The stupa, an ancient form of architecture, evolved significantly in both form and meaning with the coming of the Buddha. Cairns in ancient India were traditionally raised as monuments to kings and heroes and contained their remains. At the suggestion of the Buddha, stupas began to be built as monuments to the Awakened Ones and their disciples, a reminder of the potential for enlightenment within us all. Its corpulent shape now suggested the Buddha in meditation posture: the base, his crossed legs; the rounded dome, his shoulders; the square-shaped harmika with painted eyes, his head.

As Buddhism spread, so did the building of stupas, and each area or country developed its own style. It was only a matter of time before Western practitioners would try their hands at stupa building.

From 1983 to 1996, six Tibetan-style stupas were built in a line roughly following the Rio Grande river from Albuquerque, New Mexico, north to Crestone, Colorado. Traditionally in Buddhist countries, hundreds of monks supported by devoted lay followers contributed to stupa construction. Along the Rio Grande, each community of dharma students, or sangha, found its own way to meet the rigorous, precise, and expensive demands of building a stupa. Wise direction for the careful completion of each step, from fire pujas (prayer ceremonies) for fair weather to the construction of hundreds of thousands of tsa-tsas—tiny clay stupas—to be sealed in the bumpas, the spherical rooms below the spires, was provided by lamas—especially the Venerable Lama Karma Dorje, resident teacher at the Kagyu Shenpen Kunchab Center in Santa Fe, who has overseen the construction of three of the stupas in New Mexico.

Khang Tsag Chorten and Ngagpa Yeshe Dorje Stupa, Santa Fe

The story of stupa building in New Mexico began in the early 1970s in Santa Fe. David Padwa requested H. H. Jidral Yeshe Dorje Drudjom Rinpoche of the Nyingmapa lineage of Tibetan Buddhism to come to Santa Fe and donated the funds necessary for Khang Tsag Chorten (or “Stacked House” Stupa) to be built. Consecrated in 1973 by the Venerable Drodrup Chen Rinpoche, the eightfoot-high stupa, now under the care of the Maha Bodhi Society, is located adjacent to Upaya, a Zen center. The following year, Khang Tsag Stupa was also blessed by the Venerable Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. It is said that all stupas bless beings who see or touch them whether or not they understand the dharma. But Khang Tsag Stupa is believed to have the additional power to purify all hostility.

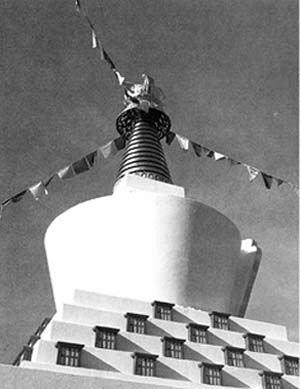

Kagyu Shenpen Kunchab Bodhi Stupa, Santa Fe

A few miles from Santa Fe’s largest mall and the infamous Cerrillos Road, one of the most hazardous thoroughfares in the state, this stupa looms up over the adjacent trailer park. Off busy Airport Road, there is a graveled driveway, and a large white-walled enclosure. As one enters, only the back of the stupa is visible-white and pristine. Circumambulating, visitors arrive at the huge, painted doors of the Kagyu Shenpen Kunchab Bodhi Stupa. Within the shrine room, a statue of the Buddha, surrounded by paintings of saints and holy beings, invites you to take refuge.

Lama Karma Dorje was sent to Santa Fe at the behest of the renowned meditation master, His Eminence Kalu Rinpoche. He began building the stupa with a local practitioner Jerry Morrelli, in 1983. They worked for three years, with help on the weekends from members of the Santa Fe sangha, and in 1986, Kalu Rinpoche consecrated the completed stupa.

Ngagpo Yeshe Dorje Stupa, Santa Fe

The newest stupa in Santa Fe commemorates the life and work of Ngagpa Yeshe Dorje, one of the first lamas to visit the area. Since 1986, Ngagpa Yeshe Dorje of the Nyingmapa lineage and master of weather ceremonies for the Dalai Lama had visited Santa Fe annually to perform the Dur ceremony (to benefit students and deceased relatives) at the Kagyu Shenpen Kunchab Bodhi Stupa. Following his death, his students, under the guidance of Tulku Sang Nga, built a stupa for him in the mountains east of Santa Fe.

There are eight traditional architectural styles of stupas, and the seventeen-foot-high Ngagpa Yeshe Dorje Stupa was built in the elegant but simple “bodhisattva” form. It was consecrated in 1995 on private land.

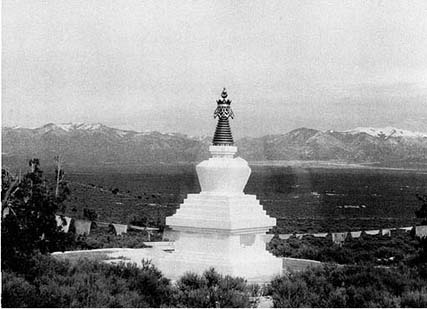

Kagyu Deki Choeling, Tres Orejas

The gift of a small statue of a stupa by Kalu Rinpoche to Norbert Ubechel, a longtime student of the Karmapa, was the inspiration for a twenty-two-foot stupa in Tres Orejas, New Mexico.

A few miles north of Taos, Tres Orejas is an almost treeless expanse between three peaks and the 600-foot drop-off of the Rio Grande Gorge. There are few inhabitants, no water, and no electricity. Despite monetary gifts for materials, the building of a stupa here was an arduous task. Lama Dorje and Ubechel hauled water for mixing cement by hand for the construction of Kagyu Deki Choeling, a “bodhisattva”-style stupa similar to the one in Santa Fe. Other students lent their labor, and on August 8, 1994, three years after the project began, the Venerable Lama Lodo consecrated the stupa. It was later blessed by the five-year-old Tsogya Gyaltso, tulku of Kalu Rinpoche, as well as by Bokar Rinpoche, a meditation master of the Kagyu lineage.

With Lama Dorje, a handful of students later built a gompa or meditation hall. From the steps of the gompa, the stupa is visible below, shining white. The cedar trees here are wind-stunted and twisted, like the treacherous road that leads to the stupa, looking out over miles of sagebrush as if from the edge of the world.

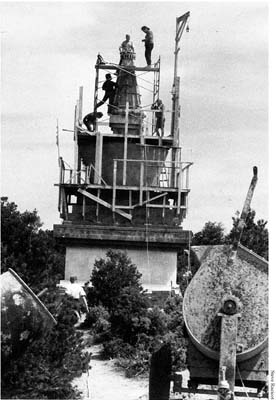

Kagyu Milo Guru Stupa, El Rito

About a quarter of a mile off NM Highway 522, which stretches from Taos toward the Colorado border, stands Kagyu Mila Guru Stupa, thirtyeight feet tall and clearly visible, an unexpected architectural jewel set close to the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in El Rito.

From 1992 to 1995, a handful of families living six miles north of the mining town of Questa gathered every Saturday morning to build the stupa. At an attitude of 8,ooo feet, work is possible only from April to November. And almost every Saturday during these months, Lama Dorje and a few Santa Fe students made the two-and-a-half-hour drive to El Rito, bringing plans for the next phase of construction, strong arms, and a generous supply of doughnuts and Gatorade.

Land, donations, and volunteer labor came primarily from students of the late meditation teacher Herman Rednick, whose teachings blended Eastern and Western meditation concepts. Lama Karma Dorje provided inspiration, guidance, and constant supervision of the project.

At the suggestion of children in the community, an inside shrine room was included in the plans for Kagyu Mila Guru Stupa. Cynthia Moku, art director at Naropa Institute in Boulder, who had helped direct painting o

f the deities in the shrine room at the stupa in Santa Fe, designed and oversaw the painting of the Kagyu Mila Guru shrine room. In the small chamber, nearly human-size representations of Chenrezig and Tara rise before the meditator with a sense of immediacy. Every detail seems to enliven the walls with a tangible spiritual presence.

In June 1995, students finished details on the stupa before the arrival of the six-year-old Tsogya Gyaltso Rinpoche and V. V. Bokar Rinpoche for the consecration. The following year, Lama Karma Chodrak, an associate and friend of Lama Dorje, arrived from India to join the community as its resident lama.

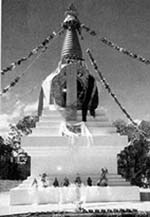

Tashi Gomang Stupa, Crestone, Colorado

Five miles south of Crestone, Colorado, high in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and surveying the San Luis valley, stands the forty-one-foot-high Tashi Gomang Stupa, “stupa of many auspicious doors,” commemorating the moment

when the Buddha first turned the wheel of the dharma.

His Holiness the Sixteenth Karmapa, who in 1980 owned 200 acres in the Crestone area, envisioned a Tibetan medical college for this area as well as a monastery with three-year retreat facilities. In 1988, Crestone dharma students received a letter from His Eminence Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche suggesting that they begin with the construction of a stupa. Due to its remote location, in an area lacking electricity and running water, and the need to build a “floating” foundation, the construction proved expensive and lengthy. Students spent five years and more than $10,000 making the hundred-thousand tsa-tsas required for the bumpa alone.

Here, too, a combination of volunteer labor and generous donations brought the stupa to completion. Kyenpo Karsar Rinpoche and Bardor Tulku Rinpoche of Woodstock, New York, directed construction, and on July 6, 1996, Bokar Rinpoche consecrated Tashi Gomang.

No-Name Stupa, Albuquerque

Rarely does a visitor to a national park have the opportunity to brush past a relic of the great Tibetan Guru Padmasambhava. But at Petroglyph National Park in Albuquerque, strollers may encounter a stupa. Consecrated by lamas and containing the many traditional objects that help make a stupa sacred, this stupa has no name. It is not advertised or even acknowledged by officials at the park’s visitor center.

The National Park Service in 1990 began acquiring the property of Harold Cohen and Arriam Emery as part of Petroglyph National Park, established to preserve the Native American rock art chipped into volcanic stones there. The move came six months after the consecration of the ten-foot-high stupa, which had taken Cohen and Emery eleven years to build on their property. According to Cohen and Emory, they lost their home and their battle to retain the stupa. Money they had saved for a future Padmasambhava Center was spent in litigation.

Lama Rinchen Thuntsok of Nepal, who had aided the couple in building the stupa and had consecrated this Nyingmapa bodhisattva-style stupa in 1989, advised them to view the process as a lesson in impermanence and suggested they build a larger stupa. The park service maintains that the stupa has been moved off what is now park land, but Cohen and Emery hope public opinion will influence park service officials to protect and preserve the stupa.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.