B. Alan Wallace trained for ten years in Buddhist monasteries in India and Switzerland. He has taught Buddhist theory and practice in Europe and America since 1976 and served as interpreter for numerous Tibetan teachers, including His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Author of the forthcoming Buddhism with an Attitude (Snow Lion Publications), Wallace has contributed to more than thirty books on Tibetan Buddhism, medicine, language, and culture. He presenty teaches in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara. This interview, conducted by Brian Hodel, is an expanded version of an interview that first appeared in Snow Lion, the newsletter of Snow Lion Publications.

An excerpt of his new book appear here.

Have Tibetan teachers of Buddhism had to make changes to accommodate a growing community of Western students?

In Asia—India, Nepal, Sikkim, and Bhutan, for example—since the late 1960s or early ’70s, lamas have given public teachings that have been primarily directed to the Tibetan community, but Westerners have always been welcome to attend. Unless the teachings were of a very high level of, let’s say, tantric teachings. Even then, if Westerners qualified, had the appropriate initiations, or were encouraged to attend by their own lamas, then they were welcome to attend those as well. There are a number of Tibetan monasteries in the south of India where training is quite open to Westerners.

And in the West?

In the West, when Tibetan lamas offer teachings the format is altered because these lamas are usually on tour. It’s common for them to give weekend workshops or one-night lectures. Or they may stay in a place for a longer time and give a one-week or a two-week retreat. But, for the most part, that’s as long as it ever gets. Then some are resident lamas with their own centers where more sustained training is given.

In the monastic setting, teachings follow a coherent order. What’s the effect of teaching outside this format?

In the West, it is very common that a lama will pass through a city and give a tantric Buddhist initiation and a weekend of esoteric teachings on visualization practices or ways of experiencing a state of pure awareness. What’s missing here in the vast majority of cases is the profound context: the theoretical context, the context of faith, the context of a mature spiritual community. The teachings themselves, though perfectly traditional, are being introduced in a radically nontraditional context. And this, I think, has on numerous occasions led to terrible misunderstandings and a great deal of unnecessary conflict, unrest, confusion, and suffering.

Such as?

Back in the late 1970s some very fine lamas came to this country and gave a number of advanced teachings. A lot of the Westerners in attendance, young men and young women, got very enthused by these lamas who were teaching in concert, and a number of them, right off the bat, were ordained right then and there with no context whatsoever, with no monastery, no abbot, and no proctor to teach them the vows and help them to assimilate and apply the vows in daily life. I think the vast majority, if not every single one of that group, eventually returned their vows, because there was no context for them and they entered into it with little understanding of the step that they were taking.

If a bunch of new people wanted to take ordination right off the bat in Asia, would the lamas have done it? It sounds kind of off-track in either context.

In Asia, responsible elder monks first question those who express a wish to take ordination, and they grant that desire only if they feel that the would-be monks or nuns are sufficiently prepared and if there is some place where the novices can receive appropriate monastic training. Here in the West we live in a profoundly non-monastic and non-contemplative society. And so to adopt these profound and esoteric contemplative practices and the monastic way of life without sufficient context is highly problematic. And I am not sure that this has been sufficiently addressed by many lamas who are basically living in Asia and occasionally touring the West for weeks at a time. They seem to feel that since what they are giving is traditional, what is being received is being received in a traditional fashion. But in many cases that just isn’t so.

Are you saying this group of lamas that gave the ordination vows was unaware that these people had no context at all?

It was pretty obvious. So what was their rationale for giving ordination and advanced teachings in meditation? I have heard some lamas say, “I’m sowing seeds, and it’s better for people to be exposed to Buddhism imperfectly than not be exposed at all.” And, to take a New Testament parable, some of the grain will land on rocks or be eaten by birds and some grains will actually fall into the soil and be fertilized and they will sprout. That may be a very small proportion of the people attending the teachings, but for some the teachings will sow the seeds for a sustained and nourishing spiritual practice that will come to great maturity and benefit themselves and others. And as for the others, the lamas’ rationale, as I’ve heard at least some of them express it, is that at least these people have been exposed to the dharma.

Are there other more recent examples of this problem?

My own feeling is that Buddhist tantric initiations, practices, and vows are often given out too indiscriminately. All these practices entail taking on serious commitments, and if people with little or no background in Buddhism take such vows and so on without sufficient background, this can lead to disillusionment and confusion.

Why not just stick to basic, foundational teachings? Why are these high teachings even given as introductions?

I think the simple answer is: if lamas confined themselves to teaching topics such as ethical discipline, renunciation, and the cultivation of lovingkindness and compassion, few people would come. Before going on tour, lamas often ask what kind of teachings Westerners would like, and the response is often a request for advanced teachings, say on Dzogchen or Mahamudra, which are concerned with exploring the nature of pure, conceptually unstructured awareness, or one’s own inner Buddha-nature. Out of compassion and the wish to fulfill others’ wishes, many lamas comply. Perhaps their rationale is that people will probably get more benefit hearing something they are really interested in, than in hearing valuable teachings in which they have no interest—in which case they probably wouldn’t show up at all anyway.

So we have a commercial situation of supply and demand, very unlike the dharma scene in Asia. In the West teachings are advertised and profit is made. So whether we like it or not, there’s a commercial aspect to the teachings in the vast majority of cases. And even if lamas have wealthy benefactors who are taking care of them, someone still has to pay for their travel expenses and the use of the teaching site. That’s the long and the short of it.

Isn’t there a problem here of appealing to the ego? I may request the highest teachings because I want to attain realization as quickly as possible. But of what value are the higher teachings if I haven’t absorbed the basics? Isn’t that like throwing seed on stones?

In my experience, lamas who are willing to give these very advanced teachings will strongly emphasize the importance of the foundational teachings and practices, such as those concerning the cultivation of renunciation and compassion. One of my teachers, Gyatrul Rinpoche, has often given advanced teachings on Mahamudra and Dzogchen, but he hammers home the message time and time again: “Yes, these are profound teachings. Yes, it can be very helpful for you to do the practice. At the same time, do not overlook the foundational teachings, because these are the ones that, in the foreseeable future, are much more likely to really bring about evident transformation for the better in your own minds and in your own lives.” Gyatrul Rinpoche has taught for more than two decades in this country. He still emphasizes the foundational teachings, but at times students complain that they have already heard these teachings and don’t want to hear them anymore. In many cases, even though these students have not realized the foundational teachings through practice, they’ve heard them and more or less understood them intellectually. But out of familiarity they have lost interest in these teachings, no longer wishing to practice them, and yearn instead for something new, something profound, something that promises to bring about the kind of spiritual transformation they haven’t gained so far.

As Gyatrul Rinpoche has often commented, it’s not that the lamas don’t want us to hear or practice these higher teachings. They just don’t want us to do them instead of the foundational teachings, because then we’ll wind up following the more advanced practices without benefiting from them, while shunning the more basic practices and therefore getting no practical benefit at all. The advice I’ve heard and embrace is that we need to keep our feet planted in the ground of the foundational teachings and reach to the sky with the more advanced teachings.

If many Western students are getting the higher teachings toward the beginning but then have to go back to the foundational teachings, isn’t this counterproductive?

It certainly can be!

That doesn’t sound very efficient.

Overall, I don’t think there is much efficiency in the way that teachings are taught or practiced in the West, even though we, being a consumer society, a business-oriented society, prioritize efficiency. Also in the West, various lamas of all the different orders of Tibetan Buddhism are passing through town for weekend events. And this means you have the possibility of being exposed to a hodgepodge of weekend teachings and initiations and your exposure to Buddhism becomes random. It’s like going to a buffet. You pick up whatever is coming through, but there’s no order to it, no continuity, no progressive development, and so again: it’s very inefficient. This can turn a lot of people into dilettantes, as they acquire a “taste of the town” of Buddhism, dabbling in one flavor after another, without gaining proficiency in anything.

This lack of continuity is due, in part, to a lack of patience. As a consumer society we want snappy results. That’s part of what we consider to be efficient. If we go to a teaching we want to see results in a weekend, or at least in a week! And some teachers are willing to cater to that type of mentality. I’ve even seen advertisements for Tibetan Buddhist events that sound like Madison Avenue hype.

The upshot is that a number of lamas generally regard Westerners—with many fine exceptions—as being impatient, superficial, and fickle. And in Tibetan society, fickleness is considered to be one of the worst of vices, while reliability, integrity, trustworthiness, and perseverance are held in high regard. So a few of the finest lamas are now refusing even to come to the West, because they figure they could be spending their time either teaching Tibetans in Asia, or they could simply go into retreat and meditate. Some are feeling—given the brevity and preciousness of human life—that devoting time to people with such fickleness and so little faith is time not very well spent.

Along with the inefficiency of these “buffet-style” teachings, isn’t there also a danger of picking and choosing, and trying to synthesize your own unique stairway to heaven?

That’s a danger, yes. But I believe a balance needs to be struck. One extreme is what you have just suggested here, individualism: “I know what’s best for me! I will choose what I like.” This is like a kid going into a restaurant and saying, “I’ll just take what tastes good.” The underlying problem here is that, after all, we’re coming to dharma because we’re not enlightened, not because we’re already enlightened. If we’re not enlightened, this means we’re deluded. That’s the core issue in Buddhism. And so a person who is ignorant and deluded says, “I’m going to set myself above the tradition with its own worked-out strategy and sequence of practices that have been offered down over generations by enlightened beings.”

The other extreme is a dogmatism that is radically disengaged from people’s actual experiences through the practice of dharma. Tibetans over generations have worked out strategies, teachings, rituals, and sequences of practice that were designed for Tibetans. They did not simply replicate Indian Buddhism.

I have a lot of confidence that they did retain the core, the essence of Indian Buddhism. But theirs is also a tradition that modified itself over the centuries to best suit the Tibetan mentality, the Tibetan environment, Tibetan customs. Now, the proof is in the pudding, because what turned out was generation after generation of great Tibetan adepts. Going back to the time of Padmasambhava, Sakya Pandita, Milarepa, Tsong-kha-pa, right on into the twentieth century—it’s worked!

With that success, it is possible to conclude that since it worked for the Tibetans, we Westerners must take their tradition, the pure teachings, exactly as they were taught in Tibet, and introduce them in Los Angeles or New York City. But the reason those teachings are considered to be pure is that they worked in Tibet. The test is, do they still work? If those same teachings, in the same format, with no adaptations for the West, are transplanted in Europe or America, ignoring the difference of cultural context, this can wind up being rigid, fundamentalist, and dogmatic, without even noticing whether those teachings are producing the same type of wonderful effects and transformations in Western practitioners that they did in Tibetan practitioners.

If they do not yield the same benefits—if after thirty or forty years of Tibetan Buddhism in the West we do not have people here ascending along the path to enlightenment, developing deep states of meditative concentration, contemplative insight, profound compassion, and unveiling the many wondrous natural resources of consciousness itself, then we have to ask the question: Are those same teachings that have worked for the Tibetans equally effective for Westerners?

Do we now have Western adepts comparable to the twenty-five principal disciples of Padmasambhava, who achieved extraordinary states of spiritual realization?

If contemporary Western disciples, apparently engaging in the same practices as their Tibetan predecessors, are not gaining comparable realization, then one has to ask how these teachings and practices need to be modified in their format, in their sequence, in their context. To what extent do the theories need to come into dialogue with Western worldviews? This is something relatively few Tibetan lamas are doing to any significant extent—drawing the presentation of Buddhist views, meditation, and way of life into dialogue with Western scientific, religious, and philosophical views, values, ways of life. We do have a civilization here, after all. And to come over here as if we had no civilization at all, as if one were simply dropping the teachings into a cultural tabula rasa, is not reasonable. That is the other extreme, whose proponents declare, “We have the pure teachings!” and don’t even notice whether those so-called “pure teachings” are really producing good results, or whether they’re just producing a lot of fundamentalists who are rigid, arrogant, and elitist, declaring, “We have the only way!” To the extent that that’s happening in the West, it seems to me like a very quick way to turn Buddhism into a museum piece or worse.

To what extent is this actually happening?

To what extent is this actually happening?

I’m afraid it’s fairly common, especially in dharma scenes where the students are expected to listen quietly to the lamas’ teachings and accept and implement them without question. When students are given the impression that the lama is infallible and that any problem they experience or uncertainty they feel is only their fault, we have a recipe for fundamentalism. I have heard some avid dharma students respond to any objections to the orthodoxy of their dharma center with the one-liner, “But the lama says,” as if that is the one solution to all problems.

What’s in between the two extremes, then?

One solution is a close and respectful dialogue between Western disciples and Tibetan adepts. If they don’t already know the West, try to inform them about where they’re coming, and what kind of worldviews and values and way of life are considered the norm here. And where there’s resistance to receiving traditional Tibetan teachings, try to understand why there’s resistance, whether those teachings can be modified, or whether Westerners need some preliminary teachings prior to engaging in the more traditional teachings. Really bring in a lot of creativity.

Prior to the radical transformation caused by the Chinese invasion in 1949, changes in Tibetan society took place at a far slower pace than that of the modern West. They had a spiritual tradition that was turning out a significant number of accomplished contemplatives and scholars, so there was no need to be especially innovative. In that situation you would emphasize preservation of the tradition rather than ingenuity. But now, when the social context is changing so dramatically and rapidly for Buddhism in Asia, let alone for Buddhism in the West, there needs to be far more balance between preservation and intelligent adaptation, and Tibetans and Westerners need to discuss these things together.

Are Tibetan lamas in the West talking about this, asking questions about how effective their teachings have been?

There must be individual teachers, both Tibetan lamas as well as Western Buddhist teachers, who are paying attention to this. But I haven’t heard it very widely discussed. It’s a little bit of a delicate topic. If students are not deriving deep benefits from their Buddhist practice as taught to them according to Tibetan tradition, they are often told simply that the defect is in them and not in the teachings, which are pure and infallible. One alternative is not to conclude that the Buddha-dharma is defective, but to ask: Within the vast range of practices taught by the Buddha and later Indian and Tibetan adepts, which ones and which sequence of practices might be especially emphasized for Western students so that they are of optimal benefit?

To pursue this question we need to reintroduce a strong element of empiricism and pragmatism, which is perfectly consonant with the Buddha’s own teachings. And what really helps to purify your mind so that your mental afflictions are attenuated, so that you find greater contentment, greater serenity, greater wisdom, and greater compassion? What really works?

You once said that it is essential for the health of a religion, Buddhism especially, to continually produce professional contemplatives—those totally dedicated to the contemplative life. Why is this important?

The Dalai Lama commented on one occasion that in Buddhism, extraordinary claims are made about the potentials of human consciousness, about accomplishments that have been made by contemplatives in the past—including the achievement of meditative concentration, contemplative insights, and a wide range of paranormal abilities culminating in enlightenment itself. The Dalai Lama likened such accounts to paper currency, which is worth something if people are confident there’s a gold standard behind it. The “gold standard” of the paper currency of such Buddhist claims is people in the present generation achieving similar states of realization.

Even if only one-tenth of one percent of the Buddhist population gains such profound realization, this means you have at least a few individuals in each generation who have achieved the gold standard for the teachings. Well, if you’ve got a half dozen people in a Buddhist community at any one time who have achieved deep samadhi, display remarkable abilities as a result of their contemplative realizations, and finally achieve the rainbow body when they die, leaving only their hair and nails behind, that’s pretty compelling! So if we are going to arouse our inspiration to accomplish such heights of realization, we need people who are living examples. We don’t have many examples of Westerners, and one can ask if there are any at all who have achieved some of these advanced states of realization. And as the older lamas are passing away, one may wonder whether there are now Asian contemplatives who have achieved those states. If not, the paper currency of Buddhism is going to look more and more like Confederate currency.

To maintain the integrity of the Buddhist teachings, we need both professional scholars and contemplatives—those who are devoting themselves full-time, with pure motivation, to sustained study and meditative practice. Not just for months at a time, but for life. And the Buddhist lay public needs to dedicate itself to supporting monks, nuns, and serious lay practitioners who are willing to make such a commitment. This has been a key element to Buddhism flourishing in Asia, and it’s a mistake to think that it will flourish in the West without similar commitment on the part of teachers, students, and the Buddhist community at large.

At this point, what’s your own sense of what might work?

As I commented before, we in the West are living in a non-contemplative society in which there is little or no theoretical, practical, or social context for deep Buddhist practice. But many people are interested to know more about Buddhism, and of course they would like to do this as efficiently as they can. To my mind, this suggests the need for educational centers that offer sustained, rigorous instruction in various elements of Buddhist philosophy, psychology, ethics, meditation, and so on. And such teachings should be offered in dialogue with, or at least with a sensitivity toward, related themes in Western civilization. Second, there need to be contemplative training centers that are designed to offer a conducive environment for sustained, rigorous practice. And in such centers we could also draw on the strengths of our Western traditions, of psychology and so on, to observe carefully whether the practices are proving to be beneficial in the ways for which they were designed. If so, great! If not, then in close dialogue with Tibetan adepts, we need to see how the practices might be modified for Westerners so that they can produce the desired transformations and insights. We can enter into such an enterprise with a spirit of adventure. If we choose, we can accept on faith the extraordinary claims of Buddhist adepts about the nature and potentials of consciousness. But then, instead of leaving our faith as a dogmatic belief, we can use it as a working hypothesis as we put it to the test of experience. What greater adventure is there than the exploration of the depths of consciousness!

Where do you think all this is heading?

If the commercialization of Buddhism continues, and with it the loss of much of its extraordinary intellectual and contemplative rigor, then Tibetan Buddhism runs the danger of losing its integrity in the West and being totally assimilated into an amorphous New Age culture. On the other hand, I do see an open-mindedness, sincerity, and a vigorous spirit of inquiry among many Tibetan Buddhists in the East and West that inspire hope that this spiritual tradition is undergoing a vital renaissance. Perhaps its finest hour lies in the future. Which way it develops remains to be seen. It’s in our hands. ▼

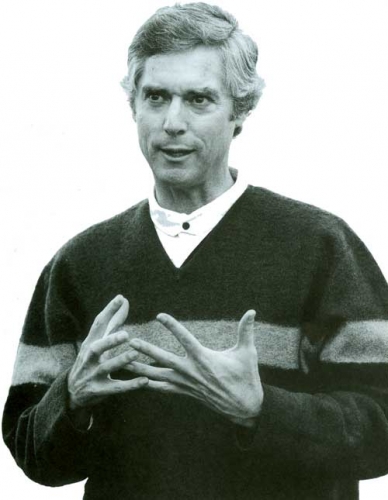

Images from top to bottom: photograph of B. Alan Wallace © Rikka Zimmeman; B. Alan Wallace, during his time as a monastic, speaks with His Holiness the Dalai Lama at Amherst College, in Massachusettes, 1984 © C. Hardin, courtesy of B. Alan Wallace; Eleven-Headed, One Thousand-Armed Avalokiteshvara, central Tibet, mid-twelfth century, distemper on cloth, private collection © John Bigelow Taylor.

Faith

An excerpt adapted from Buddhism with an Attitude by B. Alan Wallace

The Buddha himself, as well as contemporary, authentic Buddhist teachers, do not present themselves as unquestionable authorities on the nature of reality, nor as masters who instruct us infallibly on how to lead our lives. These teachers offer themselves to us above all as friends, specifically as spiritual friends, and as guides to lead us on an experiential journey in the pursuit of knowledge and personal transformation. But when we first meet them, they are strangers, and it is perfectly appropriate to respond to their teachings with agnosticism and skepticism. After all, when assuming a stance of agnosticism, we are quite realistically acknowledging that we don’t know the first step toward wisdom! And by taking a position of skepticism, we are in effect saying, “I doubt that you know either.” Considering the wide range of authoritative claims being made today about everything from the nature of consciousness to UFOs, in many cases such skepticism has to be well founded.

But if we want to make genuine discoveries about matters that are of life-and-death importance to us, we have to move beyond agnosticism. If we are totally convinced that no one else has discovered what we want to know, then we have no one to rely on but ourselves. If we are to be skeptical, surely we should start by being skeptical about how much we know about how much everyone else knows! If I’m really agnostic, I have to start with the premise that I don’t know whether you might have made important discoveries that I have not. Likewise, just because our Western civilization is ignorant in some respects, it would be silly to assume that no other civilization has made important discoveries where we have not.

When it comes to knowledge, Western civilization has made enormous strides, especially since the Scientific Revolution. We can take great pride and satisfaction in our many discoveries concerning the world around us. But one domain of reality in which we still remain scientifically in the dark is the realm of consciousness. It’s just not science’s strong point. However, precisely where science is at its weakest, the Buddhist tradition makes its strongest and most astonishing truth-claims. The only way we know of the existence of consciousness is by means of our first-person experience, and the Buddhist tradition has devised many ingenious methods for enhancing and refining this mode of perception so that we can probe more deeply into the nature, origins, and potentials of consciousness. In any early account of the Buddha’s life and teachings, it is obvious that he claimed to have made bold discoveries based on his own meditative experience. If you read how he responded to many of the metaphysical assertions of his time, it becomes obvious that he wasn’t one for simply adopting wholesale the beliefs of his contemporaries.

For example, the earliest account of his enlightenment makes it clear that his claims about the reality and significance of the continuity of individual consciousness after death were based on his own experiential knowledge. In evaluating his claims, we may conclude that he was right or that he was wrong, but there is nothing to imply that he was agnostic or that he lifted these ideas from someone else. His assertions about rebirth and karma were unique in his time. One of his remarkable claims that was inspired initially by other contemplatives is that the scope and precision of mental perception can be enormously enhanced by training in meditative concentration. In a broader sense, he claimed that the mental afflictions that beset us—such as hostility, craving, anxiety, and delusion—are not immutable. With training they can be attenuated, and with deep training, they can be eliminated completely. How do we know whether he knew what he was talking about? Simply put, we don’t. We start out as agnostics. But if we want to find out, the only way to proceed is to put the training to the test of our own experience. Here is a time not for skepticism, but for intelligent faith.

When we first meet the Buddha indirectly (through his teachings) or a contemporary Buddhist teacher directly, we are meeting with a stranger. But if we cultivate the relationship, over time, the teacher becomes a friend on whom we can rely for matters that are presently beyond our ken. After getting to know a specific Buddhist teacher, if we find him untrustworthy or unhelpful, then we are free to choose another teacher. A number of my lamas have commented after giving public teachings, “If you find these teachings to be sound and useful, by all means put them into practice. If not, keep on looking!”

At the same time, we need to apply discerning intelligence to our own way of putting the teachings to the test. Do questionable Buddhist truth-claims violate reason or compelling empirical evidence? Or do they just violate our assumptions and what the people around us think? What do we really know, and what have we picked up as untested assumptions and preconceptions from our society? This is a time for self-directed skepticism. And if we put the teachings into practice and find them ineffective, where does the inadequacy lie: in the teachings or in our own implementation of them? For example, the Buddha and many later Buddhist contemplatives claim to have achieved irreversible freedom from various mental afflictions. If we fail to do so, what have we proven? That they didn’t either, or simply that we did not practice with sufficient diligence and intelligence?

The Buddha is like one who swims out to meet us and shows us the way to shore. He says he has been there, and many discoveries lie in wait for us on land if we will let go of the buoy of our uncertainty, our faint-heartedness, and our skepticism. Of course, there is nothing to compel us to place our trust in him or in any later Buddhist teacher. We can remain agnostic and skeptical as long as we like. But if we choose to accept the challenge of the Buddhist path of contemplative exploration, we need to let go of our insecurities and take the plunge into practice. And this requires that we accept some of the Buddha’s assertions on faith as working hypotheses. The Buddhist tradition speaks of three kinds of faith, and this is the first kind: the faith of belief.

Reprinted by permission of Snow Lion Publications

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.