The rose of a Pacific Ocean sunset poured through the windows as I woke up. I had fallen asleep on the living room couch shortly before dinner. Our house hung on a coastal hillside above a narrow beach. The tide was in below when I asked my then fourteen-year-old daughter to pour another glass of wine for me and for the first time, she refused. Her unwillingness created a split-second crack in the denial of what I had long suspected and had been watching as I sat morning zazen: I was in trouble and the trouble was alcohol.

Years later, on a pilgrimage in Poland, someone told me that once in every person’s lifetime you get to see a crack open up between the sky and the horizon. When you see the crack, you have to jump through or you will never have another chance to enter the world inside. Leap, and you are transformed. My daughter’s “no” created the opening. Time stopped and stretched out long and thin like the horizon on the ocean below. I jumped through by picking up the telephone and calling a friend who told me that she had once had a problem with alcohol. That call landed me in the community of recovery the next night. That was 1981. I’ve never looked back.

Initially I was brought up short by the seeming incompatibility between the world of Buddhism and the world of recovery. Buddhism was non-theistic, while recovery seemed to demand a belief in a Godhead that I’d walked away from in my early twenties. Buddhists talked about right speech, whereas many recovering alcoholics had foul mouths. Buddhist zendos and temples exhibited an exquisite, refined, highly developed aesthetic sense of space. Recovery rooms were often in church basements with a jumble of dirty ashtrays, coffee-stained furniture, faded linoleum floors, cold metal folding chairs, and stragglers who wandered in and out whenever it suited them.

Over time the austerities of my Zen practice gave way to breathtakingly lush forms of visualization practice and the wealth of female deities in the Tibetan tradition—in particular, the female Buddha Tara. Her vow only to be enlightened in a woman’s body was the perfect antidote for the female form that I had found so troublesome. As empty of inherent existence as male and female forms might be ultimately, Tara practice made the daily round of being in a woman’s body an extraordinary experience.

Visualization helped me focus, more so than counting the breath. It gave me an image of beauty, compassion, and kindness and helped me dissolve the negative mental habits that I could now see after removing alcohol from my life. With no anesthetic, the harsh truth of how contorted my thinking had become was increasingly obvious. The strong emphasis in Tibetan Buddhism on seeing one’s enemy as a treasure, the source of one’s spiritual growth, strongly parallels the counsel in recovery to pray for those with whom we are angry. The Vajrayana vows to not use intoxicants indicate that abstinence has long been valued as a way of furthering spiritual development, whether intoxicants were problematic or not. Taking such vows transformed my practice of sobriety into a tantric path.

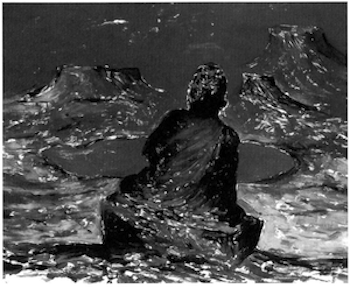

I began to see the community of recovery as a floating sangha with a different vocabulary. Meetings became sources of refuge. Enlightened speech poured out of unlikely-looking buddhas and bodhisattvas without Buddhist terminology. Wisdom emerged like a wave out of the ocean of sobriety I was swimming in, coming first out of one person’s mouth, then another’s, unpredictably, mysteriously. Thich Nhat Hanh’s insight that the next Buddha will come in the form of the small group, not an individual, began to manifest itself before my eyes.

The community of recovery is an indigenous form of Buddhism. While meditation helps change patterns of thinking, recovery points to appropriate action. For me both are necessary in the ongoing practice of sobriety.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.