I first met Thich Nhat Hanh in May 1966.

At the time Lyndon Johnson was America’s president. The steadily rising level of US troops in Vietnam reached 384,300 that year and within the next eighteen months would expand to half a million. But support for the war was shrinking. The nation had become deeply divided—never before had so many Americans opposed a war being fought by their own government. There were huge protest demonstrations in many cities. Conscientious objection was on the rise; thousands were refusing to serve in the military. Young men were burning their draft cards or crossing the border to Canada.

A significant part of the war’s opposition was religious. In America the ranks of protesters included many prominent Christians and Jews, while in Vietnam tens of thousands of Buddhists, many of them monks whose monasteries had been scarred by war, were engaged in antiwar activities. Their demonstrations had been brutally attacked by South Vietnamese police, and even display of the Buddhist flag was banned. In 1963, one leading Buddhist monk, Thich Quang Duc, had stunned the world when he burned himself alive in response to anti-Buddhist repression by the US-backed Saigon government.

In July 1965, Al Hassler, executive secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR)—the oldest and largest peace organization in the US—had led a fact-finding mission to Vietnam that included meetings in Saigon with Buddhist leaders. The monk who most impressed Hassler was the Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, and a friendship quickly took root between them that was to influence the rest of both men’s lives.

Hassler had realized that Thich Nhat Hanh had the potential to help pro-war Americans, including legislators, rethink their Cold War perceptions about what was happening in Vietnam. He wanted Nhat Hanh’s voice to be heard in America, and he set about arranging for Nhat Hanh to come to the States the following year.

I met Thich Nhat Hanh at the Fellowship of Reconciliation headquarters in Nyack, New York. This was in the spring of 1966; he was 39, and I was 24. I had just been appointed director of the Fellowship’s Vietnam program while also serving as co-secretary of the Catholic Peace Fellowship. In introducing him to the FOR staff, Al Hassler explained that Nhat Hanh was a leading figure in the development of “engaged Buddhism,” a movement of religious renewal that linked insights gained from Buddhist teaching to hands-on engagement in situations of suffering. He had also played a leading role in efforts to bring the several strands of Vietnamese Buddhism into greater harmony, resulting in the creation of the Unified Buddhist Church. In addition to these and other accomplishments, he was a widely read author in his homeland, though at the time none of his many volumes of poetry and other writings had yet been published in English or other Western languages.

Addressing the Fellowship staff, Nhat Hanh described the impact of the war on ordinary Vietnamese people, the obliteration of entire villages, and the actions of the Buddhist-led peace movement that allied itself with neither of the warring sides. His stress was not on politics but on war-caused suffering. “The fact that the war kills far more innocent peasants than it does Vietcong is a tragic reality of life in the Vietnamese countryside,” Nhat Hanh said. “Those who escape death by bombings are forced to abandon their destroyed villages and seek shelter in refugee camps where life is even more miserable than it was in the villages. In general these people do not blame the Vietcong for their plight. It is the men in the planes who drop death and destruction from the skies who appear to them to be their enemies. How can they see it otherwise?”

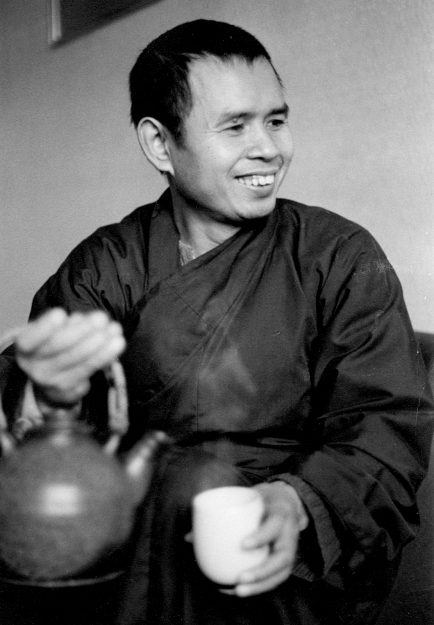

I was impressed not only by what Nhat Hanh had to say about his homeland but by his entire manner. He was as modest as the dark brown monastic robe he was wearing. When questions were raised, he looked at whomever he was addressing with alert, unhurried, attentive eyes. He spoke slowly, carefully, sparingly in Vietnamese-flavored English. His quiet voice reminded me of wind bells. There were restful silences between words and phrases. Afterward I said to Al Hassler, “I could listen to this guy for hours even if he were reading aloud from a telephone book.” Al laughed. “Me too!”

It did not cross my mind that day that Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings would one day circle the world or that his books would sell in the millions of copies. At the time, I saw him not as a religious teacher but as a peace advocate. But I left the meeting deeply impressed, aware that this young, soft-spoken monk from Vietnam was the sort of person who changes lives.

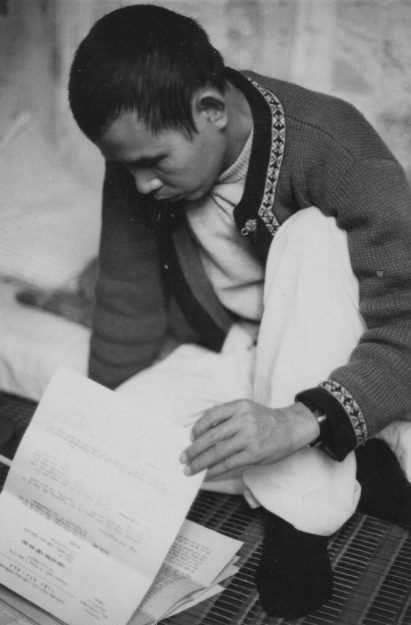

Thich Nhat Hanh’s first public appearance was on the first of June 1966 at a press conference in Washington, where he presented a Vietnamese Buddhist proposal for ending the war. He prefaced the plan with the reassurance that he was not anti-American. “It is precisely because I have a great respect and admiration for America that I have undertaken this long voyage to your country, a voyage that entails great personal risk for me upon my return to South Vietnam. Yet I assume this risk willingly because I have faith that if the American public can begin to understand something of what the Vietnamese people feel about what is happening in our country, much of the unnecessary tragedy and misery being endured by both our peoples might be eliminated.” The war in Vietnam, he said, “pits brother against brother, the Vietcong against the supporters of the Saigon government. Both sides claim to represent the Vietnamese people, but in reality, neither side does.” The proposal, which he characterized as offering a “third way” between the warring sides, called on the US to support the Vietnamese people in developing a government truly responsive to their aspirations. Among the principal obstacles to peace, Nhat Hanh said, was America’s support for “those elements which appear to be most devoted to US wishes for Vietnam’s future” rather than the wishes of the Vietnamese people themselves.

Following up on the press conference, the FOR staff arranged a series of meetings for Nhat Hanh with influential figures—key religious leaders, senators and congressmen, editors of major newspapers, and even Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. A cross-country lecture trip followed. By 1967, Nhat Hanh was becoming widely known as an independent Vietnamese voice representing not only Buddhists but all those who were victims of the war in Southeast Asia.

I left the meeting impressed, aware that this young, soft-spoken monk from Vietnam was the sort of person who changes lives.

Wherever he went, Nhat Hanh impressed and disarmed those he met. His gentleness, intelligence, and sanity, plus his fluency in English, made it impossible for most who encountered him to hang on to their stereotypes of what the Vietnamese were like. Not only did his peace proposals make sense, but the vast treasury of Vietnamese culture and Buddhism spilled over through his stories, poetry, and explanations. In the course of his lecture trips, he was able to help thousands of Americans glimpse the war through the eyes of Vietnamese peasants, neither Communist nor anti-Communist, who were laboring in rice paddies and raising their families in villages surrounded by ancient groves of bamboo. After an hour with Nhat Hanh, many who met him were filled with anguish at America’s military intervention in the tribulations of the Vietnamese people. No ideology could justify the horror of the skies raked with bombers, houses and humans burned to ash, and children left to face life without the presence and love of their parents and grandparents.

Predictably, Nhat Hanh’s peace activities were not appreciated by the US-backed government of South Vietnam. He was denounced as a traitor by several generals, while the Hanoi regime accused him of being pro-American. Warned by friends in Vietnam that he would be in grave danger should he return home, he found himself in exile. What was to have been a three-month absence made him an expatriate for more than forty years.

One of the persons Nhat Hanh had long hoped to meet while in the United States was Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk whose widely read books had done so much to revitalize contemplative spirituality. Merton was by then also known for his opposition to the war and also for his deep respect for Buddhism. In late May 1966, Merton welcomed Nhat Hanh, plus John Heidbrink of the Fellowship of Reconciliation staff, to the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky for a two-day visit.

The two monks stayed up late into the night in Merton’s hermitage, sharing the chants of their respective traditions, discussing methods of prayer and meditation, comparing Christian and Buddhist aspects of monastic formation, and talking about the war.

Afterward, Merton said to his fellow Trappists, “Thich Nhat Hanh is a perfectly formed monk,” and that he regarded his guest’s arrival as an answer to a prayer. “In meeting Thich Nhat Hanh,” Merton said, “I felt I had met Vietnam.” Merton also wrote of their visit, calling Nhat Hanh his brother: “He is more my brother than many who are nearer to me in race and nationality, because he and I see things exactly the same way.”

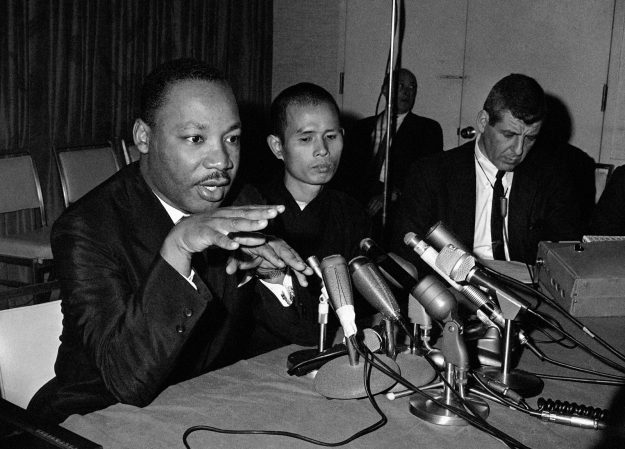

Another person who immediately bonded with Nhat Hanh was Martin Luther King Jr. Al Hassler arranged for the two to meet in Chicago during Nhat Hanh’s lecture tour. “Dr. King is not only a brave man but a gifted listener,” Nhat Hanh later told the Fellowship of Reconciliation staff. “As with Thomas Merton, you can say just a little and he understands a great deal. I told Dr. King that many people in Vietnam regard him as a bodhisattva. It was a new word for him. I explained that it means someone who is fully awake, like the Buddha.”

In January 1967, Dr. King nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize, writing that “I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize than this gentle monk from Vietnam,” and that the honor would “remind all nations that people of good will stand ready to lead warring elements out of an abyss of hatred and destruction. It would reawaken people to the teaching of beauty and love found in peace.” In April of that year, Dr. King delivered his famous Riverside Church speech, in which he first declared his opposition to US intervention in Vietnam.

Wherever he went, Nhat Hanh impressed and disarmed those he met.

Al Hassler was the staff person who most often accompanied Nhat Hanh wherever he went in America, but occasionally another Fellowship of Reconciliation staff member might have that privilege. One evening I was pressed into the job.

The event Nhat Hanh and I attended—a small gathering at a posh apartment on Park Avenue in midtown Manhattan—turned out to be disappointing. Slipping away at the earliest possible moment, we returned to the street. I suggested perhaps a cup of tea wouldn’t be a bad idea. Nhat Hanh agreed. We found a fluorescent-lit Chinese café and settled into a candid and intimate conversation. I felt a deep sense of connection, an almost audible click. Nhat Hanh might have felt something similar, because he asked if in the future I would accompany him on his FOR-arranged travels whenever Al Hassler was unavailable. After that evening we traveled together a great deal, from the East Coast to West and back. During our travels, I began to refer to Thich Nhat Hanh as Thay (pronounced tie), the Vietnamese word for “teacher.” He was certainly a teacher for me.

In conversation Nhat Hanh would speak sometimes of the importance of what he called “mindful breathing,” a phrase that seemed quite odd to me at first. Yet I was aware that his walking was somehow different than mine and could imagine this might have something to do with his way of breathing and also his way of listening. Even if we were late for an appointment, he always walked in an attentive, unhurried way. “Better to be late,” Nhat Hanh said, “than breathless. What is most important is to be in the present moment.” It was from Nhat Hanh that I first became aware that walking with attention to breathing provided opportunities to repair the damaged connection between the physical and spiritual.

One evening at a large Protestant church in St. Louis where Thay was speaking, a man stood up during the question period and spoke with searing sarcasm of the “supposed compassion of this Mister Hanh.” He asked, “If you care so much about your people, Mister Hanh, why are you here? If you care so much for the people who are wounded, why don’t you spend your time with them?”

When the man finished, I looked toward Thay in bewilderment. What could he, or anyone, say? The spirit of war had suddenly filled the church. It was hard to breathe.

There was a prolonged silence. Then Thay began to speak—quietly, calmly, with a sense of personal caring for the man who had just bombarded him. Thay’s words seemed like rain falling on fire. “If you want a tree to grow,” he said, “it does not help to water the leaves. You have to water the roots. Many of the roots of the war in my country are here, in your country. To help the people who are being bombed, to try to protect them from this suffering, it is necessary to come here.”

The atmosphere in the room was transformed. In the man’s fury we had experienced our own fury. We had seen the world as through a bomb bay. In Thay’s response we had experienced an alternate option: the possibility—brought to Christians by a Buddhist and to Americans by an “enemy”—of overcoming hatred with love, of breaking the seemingly endless counterreactive chain of violence.

But after his response, Thay whispered something to the chairman and walked abruptly from the room. Sensing something was wrong, I followed Thay outside. It was a cool, clear night. Thay stood on the sidewalk at the edge of the church parking lot. He was struggling for air like someone who had been underwater and who had barely managed to swim to the surface before drowning. I had never seen him like this. It was several minutes before I dared ask him how he was or what had happened.

Thay explained that the man’s comments had been terribly upsetting, and he had been tempted to respond to the man with anger. Instead he had made himself breathe deeply and very slowly in order to find a way to respond with calm and understanding. But the breathing had been too slow and too deep.

“But why not be angry with him?” I asked. “Even pacifists have a right to be angry.”

“If it were just myself, yes,” said Thay. “But I am here to represent the Vietnamese peasants. I have to show those who came here tonight what we can be at our best.”

As I gradually came to know Thich Nhat Hanh, I began to realize that I and many other peace activists tended to be prisoners on a conveyor belt of activity that often led to burnout, not only due to physical exhaustion but also because of compassion exhaustion. Being attentive to suffering on a daily basis is hard work. Many of us were overwhelmed by a sense of failure and futility. Nor was there much peace in the peace movement. It dawned on me that Thich Nhat Hanh could help me, and others like me, acquire a more sustaining form of social activism. So many of us were overlooking something as essential to our lives and work as breath itself.

It was, for me those many years ago, astonishing news that something as simple as attention to breathing—as breath itself!—could play a significant part in meditation and prayer. Over time, I began to be aware that one of the obstacles to entering a meditative state is that the opportunities are too close at hand, too ordinary, too prosaic: in the kitchen, in subways and buses, in supermarket waiting lines, on sidewalks, on staircases, on picket lines . . . literally everywhere. I came to think of mindful breathing as being a kind of secret, like a mystery novelist’s idea of hiding diamonds in a goldfish bowl put in plain view, hard to see precisely because they are right out in the open.

During our travels, Thay was often asked questions about Buddhism, and I was frequently surprised by his responses. One thing he was asked time and time again was some form of the question, “What is Zen?” On one occasion, Thay tapped the microphone in front of him. “Zen,” he said, “is perhaps this microphone, and if it is not this microphone I do not know what it is. To know what Zen is you must know what Zen is not, and I cannot answer that question. I do not know if it is possible to point out what is religious and what is not. I do not know if the microphone is religious or not religious.”

“The Buddha is truth, and the only thing that keeps you from finding truth is your conviction that you have already found it.”

Another time, a student of Buddhism whom we met in Santa Barbara, California, asked what it meant to seek the Buddha and what happens when you find him. Thay answered, “I am a Zen master—and, as you know, Zen masters always reply incomprehensibly. So I will say that you only find the Buddha by killing the Buddha whenever you find him.” Then he laughed and said, “But I am a nice Zen master, so I will tell you that the Buddha is truth, and the only thing that keeps you from finding truth is your conviction that you have already found it. So whenever you find truth, you must recognize it is a lie, kill it, and go on in the search for truth. Becoming a bodhisattva—someone fully awake—is not reached via methods or ideologies or study or fasting. Memorizing all the sutras is helpful but will not force open the door. You can sit a thousand hours on a meditation cushion and still be stranded. A diet restricted to green leaves will not assure your entrance into the Pure Land. If you think you have encountered the Buddha, it is more likely that it is only a concept of the Buddha—an idol, an illusion. To encounter the true Buddha, we have to kill that illusion.”

It isn’t easy to describe the influence Thay had on me in the course of our travels. Partly his influence came simply as guidance about what I would call being in a state of prayer, and Thay would call mindfulness or being in the present moment. In contrast with the Catholic priests and prominent peace activists Dan and Phil Berrigan, good friends with whom I was also working closely, Thay exerted no pressure on me to do more than I was already doing to end the war in Vietnam. But because of Thay, Vietnam was no longer a distant country. It was as close as Thay’s voice. Its tragedies were mine. I had broken into what Thomas Merton called “the human dimension.”

When I was invited to be part of a community that was preparing to impede military conscription by burning draft records, with the probability of a long period in prison as a consequence, part of the reason I said yes was my love of Thich Nhat Hanh and the awareness that Vietnam—though I had never been there except through Thay—was part of my home.

In September 1968, I was one of a group of fourteen who burned thousands of draft files on a small square in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. During the trial the following spring, we attempted, with some success, to put the war on trial, but in the end we were found guilty, as we expected. While serving a year in prison—1969–70—I received a letter from Thay.

“Do you remember,” he asked, “the tangerine we shared when we were together? Your being there is like the tangerine. Eat it and be one with it. Tomorrow it will be no more.”

♦

Adapted from Eyes of Compassion: Learning from Thich Nhat Hanh by Jim Forest, published by Orbis Books.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.