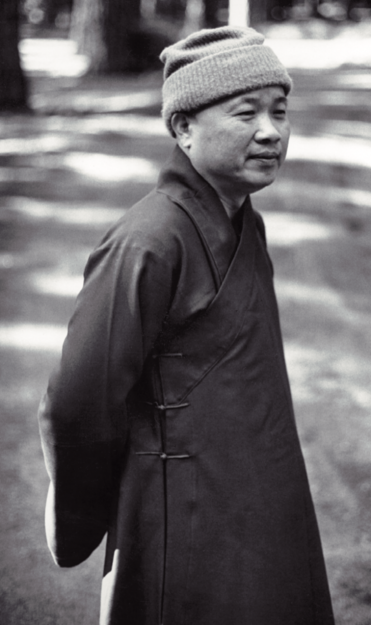

When my teacher, Most Venerable Dr. Thich Man Giac, would say “In my mind,” he would always point to his heart. Initially, I thought it was cute; it took me a while to understand just how integral his heart and his mind were for him. It was not “cute”; it was just natural, accurate. Everything he did was based on his compassionate heart (or should I say mind?).

At the traditional service held forty-nine days after his passing, I spoke with a close associate of his who had known him for decades here in America and in Vietnam. He was brought to tears as he expressed how unusual Man Giac was as a spiritual leader and as a monk. As the Supreme Patriarch of the Vietnamese United Buddhist Churches of America–an organization with millions of followers, with temples stretching across the United States–he honored the Buddhist traditions and maintained the cultural customs of Vietnam. He also fully understood that each country had adapted Buddhism to its culture; he wanted Buddhism to not be a “foreign” religion, but to “become American,” to adapt to the American ideals of equality, freedom, and nondiscrimination, and to be brought into the twenty-first century. He campaigned for human rights causes tirelessly, visiting refugee camps and holding hunger strikes, yet he was never political; the aim of his work was simply to end suffering. He didn’t talk idly about the Four Noble Truths or about the bodhisattva vows, he just embodied them.

It’s no surprise, then, that the greatest lessons I learned from him were not in any formal class, but simply by being with him and observing. During my ordination process, we discussed the shaving of the head, a common Buddhist practice. In his heavily accented English, he blurted out that “basketball players are not monks.” Now that could be a koan in itself. As he explained, priests from different Buddhist traditions in different countries are vegetarian or are not, are married or are not, eat before noon or all day, have hair or do not. If you look at the statues and paintings of the bodhisattvas, they have hair; so do the statues of the Buddha (unless you adhere to the story of the 108 snail martyrs who gave their lives to protect the Buddha from sunstroke).

According to Man Giac, a bald skull did not mark any being as a true follower of the Middle Way. “Having a shaved head does not make you a Buddhist priest, a monk, or a nun; if you wish, what matters is if you have hair in your mind, if you are pure and free from delusion in your mind.” Pointing to his heart, he said, “No hair in your mind.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.