to give. The Dharma can’t be given; it can’t be received. Practice is a process of discovery. It’s got to do with realization—not knowledge or information but realization. But that doesn’t mean that knowledge and information don’t play a role in the Dharma. The course in cyberspace is an extension of what we already do. We create videos, audios, CDs. We publish a journal and books. If you package that differently and use an instrument such as the Web, you can communicate with people anywhere on the face of the earth. You make the Dharma available to anyone who has a phone line and a computer. You can bring the Dharma to those who may never be able to come to a training center. People that are housebound, isolated by distance, institutionalized. This is an experiment. I am trying to find out if it can work. Is somebody going to come to enlightenment on the Web? I doubt it, but you can never tell.

It seems highly unlikely. It also seems highly unlikely that somebody would become enlightened by hearing a pebble strike a bamboo or seeing a peach blossom. But it happened.

It seems much more likely that people are going to be hypnotized by watching the screen. That has a lot to do with the Web designer. If you make it entertaining and hypnotic, that’s what it’s going to be. If you make it challenging and introspective, that’s what it’s going to be. In the use of media—any media—we have the power to edit; we have the ability to shift perspectives. This can be done in a way that nourishes and wakes us up or it can hypnotize and poison. A key aspect of the Buddha’s teachings is to use what is at hand to nourish and empower. This project is about empowering people. If the Web can do that, it could be a very valuable adjunct in training.

You say “adjunct.” At what point is it necessary to give up the books, the audios, the computer, and step in front of a living breathing teacher? I think that will always be necessary. Practice via cyberspace is not going to replace that. There are the Three Treasures—the Buddha, the Dharma and the sangha. The personal aspect of the Three Treasures is not going to be superseded by a computer. Buddha treasure is the teacher. Dharma treasure are the teachings, the direct pointing to the enlightened mind. Sangha treasure is the community of practitioners. All those three aspects are really necessary for authentic practice to flourish. It makes a big difference when you’re sitting with a group of other people than when you’re sitting alone. Or when you have someone making demands of you face-to-face, eyeball-to-eyeball, heart-to-heart, as opposed to talking via your computer about it, where the person on the other end of the line can remain some sort of an abstraction. Take a look at liturgy. That’s where the power of the sangha comes in. There’s a big difference when you’re in a room with a group of people who are chanting their hearts out and when you’re hearing it on tape, or even watching a videotape. But I’ve used that to help my practice along when I was unable to train at a center. In my early days of practice, when I was a lay practitioner, working in the world, I created a tape that had all the sounds of the monastery on it: the wake-up bell, then the wooden han [wooden block that is struck to call people to the zendo]. The regular morning sequence leading to my dawn zazen. It was hooked to my alarm clock. The alarm clock would go off, the bell would ring, and I was transported to the monastery. Sitting periods were timed so that I couldn’t cheat. During liturgy the whole sangha chanted and I chanted with them.

So why bother going to the monastery at all? Because of the Buddha, Dharma, and the Sangha.

It’s been speculated that it won’t be too long before we’ll have computer programs so sophisticated that you won’t be able to discern whether you’re talking to a computer or a human being. What do you think distinguishes a human being from a highly advanced artificial intelligence? I saw a TV a program about robots. They had several robots programmed with artificial intelligence. These robots were to pick up little blocks of wood in a room. The one that got the most was somehow rewarded. They were programmed to learn from their mistakes. The researchers found out that after repeatedly having the robots in the room together, they began to get aggressive and knock each other out of the way to get the wood. When I saw that I thought, no difference. We don’t even know what human consciousness is. I don’t think we have even scratched the surface of its possibilities. And not being able to appreciate what human consciousness is, it’s difficult to compare it to artificial consciousness.

With all that on your plate, if you were to project yourself ahead a thousand years, what will the forms of Buddhism we are developing now look like in the future [Laughter] Moment-to-moment, nonstop flow; breath after breath.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.