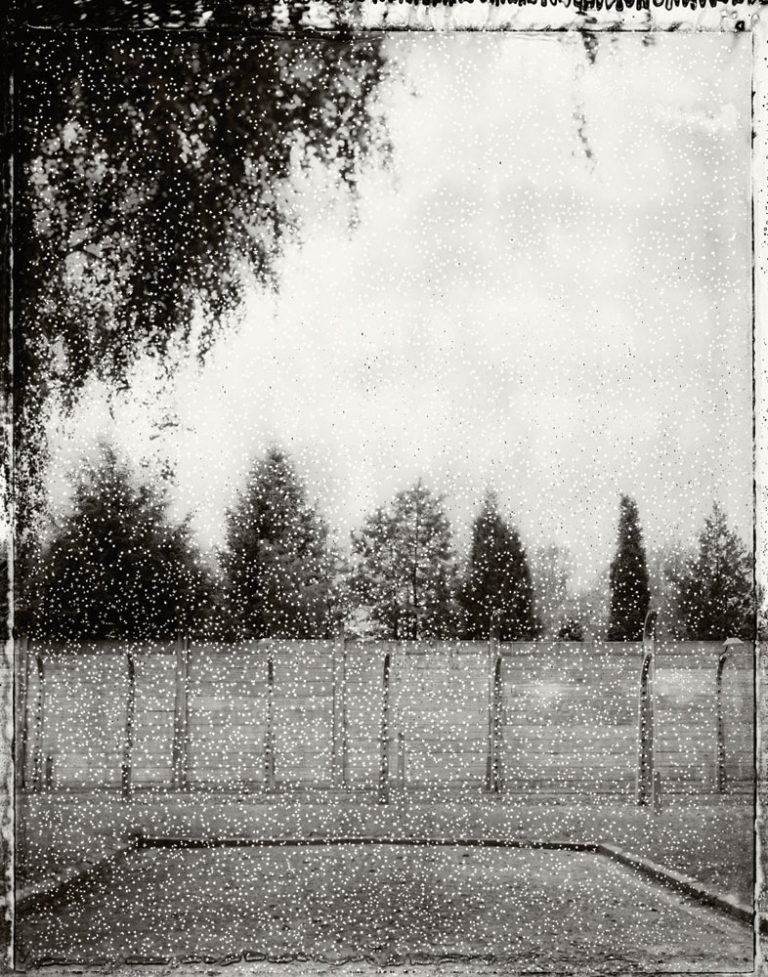

My father spent two years in concentration camps—first Auschwitz, then Buchenwald, then a smaller camp in the Black Forest. No, that does not mean I am Jewish—he was a Catholic Pole living in Warsaw, turned in to the Gestapo by an orphan boy he had assisted and arrested for his role in helping to publish an underground newspaper.

I talked with him extensively about his experiences over the years, and he once said that if I really wanted to know how he related to the whole thing I should read Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search for Meaning, which closely resembled his own perspective. I have since read it more than once, and have found its central message remarkably consonant with that of Buddhism.

One of the themes I remember my father talking about was the deep challenge of making decisions. In the camps one felt like a pawn in a vast machine—ultimately, whether one lived or died was entirely outside one’s own control. As Dr. Frankl put it:

The camp inmate was frightened of making decisions and of taking any sort of initiative whatsoever. This was the result of a strong feeling that fate was one’s master, and that one must not try to influence it in any way, but instead let it take its own course.

And yet my father’s life was saved on many occasions by his own initiative: managing to volunteer for a more sheltered job when near defeat from the exhaustion of hard labor; trading several days’ food for a typhus vaccination; bargaining his number off the list of a transport headed to an extermination camp; hiding from work in the latrine when overcome with dysentery (facing instant execution if caught); there were many such examples. As Dr. Frankl wrote, “At times, lightning decisions had to be made, decisions which spelled life or death.” The most important decision faced by all the prisoners, however, was one even more basic and existential than any of these:

Every day, every hour, offered the opportunity to make a decision, a decision which determined whether you would or would not submit to those powers which threatened to rob you of your very self, your inner freedom. . . .

. . . in the final analysis it becomes clear that the sort of person the prisoner became was the result of an inner decision, and not the result of camp influences alone.

The prisoners had no control over their external circumstances, which were unrelentingly and unimaginably bleak. The one and only freedom they could retain was the freedom to choose how they responded inwardly to these circumstances. Dr. Frankl referred to this as spiritual freedom: “Everything can be taken from a person except one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

In Buddhist psychology too, there is the insight that every single moment of consciousness requires us to make a volitional decision (cetana) that manifests as action (karma). These both shape and are shaped by the underlying dispositions (sankharas) of our character, which are profoundly malleable. It is common to think of karma as a sort of fate to which we are subjected, but it is more central to the Buddha’s message that karma is the opportunity we have each moment to choose what sort of person we are to become next.

We have no control in the moment over what comes to us in the way of “old karma,” since this has been forged by previous decisions and actions, made by both ourselves and others. But in each moment we have the obligation—and the privilege—of forging “new karma” by deciding and acting upon what is arising in either wholesome or unwholesome ways. The Sallekha Sutta (MN 8) puts the matter this way:

This is how one is to practice austerity:

Others will be cruel; we shall not be cruel here.

Just as there may be an uneven path

and another even path by which to avoid it,

so too, a person given to cruelty has non-cruelty by which to avoid it.

In other words, we all have within us very primitive reflexes for self-survival at any cost (the unwholesome roots of greed, hatred, and delusion), but we also have more evolved impulses toward self-less action (the wholesome roots of generosity, kindness, and wisdom). And we are called upon to make a choice, each and every moment, along which of these two paths we will place our step.

Both Viktor Frankl and my father were somehow able, under the most challenging circumstances, to make the decision to preserve their freedom and dignity, and by doing so were able to go on to live long and meaningful lives. The Buddha also encourages us to choose our own way, a way that is wholesome and noble. We are fortunate to have more comfortable circumstances in which to do so.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.