Two years ago Karl messaged me on Twitter. He had read my books. He too lived in Vienna. He wanted to buy me a beer at a famous socialist pub. He seemed odd and grumpy, like I owed him money, even though we’d never met. I’ve since discovered that saying someone is odd and grumpy is just another way of saying they’re Austrian. We’ve become good friends.

I recently learned that his daughter was born on his living room rug. Not by choice. It was a quick birth. When the thing began to happen, Karl bolted out the front door and scoured his apartment complex looking for a doctor. He found a veterinarian instead.

I guess Karl needed to let off some steam after his firstborn splashed out right there on the Ikea rug. However, he did not drink a glass of wine, play Minecraft, or smoke a clove cigarette. He waited for his wife and their new baby to fall asleep. Then he buzzed his in-laws into the apartment building and headed straight to the nearest Thalia bookstore.

“I believe that books find you; you don’t find them,” he told me. “Your book Zen Confidential was sitting right there on the shelf. The spine was staring at me. Just a few hours after my daughter was born. Isn’t that strange? Don’t you think that means something?”

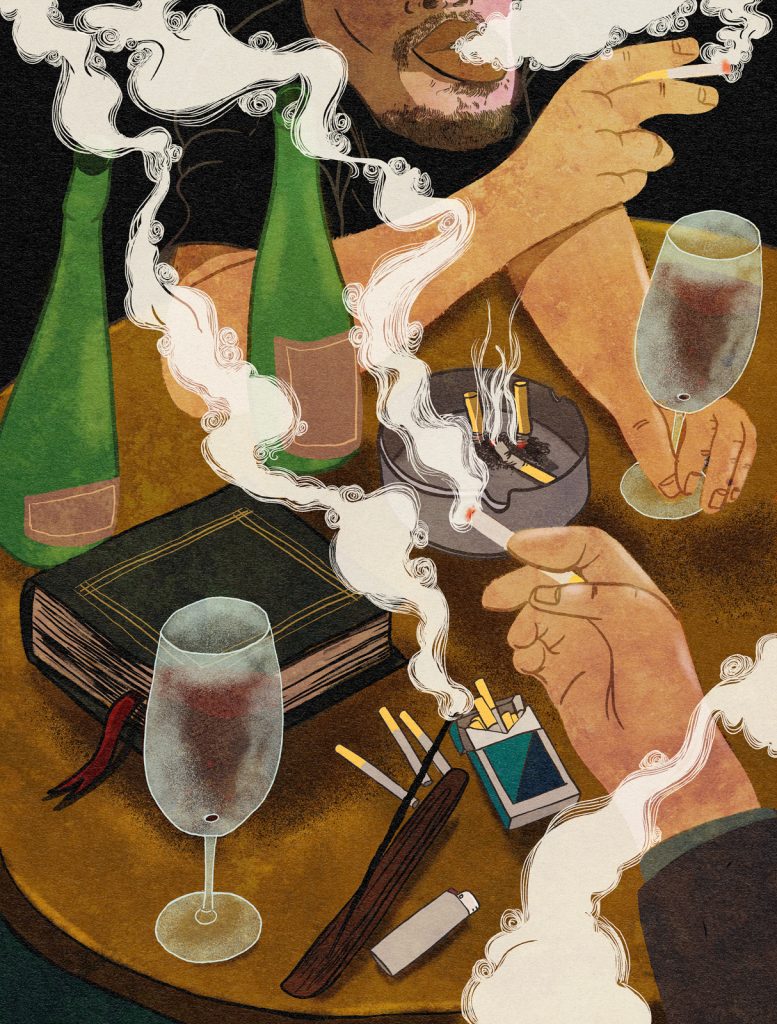

I’d set up two chairs in my hallway. There was a glass bedside table between us. We were sitting in front of a bottle of wine in my Spartanly furnished apartment.

I’m not sure what Karl’s relationship with alcohol is, but the two of them seem close. I prepared for his visit by buying a bottle of chardonnay and securing a decanter of my girlfriend’s father’s homemade plum schnapps. Karl brought a bottle of burgundy. Within the hour the first wine bottle was in my recycling bag, empty; the second bottle was half empty, and our tongues were loose and tingling.

He got to the point.

“You studied with a great Zen master from Japan. You spent thirteen years as a monk. Now look at you! What are you doing with yourself? Writing a novel?”

He made an Austrian noise, something like a snort and a snarl that signaled disappointment. “I feel like you could write the book.”

This got my attention. “What book?”

“The book I’ve been waiting for my whole life,” he shouted, as though this settled it.

His eyes were sparkling, but they were also a little angry. He sat there beaming foully at me, and I took the opportunity to admire his wardrobe: a stylish tweed flat cap and a dark blue sport coat. European men really know how to stick their sartorial landings. They even iron their shirts before going to the grocery store.

“I read everything,” Karl said. “I’ve always felt I will read my way to the truth.”

I offered him some Zen babble about how the truth can’t be contained in words. “I know this,” he growled. “But still. I’ve always felt you would write that book. Now you’re working on a novel you don’t even like.” He wiped his hand across his face to get rid of his ornery smile.

Silver lining in an overall dark cloud—that’s the basic Austrian temperament. I spent twenty-two years in California. The basic temperament there is Eternal Sunshine of the Idiotic Mind. A Californian and a Viennese meet. Sparks will fly!

He went to take a leak.

I tried to process the evening so far.

I had written my two books for precisely this kind of person. Someone spiritually thirsty yet suspicious of religion. Someone whose intelligence manifests as greater and greater curiosity instead of greater and greater knowingness. Someone who is, like me, intellectually plain—or, as we like to think of ourselves, intuitive.

Now here he was, hopelessly disappointed in what I had become. I kind of liked it. I wasn’t pretending to be the witty, wise monk anymore. I was just a guy in the world with his head up his ass like everyone else.

The lighting is weird in my hallway. A single bulb hangs from the spacious Altbau ceiling. Granted, it’s a hip light bulb, big as a softball, connected to a fancy blue cord. But still. It felt like we were in an interrogation room.

Karl returned from the bathroom and wiped his wet hands on his jeans. “Get a towel, man,” he said.

His phone rang. He looked at it and put it face down on the table. It rang and rang.

“You want to get that?” I asked.

“Not a chance. It’s my father.”

We drank some more, working our way into my girlfriend’s dad’s high-powered homemade schnapps. There was a long stretch of silence, which I spent trying to taste the inside of my mouth, an old nervous habit. I could smell my deodorant working.

“I haven’t smoked in five years,” Karl said. “God, I love smoking. We should go out and get some cigarettes. You like cigarettes, don’t you?”

“You know I do,” I said.

By this point—the lighting, the booze, the disappointment—I’d come to feel like this guy was some kind of flesh-and-blood specter summoned by my dead Zen teacher to give me a post-monastery status report. He was challenging me, but in an Austro-friendly way.

The backstory here is that three months earlier he’d texted me from the freezing bowels of our European Pandemic Winter and asked me to be his Zen teacher. I could tell his texts were written with a drink in one hand.

“You didn’t blow me off,” he told me as we sat in my hallway. “You really took time to answer each question I had about Zen. But why won’t you be my teacher?”

He looked away, as though it were painful to behold me in my current form. He stared at the wall and shook his head. “Writing a Zen sci-fi novel, let me get this right, where the hero loses his virginity to a bioengineered version of himself? What are you doing?”

With the option of being my student off the table, he went out and got a shrink instead. Someone a decade younger than him, a recent graduate who used regression therapy to help him get through the dark winter months. Apparently they spent a lot of time surveying his current life from the perspective of his 12-year-old self.

I felt a little jealous. “Was she helpful?” I asked.

“Oh, very,” he said.

I wanted to cry.

But I cannot bear the thought of being anybody’s dharma teacher. It’s a thankless job and students have too many expectations. You put on the robes, and forget it. They want to screw you or fight you or spiritually outfox you or gossip about you. I was a Zen student for decades, after all. There’s no way I wanted Karl looking at me with the same “disappointment eyes” that I often gave senior Zen priests when they failed to meet my impossible standards.

Worse, though, is what the robes do to you.

Forget about cigarettes. The true addiction is to “monk junk.” The heroin of spiritual pride that sooner or later afflicts every professional cleric; the fantasy that you have special access to a universal truth, and therefore it is your guidance that stands between your student and the Goods.

“Therapy is important,” Karl said, letting me off the hook, “but it’s not the whole ball of wax.”

“Really?” I said.

I cannot bear the thought of being anybody’s dharma teacher. It’s a thankless job and students have too many expectations.

By now I’d begun to suspect that we both had something to offer each other. A teacher-student relationship was out of the question. But what if we could ride side by side into the satori sunset, like a Zen version of Butch and Sundance?

“Okay. Let’s Zoom later this week. We’ll sit together. I’ll show you how I meditate,” I told him. “That’s the best I can do.”

“Well, OK, if you insist,” he grumbled.

He stood up and put on his raincoat. His kicked his big feet into his patent leather shoes. In the doorway he held my gaze and said, “Thanks. I need it.”

Well, guess what, I realized, closing the door after him. Standing there. Listening to him clomp down the spiral stairwell. Who’d have thought?

I need it too.

He’s my sitting buddy now. He’s just begun his zazen practice, and I feel like I’m starting mine all over again. I’ve learned some interesting things too. I’ve learned that I know how to sit— I have the knowledge, I spent thirteen years at a Zen monastery, after all—but I don’t always put that knowledge into practice. And so when Karl asks me about meditation, I really listen—both to his questions and to my own answers.

Yesterday he texted me: “Breathing with the hara is quite difficult for me and doesn’t come naturally. I don’t know why.”

I sat down to see if breathing through the hara came naturally to me. I found that it both felt right and took some effort to do. I tried to think of similar situations in life where doing something felt both natural and tricky at the same time. Karl was helping me to think about Zen practice the only way one should ever think about it—from the perspective of a beginner.

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche once said that rather than look for a teacher, one should look for a spiritual friend. Someone to be with you as you practice. No one can teach you how to experience a sunset or fall in love. And no one can teach you how to meditate. You have to do it. The breath will show you the way.

Maybe it’s a bit like giving birth. Karl’s wife, God bless her, delivered their firstborn on the living room floor. She didn’t have a hospital. She didn’t have a doctor. She had a veterinarian and a bibliophile husband.

Just because something is natural, doesn’t mean it’s easy.

But she did it. Right there.

Right where Karl now sits, learning how to breathe.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.