Nine hundred years ago, the Korean peninsula was under siege. From their northern homelands, barbarian tribes known as the Khitans raided cities and towns, laying waste to countless Korean lives. The Korean military successfully repulsed the invaders for decades, but the continued incursions forced King Hyonjong, who ruled between 1010 and 1039, to exhaust every defensive alternative. Hopelessly outnumbered and facing military instability at home, Hyonjong concluded that his kingdom’s fate lay not in his own hands but in those of a higher power.

In 1011, in an effort to secure the protection of the Buddha for his kingdom and people, King Hyonjong ordered the compilation and carving in wood of the entire Korean Buddhist canon. The result of this meritorious work was called Pal Man Dae Jang Kyung, or “The Great 80,000 Hidden Sutras.” Westerners have labeled it the Tripitaka Koreana.

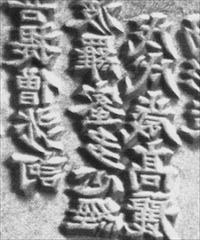

The king reorganized the priesthood and ordered them to collate and translate all available Buddhist writings from China. This was a monumental undertaking for Korean monks, for it was the first time that the entire known Buddhist canon was committed to written form. Scholars now believe that the format and calligraphy of the Tripitaka Koreana were actually modeled after those now-extinct Chinese works, but the Korean version was said to have surpassed all its predecessors in precision and beauty.

The wooden printing blocks were completed some two decades after they were started. For storage and safekeeping, monks transported them to Puin-sa, a small temple near Taegu. Although the Tripitaka had been finished, the king was bewildered because peace still had not descended upon his kingdom: Khitan raiders continued to attack Korea both directly, with organized troops, and indirectly, when refugees fleeing the Mongols left a path of destruction through Korea. The Khitans actually continued to lay siege to the peninsula until a Mongolian cavalry force stamped them out in northern Korea in 1218.

Yet amid the carnage of war and the destruction of many religious and historical structures, the blocks somehow escaped harm. The Tripitaka survived nearly two centuries, until a new wave of invaders—this time the Mongols—took their turn at plundering Korea. Mongol raiders torched all 80,000 carved blocks along with the temple that housed them. No printed copies are known to have survived.

Subsequent Mongol invasions spread through China and again buffeted Korea, now without the Tripitaka for protection. The situation worsened when, in 1227, Genghis Khan died and his successor, Ogodei, resolved to conquer Korea. His cavalry incursions commenced in 1231 and proved so devastating that, once again, few possibilities for resistance presented themselves to the Koreans.

Again the ruling monarch turned to the Buddha for help. King Kojong, who reigned from 1213 to 1259, ordered the creation of a duplicate set of printing plates in 1236, again to be produced by native artisans and literate Buddhist monks. Earlier, King Kojong had been forced to relocate his capital from Kaesong to the relative security of Kanghwa-do, an easily defended island some twenty miles to the west. There, at a temple called Ch’ondeung-sa, he oversaw the project for some sixteen years.

The Mongol occupation forces felt no immediate effect that might prove the Buddha was actually aiding the Koreans. Mongol power in Korea eventually did start to wane in the 1350s, however, and terminated altogether in 1381 when the Yuan dynasty was overthrown by the Chinese Ming.

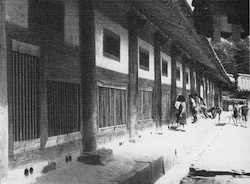

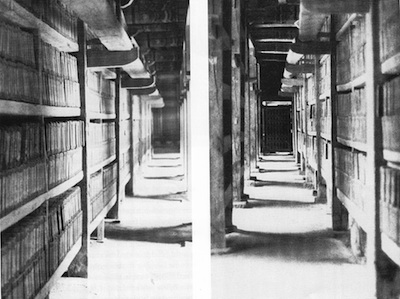

Unlike the first version of the Tripitaka, the second survived centuries of devastation. In fact, records show that since the creation of the second Tripitaka, not a single block has decayed or been destroyed. They are still housed in their entirety in Haein-sa, a remote temple in Korea.

Uncertainties remain about the exact process used to create the Tripitaka Koreana, but scholarly consensus favors the following. First, suitable specimens of the silver magnolia tree were located on the islands off the southern coast of the country. Workers felled the trees and chopped them into smaller chunks for the journey up the west coast and across the strait to Kanghwa-do and Ch’ondeung-sa. At the monastery, the raw materials were soaked in sea water for three years, after which they were immersed in fresh water for another three years. The slabs were then allowed to dry in the open air but were always protected from direct sunlight.

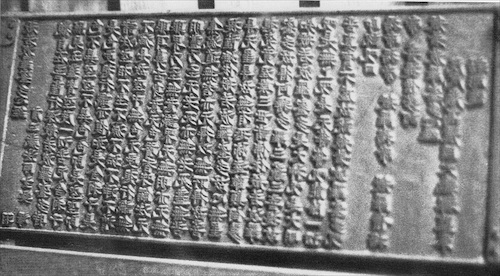

Skilled craftsmen trimmed and carved the slabs, carving each intricate character in reverse. A natural lacquer concocted from a Korean folk recipe preserved the wood and repelled insects. Finally, a narrow metal plate affixed to the edge of each block strengthened it against splitting and provided information about its contents and volume number in the sequenced set. The 81,340 finished blocks (some sources say 81,258) were arranged into 6,708 volumes in 1,501 categories. Each was engraved on both sides with an average of 322 characters per side, arranged in 234 lines of 14 characters.

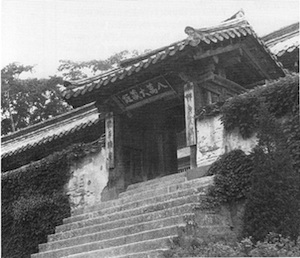

In 1399, monks spirited all but 121 blocks southward from Ch’ondeung-sa to a safer location. The monks feared that if invaders ever located the new blocks, they would again set fire to them. The priests chose as a safehouse a monastery in Kyongsangnam-do province. Although the compound was called Haein-sa, “Reflections of the Sea Temple,” it lay in a secluded valley far from the sea coast or any other potential invasion route.

Haein-sa was founded in 805 by two monks named Ich’ong and Sonung. Legend has it that they were called upon to heal the queen, who had been stricken with an incurable disease. Utilizing the Buddhist healing methods they had recently learned in China, the monks gave her only a length of thread. They advised her to tie one end around her finger and the other around a pear tree in the courtyard. As the tree withered and died, the queen regained her strength and eventually recovered. In appreciation, she ordered the construction of Haein-sa to propagate the miraculous teachings of the Buddha.

Today, Haein-sa exists almost exactly as it did when it was built as a center for Hwaom (Huayen) Buddhism nearly twelve centuries ago. It was one of the very few religious structures to escape destruction by marauding Japanese forces during the Hideyoshi invasions of 1592. The temple now sits near the modern city of Hapch’on, at the foot of Gaya-san, a mountain some say is named after Bodhgaya in India.

Recently, the Korean government designated Haein-sa and the Tripitaka Koreana as “Natural Monument Number 32” and “National Treasure Number 206,” respectively, officially adding historical worth to their religious value. Because of the Tripitaka, Haein-sa is now considered one of Korea’s three holiest Buddhist temples, and an embodiment of the Three Jewels of Buddhism—the Buddha, the dharma, and the sangha—both in spirit and in the tangible reality of the Tripitaka itself.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.