Enjoy these walking meditation instructions from nine teachers and authors.

Achaan Chah

A contemporary Thai teacher on cultivating mindfulness through walking meditation.

Work with the walking meditation every day. To begin, clasp the hands in front of you, maintaining a very slight tension that compels the mind to be attentive. Walk at a normal pace from one end of the path to the other, knowing yourself all the way. Stop and return. If the mind wanders, stand still and bring it back. If the mind still wanders, fix attention on the breath. Keep coming back. Mindfulness thus developed is useful at all times.

Change positions when physically tired, but not as soon as you feel an impulse to change. First, know why you want to change—is it physical fatigue, mental restlessness, or laziness? Notice the sufferings of the body. Learn to watch openly and carefully. Effort in practice is a matter of the mind, not the body. It means constantly being aware of what goes on in the mind without following like and dislike as they arise. Sitting or walking all night is not in itself energetic effort if one is not aware in this way.

As you walk from one predetermined point to another, fix the eyes about two yards in front of you and fix the attention on the actual feeling of the body, or repeat the mantra “Buddho.” Do not fear things that arise in the mind; question them, know them. The truth is more than thought and feelings, so do not believe and get caught by them. See the whole process arising and ceasing. This understanding gives rise to wisdom.

When consciousness arises, we should have awareness of it at the same time, like a light bulb and its light. If you are not alert, the hindrances will catch hold of the mind—only concentration can cut through them. Just as the presence of a thief prevents negligence with our possessions, so the reminder of the hindrances should prevent negligence in our concentration.

♦

From A Still Forest Pool: The Insight Meditation of Achaan Chah, compiled and edited by Jack Kornfield and Paul Breiter, reprinted with permission from Theosophical Publishing House.

Sylvia Boorstein

An American teacher of Insight Meditation offers basic instruction.

Pick a place to walk back and forth that is private and uncomplicated—one where the walking path can be ten to twenty feet long. If you walk outdoors, find a secluded spot so that you won’t feel self-conscious. If you walk indoors, find a furniture-free section of your room or an empty hallway. Then you can devote all your attention to the feelings in your feet as you walk.

Keep in mind that this is attentiveness practice and tranquillity practice, not specialty walking practice. You don’t need to walk in any unusual way. No special balance is needed, no special gracefulness. This is just plain walking. Perhaps at a slower pace than normal, but otherwise, quite ordinary.

Begin your period of practice by standing still for a few moments at one end of your walking path. Close your eyes. Feel your whole body standing. Some people start by focusing their attention on the top of the head, then move their attention along the body through the head, shoulders, arms, torso, and legs, and end by feeling the sensations of the feet connecting with the earth. Allow your attention to rest on the sensations in the soles of the feet. This is likely to be the feeling of pressure on the feet and perhaps a sense of “soft” or “hard,” depending on where you are standing.

Begin to walk forward. Keep your eyes open so that you stay balanced. I often begin with a normal strolling pace and expect that the limited scope of the walk, and its repetitious regularity, will naturally ease my body into a slower pace. Slowing down happens all by itself. I think it happens because the mind, with less stimuli to process, shifts into a lower gear. Probably the greed impulse, ever on the lookout for something novel to play with, surrenders when it realizes you’re serious about not going anywhere.

When you walk at a strolling pace, the view is panoramic and descriptive. When your walking slows, the view is more localized and subjective. If we could see running readouts, like subtitles, of the mental notes that accompany walking, they might look like this:

Strolling pace: “Step . . . step . . . step . . . step . . .

arms moving . . . head moving . . . smiling . . . looking . . .

stopping . . . turning . . . bird chirping . . .

stepping . . . stepping . . . wondering what time it is . . .

thinking this is boring . . . stepping . . . stepping . . .

swinging arms . . . feeling warm . . .

feeling cool . . . I’m glad I’m in the shade . . .

deciding to stay in the shade . . . smiling . . . stepping . . .”

Slower pace: “Pressure on feet . . . pressure . . . pressure disappearing . . .

pressure reappearing . . . pressure shifting . . .

lightness . . . heaviness . . . lightness . . . heaviness . . . lightness . . .

Hey! Now I’ve got it! Now I’m finally present!. . .

Whoops, I’ve been distracted . . . Start again . . .

Pressure on feet . . . pressure shifting . . . lightness . . .

heaviness . . . lightness . . . heaviness . . .

hearing . . . warm . . . cool . . .”

Slow is not better than fast. It’s just different. Everything changes, regardless of pace, and direct firsthand experience of temporality can happen while you are strolling just as much as while you are stepping deliberately and slowly. The speed-limit guide for mindful walking is to select the speed at which you are most likely to maintain attention. Shift up or down as necessary.

Now, try a period of walking meditation. Start with thirty minutes. If you [have] a timer with a pleasant “ding,” set the timer and begin. If your watch has an alarm, you can use it as a timer. As you walk note how many times the impulse to check the time arises. Don’t do it. Just walk. This way, in addition to composure and attentiveness, you get to practice renunciation, a fundamental factor in awakening.

♦

Excerpted from Don’t Just Do Something, Sit There, reprinted with permission from HarperSanFrancisco.

Hakuun Yasutani Roshi

A Japanese Zen master on kinhin, the formal walking meditation practiced in Zen monasteries.

In terminating a period of sitting do not rise abruptly, but begin by rocking from side to side, first in small swings, then in large ones, for about half a dozen times. You will observe that your movements in this exercise are the reverse of those you engage in when you begin zazen. Rise slowly and quietly walk around with the others in what is called kinhin, a walking form of zazen.

Kinhin is performed by placing the right fist, with thumb inside, on the chest and covering it with the left palm while holding both palms at right angles. Keep the arms in a straight line and the body erect, with the eyes resting on a point about two yards in front of the feet. At the same time continue to count inhalations and exhalations as you walk slowly around the room. Begin walking with the left foot and walk in such a way that the foot sinks into the floor, first the heel and then the toes. Walk calmly and steadily, with poise and dignity. The walking must not be done absent-mindedly, and the mind must be taut as you concentrate on the counting. It is advisable to practice walking this way for at least five minutes after each sitting period of twenty to thirty minutes.

You are to think of this walking as zazen in motion. Rinzai and Soto [the two main schools of Japanese Zen] differ considerably in their way of doing kinhin. In the Rinzai method the walking is brisk and energetic, while in the traditional Soto it is slow and leisurely; in fact, upon each breath you step forward only six inches or so. My own teacher, Harada-roshi, advocated a gait somewhere between these two and that is the method we have been practicing here. Further, the Rinzai sect cups the left hand on top of the right, whereas in the orthodox Soto the right hand is placed on top.

Harada-roshi felt that the Rinzai method of putting the left hand uppermost was more desirable and so he adopted it into his own teaching. Now, even though this walking relieves the stiffness in your legs, such exercise is to be regarded as a mere by-product and not the main object of kinhin. Hence those of you who are counting your breaths should continue during kinhin, and those of you who are working on a koan should carry on with it.

♦

Excerpted from Three Pillars of Zen, edited by Philip Kapleau, reprinted with permission from Weatherhill, Inc.

Jon Kabat-Zinn

A stress reduction specialist on being where you are.

I know people who at one time found it very difficult to sit but got deeply into meditation practice through walking. No matter who you are, you can’t sit still all the time. And some people just find it virtually impossible to stay seated and mindful with the levels of pain and agitation and anger they feel. But they can walk with it.

In traditional monastic settings, periods of sitting meditation are interspersed with periods of walking meditation. They are the same practice. The walking is just as good as the sitting. What is important is how you keep your mind.

In formal walking meditation, you attend to the walking itself. You can focus on the footfall as a whole; or isolated segments of the motion such a shifting, moving, placing, shifting; or on the whole body moving. You can couple an awareness of walking with an awareness of breathing.

In walking meditation, you are not walking to get anyplace. Usually it is just back and forth in a lane, or round and round in a loop. Literally having no place to go makes it easier to be where you are. What’s the point of trying to be somewhere else on your walking path when it really is all the same? The challenge is, can you be fully with this step, with this breath?

Walking meditation can be practiced at any pace, from ultra-slow to very brisk. How much of the foot cycle you can attend to will depend on the speed. The practice is to take each step as it comes and to be fully present with it. This means feeling the very sensations of walking—in your feet, in your legs, in your carriage and gait, as always, moment by moment, and in this case, step by step as well. You might call it “watching your step,” pun intended, although it is an inner watching. You’re not looking at your feet!

Just as in sitting meditation, things will come up which will pull your attention away from the bare experience of walking. We work with those perceptions, thoughts, feelings and impulses, memories and anticipations, that come up during the walking in the very same way that we do in sitting meditation. Ultimately, walking is stillness in motion, flowing mindfulness.

It’s best to do formal walking meditation in a place where you won’t become a spectacle to other people, especially if you are going to do it very slowly. Good places are your living room, fields, or a clearing in the woods; isolated beaches are good, too. Push a shopping cart in front of you through a supermarket and you can walk as slowly as you like.

You can practice walking meditation informally anywhere. Informal walking meditation doesn’t involve pacing back and forth or going around a loop, but just walking normally. You can walk mindfully along a sidewalk, down a corridor at work, going for a hike, walking your dog, walking with children. It involves recalling that you are here in your body. You simply remind yourself to be in this moment, taking each step as it comes, accepting each moment as it comes. If you find yourself rushing or becoming impatient, slowing the pace can help take the edge off your rushing and remind you that you are here now, and that when you get there, you will be there. If you miss the here, you are likely also to miss the there. If your mind is not centered here, it is likely not to be centered just because you arrive somewhere else.

♦

Excerpted from Wherever You Go There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life, by Jon Kabat-Zinn, reprinted with permission from Hyperion.

Thich Nhat Hanh

A Vietnamese Zen master on walking the path of self-realization.

In our daily lives, we usually feel pressured to move ahead. We have to hurry. We seldom ask ourselves where it is that we must hurry to.

When you practice walking meditation, you go for a stroll. You have no purpose or direction in space or time. The purpose of walking meditation is walking meditation itself. Going is important, not arriving. Walking meditation is not a means to an end; it is an end. Each step is life; each step is peace and joy. That is why we don’t have to hurry. That is why we slow down. We seem to move forward, but we don’t go anywhere; we are not being drawn by a goal. Thus we smile while we are walking.

In daily life, our steps are burdened with anxieties and fears. Life itself seems to be a continuous chain for insecure feelings, and so our steps lose their natural easiness.

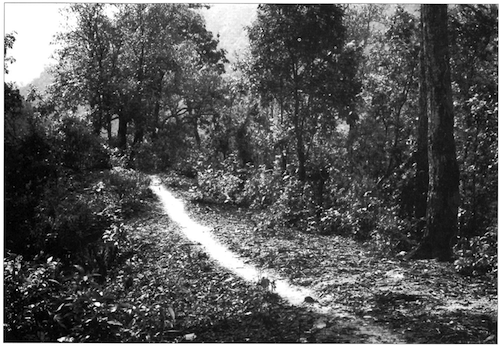

Our earth is truly beautiful. There is so much graceful, natural scenery along the paths and roads around the earth! Do you know how many dirt lanes there are, lined with bamboo, or winding around scented rice fields? Do you know how many forest paths there are, paved with colorful leaves, offering cool and shade? They are all available to us, yet we cannot enjoy them because our hearts are not trouble-free, and our steps are not at ease.

Walking meditation is learning to walk again with ease. When you were about a year old, you began to walk with tottering steps. Now, in practicing walking meditation you are learning to walk again. However, after a few weeks of practice, you will be able to step solidly, in peace and comfort.

Choose a nice road for your practice, along the shore of a river, in a park, on the flat roof of a building, in the woods, or along a bamboo fence. Such places are ideal, but they are not essential. I know there are people who practice walking meditation in reformation camps, even in small prison cells.

It is best if the road is not too rough or too steep. Slow down and concentrate on your steps. Be aware of each move. Walk straight ahead with dignity, calm, and comfort. Consciously make an imprint on the ground as you step. Walk as the Buddha would. Place your foot on the surface of the earth the way an emperor would place his seal on a royal decree.

A royal decree can bring happiness or misery to people. It can shower grace on them or it can ruin their lives. Your steps can do the same. If your steps are peaceful, the world will have peace. If you can take one peaceful step, you can take two. You can take one hundred and eight peaceful steps.

I suggest that you should walk like a Buddha, taking steps as the Buddha did. Each step leaves the imprint of peace, joy and innocence on the surface of the earth, and the earth becomes the Pure Land.

It is not by preaching or expounding the sutras (scriptures) that you fulfill the task of awakening others to self-realization; it is rather by the way you walk, the way you stand, the way you sit and the way you see things.

♦

Excerpted from The Long Road Turns to Joy: A Guide to Walking Meditation, by Thich Nhat Hanh, reprinted with permission from Parallax Press.

Joan Halifax

On walking as a “message to Earth.”

In Buddhism, we practice aimlessness (apranahita), even in relation to our personal, social and environmental work. It means that we are not so purposive that we destroy the present moment. “What way from here?” poet Han Shan asks his shadow. Just this step. The path is every step. How can we stray from it?

One day when I was walking down the canyon path in Ojai [California], I realized that I was making a literal impression on the Earth. I stopped and turned around to look at my footprints and they were even and smooth, a kind of script in the dust. That was on Thursday. On Friday, I hurried to the office on the central part of the land and halfway there I caught myself, stopped and turned around to look at my tracks. There was a different message on the Earth. It was then that I saw how completely each step that we take is a message of alienation or awareness to Earth. And it is in the experience of walking that we can learn this truth.

In Zen Buddhist practice, walking in the zendo is a way for us to stitch together our awareness with the world. One Zen master compared walking to the fine sewing of a robe, each step perfect and complete, each step resolved. I like to dwell on this image of the robe because it brings up the sense of precision and harmony that mindfulness cultivates.

Many years ago, I hurried along a trail in a cedar forest on one of the San Juan Islands near Seattle to see whether it was appropriate for a meditation walk. Hours later when I made the walk with twenty others, the world that had disappeared as I hurried through it in the morning was fully present as we walked in slow and quiet steps.

When we walk slowly, the world can fully appear. Not only are the creatures not frightened away by our haste or aggression, but the fine detail of fern and flower, or devastation and disruption, becomes visible. Many of us hurry along because we do not want to see what is really going on in and around us. We are afraid to let our senses touch the body of suffering or the body of beauty.

Walking meditation, for the Buddhist, is a way for the mind of practice to be embodied. Sitting in silence, stopping the body, makes it possible for the breath, mind, and body to calm down and finally synchronize. This is the practice of meditative stabilization, of balance, of the middle way of nonduality and nonviolence. Koan 25 in the Blue Cliff Record says that “If you stick to a fixed position, you fall into a poison sea.” A fixed position here means a conceptual or physical position. But walking meditation teaches us to move along without losing our mind and losing our balance. It teaches us how to ground our awareness with each step that we take. Walking practice is a kind of medicine that heals the split we experience from the world.

Maps help us to find our way through the body of the world. There are many different kinds of maps. Some of them are found in myths where the sacred geographies mirror the human condition. Maps also can show us the way through and across Earth. There are maps for flying, maps for driving, and maps for walking. The topography of the worlds described in each of these maps becomes more detailed the slower you go.

Richard Baker Roshi once said that all we have in this world is what we notice. This statement reminds me of the story of the Australian Aboriginal man who, when riding along in a car with a friend, sang at top speed as his territory flew past him. The Songline [an oral map passed down from generation to generation] is to be followed at a walking pace. In this way, the continuum of ancestor and totem is confirmed in the movement of the walker and in the detail of Earth. The subtle and physical world combine in the song-body and enhance one another. The experience of walking makes it possible to notice and become intimate with what is really there.

Bruce Chatwin

On the origins of human restlessness.

I had a presentiment that the “traveling” phase of my life might be passing. I felt, before the malaise of settlement crept over me, that I should reopen those notebooks. I should set down on paper a résumé of the ideas, quotations and encounters which had amused and obsessed me; and which I hoped would shed light on what is, for me, the question of questions: the nature of human restlessness.

Pascal, in one of his gloomier pensées, gave it as his opinion that all our miseries stemmed from a single cause: our inability to remain quietly in a room.

Why, he asked, must a man with sufficient to live on feel drawn to divert himself on long sea voyages? To dwell in another town? To go off in search of a peppercorn? Or to go off to war and break skulls?

Later, on further reflection, having discovered the cause of our misfortunes, he wished to understand the reason for them. He found one very good reason: namely, the natural unhappiness of our weak mortal condition; so unhappy that when we gave to it all our attention, nothing could console us.

One thing alone could alleviate our despair, and that was “distraction” (divertissement): yet this was the worst of our misfortunes, for in distraction we were prevented from thinking about ourselves and were gradually brought to ruin.

Could it be, I wondered, that our need for distraction, our mania for the new, was, in essence, an instinctive migratory urge akin to that of birds in autumn?

All the Great Teachers have preached that Man, originally, was a “wanderer in the scorching and barren wilderness of this world”—the words are those of Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor—and that to rediscover his humanity, he must slough off attachments and take to the road.

My two most recent notebooks were crammed with jottings taken in South Africa, where I had examined, at first hand, certain evidence on the origin of our species. What I learned there—together with what I now knew about the Songlines—seemed to confirm the conjecture I had toyed with for so long: that Natural Selection has designed us—from the structure of our brain-cells to the structure of our big toe—for a career of seasonal journeys on foot through a blistering land of thorn-scrub or desert.

If this were so; if the desert were “home”; if our instincts were forged in the desert; to survive the rigors of the desert—then it is easier to understand why greener pastures pall on us; why possessions exhaust us, and why Pascal’s imaginary man found his comfortable lodgings a prison.

♦

Excerpted from The Songlines, reprinted with permission from Penguin Books.

Henry David Thoreau

On sauntering.

I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks—who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering: which word is beautifully derived “from idle people who roved about the country, in the Middle Ages, and asked charity, under pretense of going à la Sainte Terre,” to the Holy Land, till the children exclaimed, “There goes a Sainte-Terrer, a Saunterer, a Holy-Lander. They who never go to the Holy Land in their walks, as they pretend, are indeed mere idlers and vagabonds; but they who do go there are saunterers in the good sense, such as I mean. Some, however, would derive the word from sans terre, without land or a home, which, therefore, in the good sense, will mean, having no particular home, but equally at home everywhere.

For this is the secret of successful sauntering. He who sits still in a house all the time may be the greatest vagrant of all; but the saunterer, in the good sense, is no more vagrant than the meandering river, which is all the while sedulously seeking the shortest course to the sea. But I prefer the first, which, indeed, is the most probable derivation. For every walk is a sort of crusade, preached by some Peter the Hermit in us, to go forth and reconquer this Holy Land from the Infidels.

It is true, we are but faint-hearted crusaders, even the walkers, nowadays, who undertake no persevering, never-ending enterprises. Our expeditions are but tours, and come round again at evening to the old hearth-side from which we set out. Half the walk is but retracing our steps. We should go forth on the shortest walk, perchance, in the spirit of undying adventure, never to return, – prepared to send back our embalmed hearts only as relics to our desolate kingdoms. If you are ready to leave father and mother, and brother and sister, and wife and child and friends, and never see them again, – if you have paid your debts, and made your will, and settled all your affairs, and are a free man, then you are ready for a walk.

♦

From the essay Walking, reprinted from its posthumous first publication in the June 1862 issue of The Atlantic Monthly.

Matsuo Basho

The seventeenth century haiku poet of Japan on a life of traveling.

The moon and sun are eternal travelers. Even the years wander on. A lifetime adrift in a boat, or in old age leading a tired horse into the years, every day is a journey and the journey itself is home. From the earliest times there have always been some who perished along the road. Still I have always been drawn by windblown clouds into dreams of a lifetime of wandering.

Coming home from a year’s walking tour of the coast last autumn, I swept the cobwebs from my hut on the banks of the Sumida just in time for New Year, but by the time spring mists began to rise from the fields, I longed to cross the Shirakawa Barrier into the Northern Interior. Drawn by the wanderer-spirit Dosojin, I couldn’t concentrate on things. Mending my cotton pants, sewing a new strap on my bamboo hat, I daydreamed. Rubbing moxa into my legs to strengthen them, I dreamed a bright moon rising over Matsushima. . .

Very early on the twenty-seventh morning of the third moon, under a predawn haze, transparent moon still visible, Mount Fuji just a shadow, I set out under the cherry blossoms of Ueno and Yanaka. When would I see them again? A few old friends had gathered in the night and followed along far enough to see me off from the boat. Getting off at Senju, I felt three thousand miles rushing through my heart, the whole world only a dream. I saw it through farewell tears.

Spring passes

and the birds cry out—

tears in the eyes of fishes

With these first words from my brush, I started. Those who remain behind watch the shadow of a traveler’s back disappear.

♦

Excerpted from Narrow Road to the Interior, translated by Sam Hamill, reprinted with permission from Shambhala Publications.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.