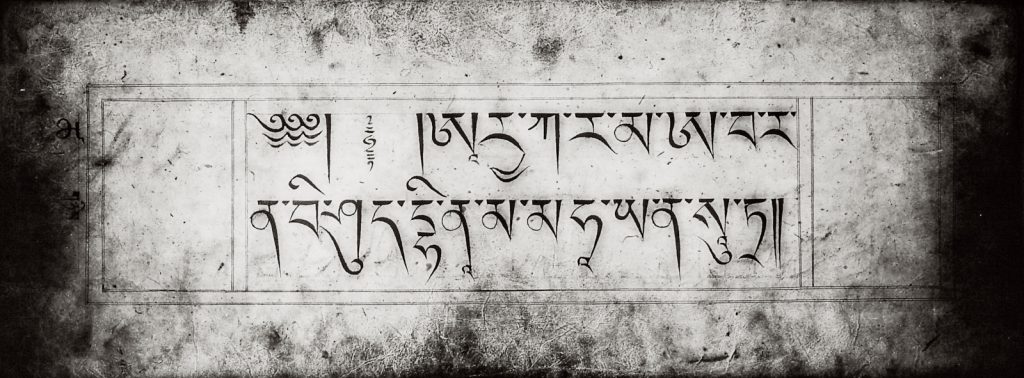

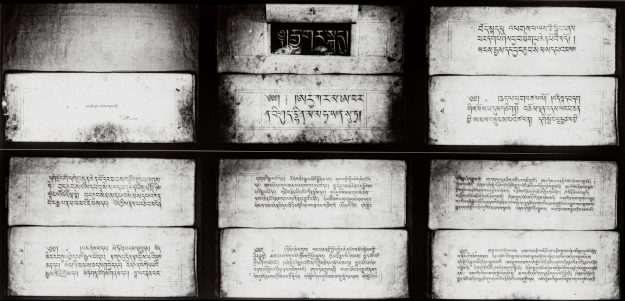

Buried amid thousands of Buddhist sutras in Tibetan and Chinese collections is a small gem, a digest of Buddhist practical teachings concentrated into four easily memorized sentences that, carefully considered, may well serve as a guide for our own contemporary dharma practice. This sutra is easy to miss—just a single page resting alongside many others that were written in short format to facilitate memorization for safekeeping in the marrow of meditation practice.

The sutra begins, like so many others, with the words “This is what I have heard,” meaning the teachings that follow were heard directly from the Buddha and then committed to memory by his close disciple Ananda. It then provides a familiar setting: a garden in Prince Jeta’s Grove, where a “community of 1,250 monks and a large gathering of bodhisattvas” have come to hear the Buddha teach the dharma. He begins by getting right to the point, saying, “There are four teachings that bodhisattvas should practice as long as they live. What are the four?”

- Bodhisattvas should cultivate an aspiration for awakening as long as they live.

- Bodhisattvas should maintain spiritual friendships as long as they live.

- Bodhisattvas should practice patience, openness, and kindness as long as they live.

- Bodhisattvas should spend some portion of time dwelling in the wilderness as long as they live.

The Buddha then repeats these four ideals in a two-stanza poem, after which the narrator concludes by telling us that “everyone in attendance rejoiced and praised the Buddha’s teaching.” That’s it. One page. No further explanation. The sutra’s author would have assumed, though, that most readers or hearers of this sutra would have encountered each of the four ideals elsewhere, perhaps many times over, articulated each time in their own cultural and historical context. Following that same pattern, here is my own elaboration on these four ideals for our Western context and the temptation to claim that the scope of these four ideals may be comprehensive enough to serve as an overall guide for contemporary dharma practice.

The Buddha’s first point—cultivating an aspiration for awakening—is truly fundamental, a necessary point of departure for an authentic spiritual practice in any tradition. Thousands of times throughout Buddhist sutras, the importance of bodhicitta—the intention, aspiration, or thought of enlightenment—is stated and emphasized. Forming this thought in our minds and dwelling on it in meditation as an image of our own deepest human purpose puts us on a path of spiritual aspiration like the one that the Buddha taught. By placing this point first, the Buddha frames it as the beginning of the path. But the sutra doesn’t just say “Start here.” It goes further, entreating us to cultivate bodhicitta “as long as we live.” It’s not difficult to understand why. Your most important aspiration, the mental image that guides and empowers your deepest sense of purpose in life, is crucial. To be guided as you go about daily life by a profound image of the point of your existence and to question, cultivate, and extend this image further and further over the course of your lifetime is to open yourself to events of awakening occurring throughout life. For this central reason, the Buddha’s first ideal is that “bodhisattvas should cultivate an aspiration for awakening as long as they live.”

The Buddha’s second ideal is also emphasized throughout the sutras. It is that “bodhisattvas should maintain spiritual friendships as long as they live.” By spiritual friendships the sutra means relationships that are attentive to what is most important in life. Spiritual friendships, broadly conceived, are those that probe beneath the surface level of human interaction in search of what our being here is all about. For most of the people gathered around the Buddha that day, and for many of us today, the Buddha was (and is) foremost among spiritual friends. But only a few people back then were (and none of us today are) personally involved with the historical Buddha. So for us that’s a “friendship” of a very different kind even if it is one that occasionally jolts us into eye-opening realizations. More direct and personal are friendships with spiritual teachers, actual people in our lives who get to know us and who can therefore be very specific in offering guidance for each of us as unique individuals. Having a personal teacher who is dedicated to the spiritual health of others and who embodies the way of living that we most admire empowers us along the Buddhist path.

Like meditation, the experience of being on your own in the wilderness inevitably means coming face-to-face with yourself in ways that just don’t occur in ordinary life.

Spiritual friendships that are mutual and collaborative are also very important. Close friends who have learned how to be honest with each other and who share the quest for insight in life can inspire and motivate each other. Practicing the dharma is a communal affair, whether the community is a large, coherent sangha or just two friends making their way through life together as mindfully as possible. The inspiration that we all need comes from beyond our limited lives, and as the Buddhist tradition evolved it recognized that anyone might potentially be that life-enhancing “spiritual friend.” Being aware of this truth and purposefully cultivating connections to others that are anchored in spiritual life opens richer and more profound dimensions of our lives. Therefore the Buddha’s second ideal for bodhisattvas is that they “maintain spiritual friendships as long as they live.”

Third, the Buddha recommends that bodhisattvas “practice patience, openness, and kindness as long as they live.” The early Buddhist virtue of kshanti, often translated as “tolerance, patience, forbearance,” appears almost everywhere in dharma discourse and here it gets singled out for exalted praise. Kshanti teaches us how to avoid self-absorption, how to open our hearts and minds to others, how to understand them, to sympathize with them, and to see things as much as possible from their points of view. When bodhisattvas train themselves to be inquisitive and open to others, they find themselves able to both tolerate others and to learn from the differences between people that might otherwise be unnerving to the point of intolerable.

But kshanti is even more expansive than this, because it includes the bodhisattva’s aspiration to maintain strength and resilience even when difficulties seem overwhelming, the difficulties of pain and suffering, of frustration and confusion, insecurity and fear, or hostility and conflict. Stories of the Buddha show us this ideal in action. When the Buddha is threatened with violence, when conflict and hostility begin to arise, he doesn’t lose his bearings. Instead, he becomes even more focused, fully intent on calming out-of-control anger and solving disputes with compassionate concern for the well-being of everyone involved. This power of personal presence is kshanti. Having cultivated it, bodhisattvas don’t fold when things get tough. They rise to the occasion with clear vision, a steady hand, and kindness. This calm, fearless openness was understood to be a sign of extraordinary strength. For good reason, then, the Buddha asks bodhisattvas to “practice patience, openness, and kindness as long as they live.”

The Buddha’s fourth ideal is that “bodhisattvas should spend some portion of time dwelling in the wilderness as long as they live.” This final point might seem out of keeping with the first three. Why is dwelling in the wilderness given equal billing with developing an aspiration for awakening, or with cultivating enlightening relationships or patience and kindness? Is substantial wilderness experience really an essential condition for Buddhist awakening? In this sutra and in many others the Buddha asserts that it is. Why? The most important reason is that in early Buddhism “wilderness dwelling” was a synonym for meditation. Buddhists who were serious about awakening carried that aspiration out by seeking some degree of seclusion from the mental spin of ordinary life so that meditative mindfulness and profound discernment might gradually become ingrained as their natural comportment. Some form of in-depth meditation practice has been considered essential to the quest for awakening throughout Buddhist history.

Practicing the dharma is a communal affair, whether the community is a large, coherent sangha or just two friends making their way through life together as mindfully as possible.

But there is something more than the practice of meditation implied here in this fourth ideal. Like meditation, the experience of being on your own in the wilderness inevitably means coming face-to-face with yourself in ways that just don’t occur in ordinary life. In social settings—even monastic social settings—consciousness is shaped by that communal setting. What and who you are is constantly being reflected back to you from others, a reflection that has a potent bearing on your sense of identity. But after even a few days alone in the wilderness that reflection begins to fade into the background and another dimension of personal accountability begins to emerge from within. You realize that there are fundamental decisions about the character of your life and death that are yours and yours alone.

Furthermore, isolation in the wilderness forces us to witness and come to terms with the enormous physical, spatial, and temporal foundations for our lives—the natural world, the planet Earth, the entire universe: it calls forth a mind-opening awareness that rarely arises in social settings. Gazing into the larger cosmos, we encounter head-on the sheer magnitude of reality and our infinitesimal position within it. Encouraging these dimensions of awareness to develop right alongside our visceral fear of being on our own helps individuate us as unique and mature spiritual beings. Expanding awareness in these ways, contemplative wilderness experience came to be considered a necessary condition for enlightened awareness.

In the Buddha’s own life, six years dwelling in the wilderness led up to his awakening and his lifelong vow to extend awakening to others. Even after devoting himself fully to teaching, however, he still realized that some time alone would be spiritually important throughout his life to rejuvenate and empower his teaching. In accordance with his example, “wilderness dwelling” in Buddhism never meant total or permanent seclusion from community. The Vinaya code of Buddhist rules forbade full withdrawal from the world, thereby declaring that although meditative solitude is important to the dharma, so is active community involvement. Similarly, Mahayana bodhisattvas rejected lifelong withdrawal from others by vowing to take collective awakening just as seriously as personal awakening. In these ways Buddhists committed themselves to cultivating bodhicitta along with and on behalf of everyone else through spiritual friendships and compassion. But with those qualifications in mind, and in conjunction with the first three ideals, the Buddha strongly advised that “bodhisattvas should spend some portion of time dwelling in the wilderness as long as they live.”

The Sutra on Four Ideals to Practice throughout Your Life, or in Peter Skilling’s translation, Four Dharmas Never to Be Abandoned, is very brief and utterly simple in its advice to practitioners. But a closer look shows us that it provides an amazingly comprehensive account of the Buddhist dharma in outline form, one perhaps worthy of memorization and practice.

An Important but Elusive Text

Although no Sanskrit original of the Sutra on Four Ideals to Practice throughout Your Life is known to exist, there almost certainly was one, since prominent Buddhists like Shantideva refer to it. Despite its apparent insignificance, its relative importance is demonstrated by the fact that we have three Tibetan translations of the sutra, two Chinese translations, and several commentaries spelling out its meaning. Nothing is known about the origins and history of this text prior to its first translation into Chinese in 680 CE. Although formatted in Tibetan and Chinese versions as a Mahayana sutra addressed to bodhisattvas, there are close parallels in early Pali sutras, and these four teachings were all initially developed there. Peter Skilling has translated it into English for us in his anthology Questioning the Buddha: A Selection of Twenty-Five Sutras (2021).

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.