Sotaesan was in the head dharma master’s room when a group curious about Won Buddhism came to pay a visit. They bowed and asked, “Where is your esteemed religion’s buddha enshrined?” The founding master said, “Our buddha has just gone out, so if you would like to see him, please wait a moment.” The group was puzzled. A little later, when it was lunchtime, a group of workers returned from the fields carrying their farm tools. The founding master pointed to them and said,“They are all the buddhas of our house.” The group was even more puzzled.

This story comes from one of the primary books of a Buddhist canon you’ve probably never heard of: that of Won Buddhism, a 100-year-old Korean Buddhist order that sprang from the individual enlightenment of a modern-day Siddhartha. This was Sotaesan [Chung-bin Park, 1891–1943], who is said to have reached enlightenment in 1916, at the age of 26 and after years of ascetic practice. It was only after his enlightenment that he read the Diamond Sutra, found that many aspects of his own insights aligned with those of the Buddha’s, and declared Shakyamuni to be his “original guide” and the “antecedent of my dharma.” Sotaesan went on to create Won Buddhism (Won means “circle”), which has variously been described as a reformed, renovated, or revitalized buddhadharma. Its purpose is to update Buddhist teachings to make them more relevant to contemporary society and more understandable to contemporary people.

It’s unclear whether Won Buddhism, whose following has been increasing worldwide, is really a new tradition of Buddhism or an entirely new religion. Won Buddhists describe their tradition in both ways, and scholars seem equally undecided about the matter. Certainly, Won Buddhism contains many elements that would be familiar to Mahayana Buddhists, but it also includes core teachings that would not be found in any other Buddhist scripture. Won Buddhism puts heavy emphasis on the integration of spiritual practice into daily life. Unlike other Buddhist traditions, Won does not place a high value on lengthy retreat time. Rather, sustained engagement with the external world is paramount: Won Buddhists are known for their interfaith work as well as for their commitment to social issues. This is not to say that Won focuses on the macro to the exclusion of the micro. Their texts include detailed directives on propriety—from shaking hands to eating to hosting guests—and on all parts of a daily routine.

There were a lot of formalities and unnecessary, superstitious rituals. He wanted to get rid of those and to make the buddha-dharma very practical and realistic.

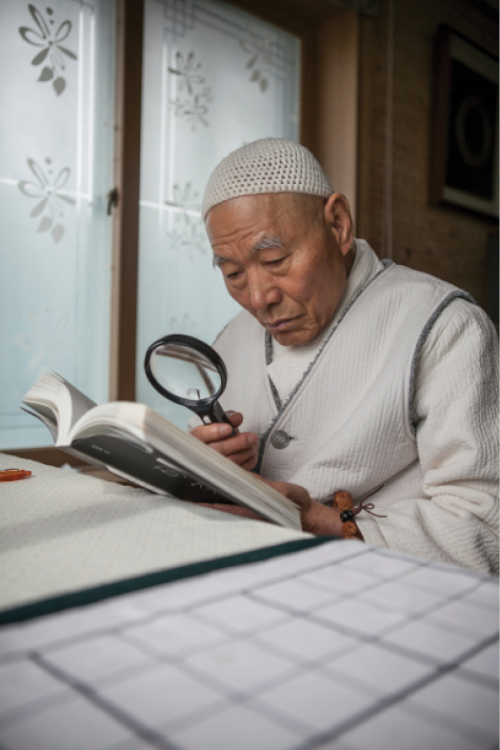

This emphasis on the average person, daily life, and pragmatism especially may help clarify the story that heads our interview. It was told to me on a sunny day last September by Reverend Dosung Yoo, the retreat director of the Won Dharma Center in Claverack, New York, when I visited on the occasion of Won’s centennial celebration. It was here, in the modern minimalist setting of the center, that I spoke with Venerable Chwasan, the fourth head dharma master of the order. There is no dharma transmission in Won Buddhism; its leaders are elected by a council composed of lay ministers and senior ministers, who are also elected. Ven. Chwasan retired in 2006 after nine years of holding the position. He is now Head Dharma Master Emeritus and lives in Iksan, South Korea. Rev. Yoo served as our translator.

–Emma Varvaloucas, Managing Editor

What sort of “reformations and renovations” did Sotaesan apply to the Buddha’s teachings? In the days when Sotaesan attained great enlightenment, Korean society was dominated by confused ideology. One of the characteristics of this confusion, for example, was the discrimination between men and women. Our founding master, very boldly for that time, abolished that discrimination. Also, especially in Korean Buddhism, different schools have their own emphasis and their own way of practice—a chanting school or a meditation school, for instance. Sotaesan wanted to gather that together to make a more balanced and complete practice. There were also a lot of formalities and unnecessary, superstitious rituals. He wanted to get rid of those and to make the buddhadharma very practical and realistic.

You mentioned “confused ideology.” Religious leaders don’t exist in a vacuum—they are always reacting to the culture of their time. Certainly Shakyamuni Buddha was reacting to the culture of his time. Could you talk a little bit about the culture that Sotaesan was reacting to? The founding motto of Won Buddhism—“As material civilization develops, cultivate spiritual civilization accordingly”—started from our founding master observing not just Korea but the whole world as technological and scientific development was advancing exponentially. Consequently, we modern people have lost our original nature, and have become completely enslaved by material things. Our mind is no longer the master of itself; instead, external things are dominating and directing our life.

Sotaesan thought this was a very sorry situation and wanted to emphasize what should be a priority and what should be secondary. He said, “Priority is our mind and the spirit. What comes next is the material civilization.”

I would like to ask about that kind of mind that is enslaved by dazzling external materials—do you also feel here in America as though you have this mind?

Yes. [Laughs.] I’m here to interview you for a Buddhist magazine, and look at me—I have my laptop, my phone, my recorder. I’m surrounded by so many electronic things that I would be upset to lose. So yes, we feel this way too. Material in and of itself is not bad. Feeble, weak mind is the problem; it’s the source of all our suffering.

The basic way to solve this problem in our contemporary society is to brighten and empower the mind. Sotaesan used the analogy of a knife. A knife is neither a wholesome nor an unwholesome thing on its own. When a knife is used by a thief, it’s a dangerous weapon. But when a knife is used by a great chef, it’s a tool that transforms ingredients into wonderful food. So everything completely depends on a person’s mind.

To intelligently utilize our material civilization is the direction of our Won Buddhist practice. It starts from working with our mind, making our mind calm and peaceful and quieting it in order to hone our innate wisdom. His Holiness really emphasized practice, not just a daily practice or going for a certain period of time to some retreat center, but to become wholly devoted to training our mind so that our life itself becomes the grace in this world.

Related: Why You’re Addicted to Your Phone

I want to go over some ways in which Won Buddhism differs from mainstream Mahayana Buddhism. One of the most prominent things is the replacement of the Buddha image with a circle, the Il Won Sang [“One Circle image”]. You won’t find, say, a statue of Shakyamuni in a Won temple. Why? The reason the Buddha image has been enshrined and worshipped all these years is to inspire people to model themselves after the Buddha’s life. But the Buddha image represents the Buddha’s body, and when the Buddha image is enshrined like this, people come to respect the form of Shakyamuni Buddha. However, the reason the Buddha is respected and venerated is not his physical body. The reason is his enlightened mind. So the circle symbolizes his enlightened mind as well as the enlightened mind of all people. When we enshrine Il Won Sang, the One Circle, it symbolizes that all people are eventually the Buddha—manifestations of

ultimate reality.

What about Won Buddhism’s understanding of why we suffer and the impetus for practice? Is it similar to mainstream Mahayana Buddhism? That is, we suffer because we’re ignorant of the true state of reality, but there is a way to get out of this suffering. How Won Buddhism views the origin of suffering and the motivation for spiritual practice—to get rid of suffering—is not that different from the traditional Buddhist understanding. For example, every morning Won Buddhists chant our version of the Heart Sutra, which is found in one of the psalms in the Won Buddhist canon.

The texts are not that drastically different. But in the specific way we apply it, there is some discrepancy. We try to make it a little more concrete, more practical.

How? We emphasize doing meritorious, beneficial work for other people. We view our practice this way: Individually, we need to progress internally. We need to enhance our spirituality to become buddhas. But externally, we need to treat other people well. We should have a very good relationship with other people in order to live in harmony with others, to live a grateful life, and to help society as a whole.

Related: The Heart Sutra: The Foundation of Understanding

You’ve used the term “grace” a couple of times today; the Fourfold Grace is integral to the Won Buddhist teachings. What do you mean by “grace,” and how do you understand its role in our lives? When our founding master said “grace,” he was referring to the indispensable relationship among all things, especially the one between ourselves and other people. You could perhaps also translate the Korean term as “gratitude.” We categorize it into four classes. The first is the grace of heaven and earth, or of the universe and nature. The second is the grace of our parents, who gave birth to us and nurtured us. Here we mean not only our biological parents but “parents” in the sense of all the people in our lives who educated us and helped us survive. The third is the grace of fellow beings, because without them, how would we do anything at all? And the fourth is the grace of law, which means the laws of the dharma as well as secular laws.

How does this work in Won Buddhist practice? We should realize and be thankful for all of these relationships and understand our dependence on other people and nature. We should pay back the great grace that we are being given by others all the time. By doing so, we will eventually restore our original mind.

How does that work? The relationship between restoring our buddhanature through spiritual practice and paying gratitude to other people can be understood in this way. Our founding master used the analogy of water. Water itself is very pure and full of life force. Wherever it goes, it nurtures the people who interact with it, and allows all beings to thrive. But let’s say that the water loses its original vitality for some reason and it becomes toxic and poisonous. Wherever the water goes, it harms the things it interacts with.

Likewise, our original mind is pure and clear; it has that same kind of vitality and inherent purity that water has. If we can keep that purity in whatever we do, wherever you go in this society you will produce a lot of beneficial results. But our mind, just like the toxic water, is tainted by our karma and our ignorance. And if we act with a poisonous mind—say, a mind filled with greed—our mind, our life itself, can bring harm to our house, to our society, and to our nation.

In this sense, spiritual practice starts from purifying our mind. We can become very naturally moral and ethical, thus making this world a better one. And conversely, by trying to be moral and ethical—by feeling gratitude for and paying back the grace of others, for instance, or by observing the precepts—we can purify our mind. So it goes both ways.

I wanted to ask specifically about the last grace, the grace of the law. When you say “law,” what do you mean? Because, as we know, not all laws are just and good. When I say “law,” I mean dharmic law: the manifestation of the dharma, truth itself. I don’t necessarily mean a law imposed by some dictator. Still, we should be grateful for secular laws as well, which are created in order to make our society orderly and safe.

I noticed on the Won Buddhist website that there are a lot of mentions of Saint Augustine, God, and other nods to Christianity. Why? It’s unusual for Westerners to see Buddhism and Christianity put together that way. Won Buddhism emphasizes the universal origin of all religions; we believe that they are all eventually the same, although everything is labeled differently as a result of arising from different cultural backgrounds. We consider other religions as our brothers and sisters and try to work together in harmony with them. They are our family. But in terms of the—how can I say it?—the hierarchy, Buddhism is the highest. [Laughs.] So maybe some are brothers and sisters and others are more like distant relatives. [Laughs.] Regardless, in Won Buddhism we try to cooperate and work with all other religions in a very active way.

So is it the Won Buddhist understanding that something like the Christian idea of union with God would be the same thing as enlightenment? Our founding master again used the analogy of water. Water is needed, not only for plants and flowers but for all kinds of animals. Without water, we cannot survive. Let’s imagine that water is the source or foundation of all reality, without which phenomena cannot exist. We label that ultimate reality “original nature” or “original mind.” In the Judeo-Christian traditions, they call ultimate reality “God” or “Creator.” Those traditions in particular describe the ultimate reality in a personified way. But when we see into the nature of reality, whether it is labeled “God” or “the Way” or “the Path,” it is essentially the same. Sotaesan used water as an analogy once again. Water can be in many forms: solid like ice, or liquid. It can evaporate. But it is always essentially water. What Won Buddhists believe about the universal origin of all religions can be understood in this way.

I want to add something else about ultimate reality that is often misunderstood by Westerners. Enlightenment is important. Its foundation is spiritual cultivation; for example, sitting meditation. But as important as spiritual cultivation is the manifestation of that practice in our daily life, which starts with observing the Buddhist precepts. We call this mindful choice in action: our deeds and words should be in line with ultimate reality. We call this the well-balanced and perfect practice. If you only understand ultimate reality but cannot use it in your daily life, your practice is not well balanced; it is not empowered.

Speaking of mindful choice in action, earlier you mentioned that Won Buddhism makes a strong statement about the equality of women. Your head dharma masters are elected. Has there ever been a female head dharma master? So far all of the heads have been male. But our second-ranked person, the executive director of the ministry, is a woman. And I expect that in the very near future we will see a female head dharma master.

A lot of other Buddhist schools in Korea, by the way—senior Zen priests and the like—were very surprised when the Won Buddhist order appointed a female minister as our executive director. We like to joke that this is one reason why Korea elected a female president for the first time [Park Geun-hye, in 2013]. [Laughs.]

You just celebrated your centennial. Of course, for a Buddhist tradition 100 years old is still quite young. What are your hopes for the future of the Won Buddhist order? As you mentioned, Won Buddhism, compared with other Buddhist traditions, has a short history. During this initial stage we would like to make the Won Buddhist order an established organization. But our real job, which in fact is the defining feature of Won Buddhism, is to work with the whole world—not just Korean society or just the Buddhist community. Everyone needs to better the world. Since you’re from the press, you know, I have some expectation from you, too, to better society. The role of reporters is huge. You should be sure to help in this area.

I think many of us got into this industry for exactly that reason. Is there anything else you’d like to add before we finish? I’d like to emphasize the qualities of Won Buddhist dharma one more time. It is not abstract. It is not mysterious. It was not created in order to provoke the average practitioner’s curiosity. The Won Buddhist teachings were created in a very rational and practical way so that they can be approached by any person. This is because our teaching was created in order to make this a far better world, so that our society can become a kind of paradise.

For more information about Won Buddhism, visit www.wonbuddhism.org.

EXCERPT FROM THE PRINCIPLE AND TRAINING OF THE MIND, BY VEN. CHWASAN:

We must guard the mind well before it can be taken away from us. And if we do retrieve it, we must guard it well afterward, for the danger of theft does not only apply to our money and physical things; forces are also watching and waiting to take our mind. These forces are what we call the five desires: appetite, lust, material desires, the desire for honors, and the desire for ease. Although I outline only five desires, the number of relatives that they have around them is truly beyond number

They are all eyeing our mind. At the center of this thieving family is greed, which commands them all. Behind it reigns the sign of the self, which governs everything. Fighting to preserve our mind against these desires is only possible with the greatest of alertness. It is said that in real life it is difficult for even ten people to prevent thievery by one person. Real-life thieves have a body, at least, and we have closed-circuit television cameras set up these days to capture them. But the thief that takes our mind has no body. There are no cameras to capture it. It steals in and snatches our mind away in a flash.

Our mind contains within it infinite principles, infinite treasures, and infinite creative transformations. If we can simply guard it, our bounty will be infinite and inexhaustible, free and easy, abounding with riches. This makes the thief all the more covetous and unyielding.

To guard against this, we need agency, we need wisdom, and we need courage. If we lack these three things, there will be no way for us to ward off the desires and guard our mind. Indeed, it is all the more difficult to reclaim it once it has been taken away. It is wiser and simpler to guard it well before this can happen, for then we need not make the extra effort to take it back.

The most comfortable and wisest people are those who watch their health when they are healthy; guard their country when it is untroubled; and cultivate their fields well when weeds are nonexistent or scarce. If we can guard our mind well in this way, without losing it or allowing it to be taken from us, then all the things contained in this place of numinous treasure become our possessions. They will never run dry no matter how much we use them, will produce limitless grace the more we use them, and will reap great blessings for ourselves and others. (pp. 130-131)

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.