Tricycle is pleased to offer the Tricycle Talks podcast for free. If you would like to support this offering, please consider donating. Thank you!

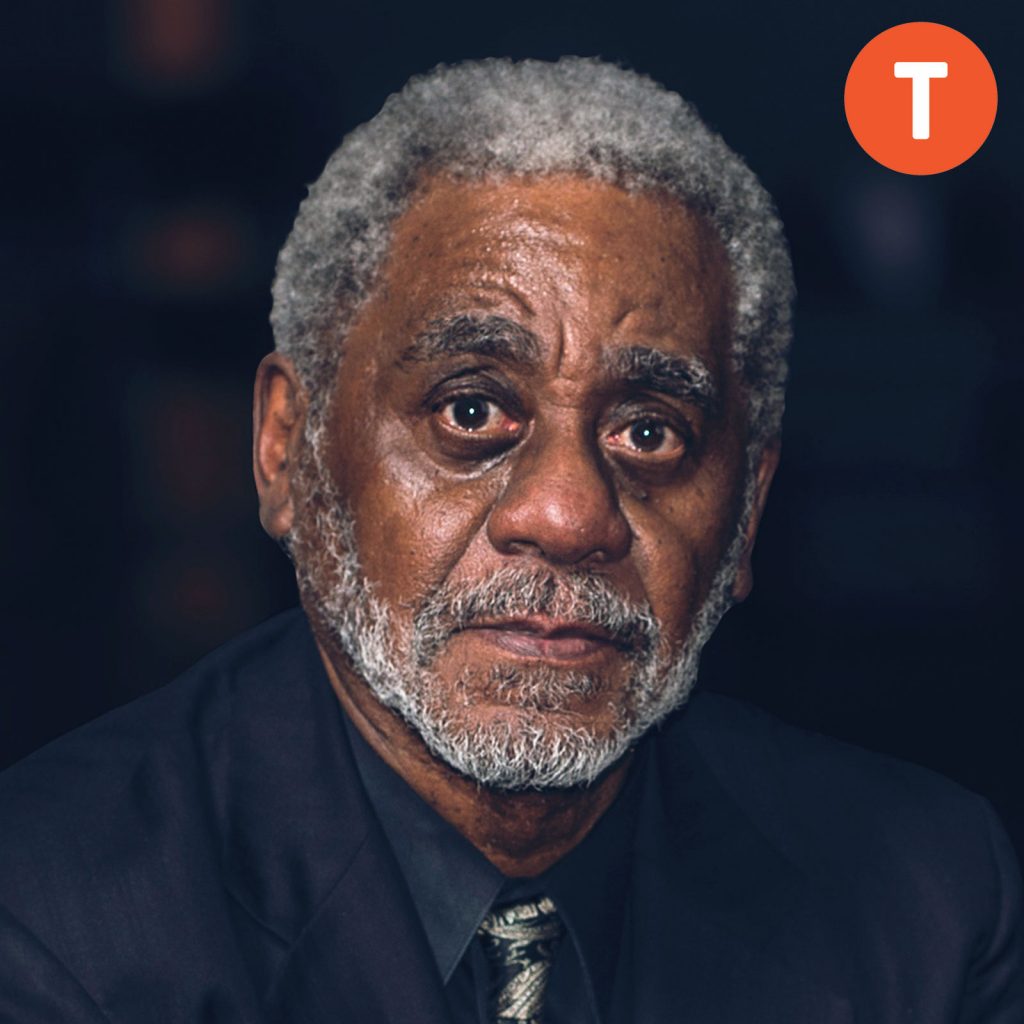

Charles Johnson is a novelist, essayist, screenwriter, professor, philosopher, cartoonist, and martial arts teacher—and he’s also a Tricycle contributing editor. Over the course of his career, he has published ten novels, three cartoon collections, and a number of essay collections that explore Black life in America, often through the lens of Buddhist literature and philosophy. In the February issue of Tricycle, Johnson wrote a contemporary retelling of a classic Zen tale called “Is That So?”

In this episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, sits down with Johnson to discuss his path to writing, how Buddhism finds its way into his work, and why he believes that art should liberate us from calcified ways of thinking and seeing.

Tricycle Talks is a podcast series featuring leading voices in the contemporary Buddhist world. You can listen to more Tricycle Talks on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, SoundCloud, Stitcher, and iHeartRadio.

♦

We’d love to hear your thoughts about our podcast. Write us at feedback@tricycle.org.

Read transcript

James Shaheen: Hello, and welcome to Tricycle Talks. I’m James Shaheen, editor-in-chief of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Charles Johnson is a novelist, essayist, screenwriter, professor, philosopher, cartoonist, and martial arts teacher—and he’s also a Tricycle contributing editor. Over the course of his career, he has published ten novels, three cartoon collections, and a number of essay collections that explore Black life in America, often through the lens of Buddhist literature and philosophy. In the February issue of Tricycle, Johnson published a short story called “Is That So?,” which is a contemporary retelling of a classic Zen tale. In today’s episode of Tricycle Talks, I sit down with Chuck to discuss his path to writing, how Buddhism finds its way into his work, and why he believes that art should liberate us from calcified ways of thinking and seeing. James Shaheen: So I’m here with novelist Charles Johnson. Hi, Chuck. It’s great to be with you. Charles Johnson: It’s wonderful to talk to you again. James Shaheen: So Chuck, you’ve worked as a novelist, essayist, screenwriter, professor, philosopher, martial arts teacher, and Tricycle contributing editor. I remember I once asked you, Do you ever sleep? But before all of that, you started out as a political cartoonist. How did you get started in cartoons? Charles Johnson: I started publishing as a cartoonist when I was 17 years old. I could draw. When I was a kid in elementary school, it was my passion. And I came under the wing of a well-known cartoonist at the time, Lawrence Lariar, and took his two-year correspondence course. When I was 17, I started publishing. The first thing I published was a series of illustrations for a magic company in Chicago. But I was publishing in my high school newspaper as well. For seven intense years, I devoted myself to being a cartoonist and illustrator. A lot of my work was in the Black press at the time, publications like Jet Magazine and Black World and also the Chicago Tribune. I was an intern there for a while. It was a passion for seven years. And there’s a new book out now called All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End: The Cartoons of Charles Johnson. I just learned today that it was selected by NPR as one of the best books of 2022. So that was my early life. I majored in journalism as an undergraduate, which gave me a chance to draw and write. But it was in journalism that we had to take a required course in philosophy. And that was the beginning of a new passion for me. I was introduced to logical fallacies, which I’d heard all my life but didn’t have a name for, and also the philosophies of the pre-Socratics. I was seduced. So I decided after I was finished with my journalism degree, I would stay in school, get my master’s degree in philosophy and then ultimately my doctorate in philosophy. That’s Western philosophy. I focused on continental philosophy or phenomenology. But very early in my life, I was exposed to Eastern philosophy and Buddhism. I first practiced meditation when I was 14 years old. It was one of the most powerful experiences I’ve ever had. But I decided since I didn’t have a teacher, I would study Eastern philosophies. All the way through my undergraduate years, it would be my secret pleasure. But what happened is I ultimately had to get back to meditation—I’ve been meditating now for 42 years as of this year—find the right teachers and take my vows, which I did in the Soto Zen tradition in 2007. So Buddhism has been a part of my life since my earliest teens. James Shaheen: How did you come to Buddhism at age 14? Charles Johnson: Well, my mother was a great reader. She was in three book clubs. And she got a book on yoga. And I looked at it, and there was a chapter on meditation. I was a pretty smart kid, so I decided, “Let me try this for half an hour.” At 14, it was one of the most incredible experiences I’ve ever had. And when I got up from that thirty minutes, I discovered I had been living utterly in the present moment. I wasn’t thinking about the past or thinking about what I was going to do in the future. I felt compassion for my parents and for my friends. I felt extremely peaceful and in the present moment. So I spent a lot of time academically studying Eastern philosophy and then came back to meditation and the dharma. James Shaheen: So it was a year later at the ripe old age of 15 that they began to pay you to illustrate a magic catalog. Charles Johnson: 17. You can’t see it, but in my study here, I have one of the dollars from that first sale. And there were times when I was tempted to spend that dollar, but I didn’t. So yeah, my first sale was in 1965. James Shaheen: Wow. So later, when you heard Amiri Baraka give a talk in 1969, you were inspired to create a series of cartoons depicting Black life in America. Can you share more about how you view cartoons as a political tool and how this has shaped your work as a writer and artist more generally? Charles Johnson: I did every kind of comic art that you could imagine. The cartoons in the new cartoon book are single panel gag cartoons, but I worked as an editorial cartoonist for a newspaper when I was an undergraduate and for my college newspaper. Again, I was trained as a journalist. In literary circles, English department circles, they sometimes dismiss the visual arts because they don’t have the background or training in them. But comic art has an influence on popular culture that cannot be measured. We have had political cartoonists of note who had impacts on politics like Thomas Nast challenging Tammany Hall in the early 20th century. I’ve often said that a really well-drawn cartoon with a really good idea behind it can be experienced like a haiku. In a moment, it can give you a revelation. It can show you something that you have not seen or thought about concerning a situation, political or otherwise. James Shaheen: You mentioned twice All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End, which was quite popular and was covered in the mainstream press. What has it been like to look back at your earlier work? Has it given you any insight into how political art has changed over time? Because certainly it has. Charles Johnson: Well, when I look at the 250 cartoons in that book, I realize I don’t remember doing some of them. It was so long ago, over fifty years ago. Now, the book does cover early work and some recent cartooning that I did for Tricycle, some of the Zen cartoons and Buddhist cartoons. But some of the earlier work I looked at, I thought, “What was I thinking?” Now, back in the late ’60s and early ’70s, you have to realize it was more free-wheeling. In the early ’70s, you had comedians like Richard Pryor, you had shows like All in the Family, you had a lot of comedians who would just go for it. People didn’t feel offended. But as the decades have rolled along, I find today that people are extremely sensitive and wear their feelings on their sleeves. I think this is sad. James Shaheen: Do you feel the constraints yourself? Has it held you back at times when you wanted to do something but you thought people were going to respond and get very upset? Charles Johnson: Never. A good journalist does not believe in sacred cows. If a subject is worthy of exploring as a drawing, as a short story, as a novel, the artist has an obligation, I think, to go for it. James Shaheen: How did you go from being a cartoonist, among many other things, to writing novels? You’ve published ten works of fiction. They seem like two very different media, different ways to express yourself. How did this happen? Charles Johnson: All the arts are related. All of the arts are interconnected, just as we would say in Buddhism, everything is interconnected. I was a big reader. All the way through high school, I made myself read at least one book a week that had nothing to do with my schoolwork. And some weeks it became two, and some weeks it became three, because reading stories fed my imagination as a cartoonist. In the late ’60s, all my friends were involved in the arts in one way or another. I had friends who wanted to become the next Beatles and the next Rolling Stones. I had another friend who wrote six novels that never got published. We collaborated sometimes on comic strips for our college newspaper. So I was in an environment that was bubbling with creativity. So it happened one day that I had an idea for a novel. It was around 1970, I guess, and it wouldn’t let me sleep at night. I keep thinking of scenes. And so the only way to get rid of it was to sit down and write it, which I did over a summer. And it was written too quickly. But it was the beginning for me of novel writing. I wrote six novels in two years. With each novel I tried to improve. If in the first novel characterization was not working or plotting or description, in the next one, I tried to improve on those matters. After six novels in two years, I found myself coming into the orbit of novelist John Gardner, who was just on the rise at that time in 1972. He had published a critically acclaimed novel called Grendel, and his first bestseller was The Sunlight Dialogues in 1972. John took me under his wing. I knew nothing about the literary world. And I wrote the next book, the seventh book, which is my first published book, Faith and the Good Thing, in nine months with him looking over my shoulder. I thought that was an incredibly long period of time to do anything. Nine months working on something. I was talking to my friend, the editorial cartoonist, David Horsey, who is a two-time Pulitzer Prize–winning editorial cartoonist. He’s written a novel recently, but he said to me he was used to instant gratification. He’d do a drawing, and it’s in the newspaper the next day or two days later. With a novel, it’s a little bit different. So I spent nine months on my first published novel, Faith and the Good Thing, but after that, I began to realize what was at stake with every novel that I did. So the next book, Oxherding Tale, I spent five years on it. The next book, Middle Passage, which received the National Book Award, I spent six years on that and did a ton of research on the slave trade. And the book after that, Dreamer, I spent seven years studying Martin Luther King in every way that I possibly could, two years of research just before I wrote the first paragraph. James Shaheen: You write about Faith and the Good Thing that your aim was to enrich the tradition of African American philosophical fiction. Can you say more about the genre? Charles Johnson: Well, I’m working on a response right now to a magnificent book recently published by Richard Shusterman. The book is called Philosophy and the Art of Writing. It’s something I would recommend to everyone. It’s a seminal book. Those disciplines, philosophy and literature, have been united since the time, really, of the ancient Athenians. If you look at Plato’s Dialogues, they are dialogues. They occur in a dramatic form. If you look at Plato’s other dialogues, he has stories and anecdotes. In the West for the last 2000 years, you will find writers who understood instinctively that philosophy and literature were sister disciplines. Wordsworth as a poet understood that. Augustine understood that in the Confessions. T. S. Eliot truly understood it. We have a tradition of what is called philosophical fiction and philosophical poetry. But in America, I hate to say it, we have had currents of anti-intellectualism, so we don’t find that many people who have devoted themselves to the philosophical questions in our time. I think John Gardner was one of those people, especially with his novel Grendel, which is a kind of sendup of Sartrean existentialism. And also Saul Bellow. I like to think there’s philosophical dimensions of importance in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. And when I say philosophy and literature, I mean traditional philosophical questions that try to come to some degree of clarity but not a final solution, with questions of epistemology, political philosophy, ontology, the old traditional questions of philosophy. Every one of my novels has a core philosophical question at its center. In Faith and the Good Thing, the question is What is the good? That’s Plato’s old question. With Oxherding Tale, the question at the center of the novel is What is the self? In Middle Passage, the question is Where is home? And in Dreamer, the central question that kept me working on the book for seven years was How do we end social evil without creating new social evil? James Shaheen: So we recently had the writer Ben Okri on the podcast to discuss his latest novel, and he spoke about how art can help us face what we refuse to see. And in his case, he talks about the legacies of racism and oppression. I’m curious if this resonates with your own experience, especially since you’ve written so much about the histories of injustice in the United States. Charles Johnson: Yes, it does resonate. My position has always been that the goal of art should be the liberation of our perception. It should liberate us from calcified ways of seeing and even being. There’s a Rilke poem that I have always loved since I was a teenager and first read it, in which a viewer is looking at a Greek statue, and it’s partly shattered. It isn’t completely there, but it’s beautiful. And the last line of the poem is the viewer thinking, “I must change my life.” That’s what art should do to us. A reader, a viewer, should not come out of a work of art as clean as they went into it. Same thing for the writer. For me, every novel I write as if it’s the last thing I’m ever going to do. I’m willing to spend five years, six years, seven years on that novel if necessary as a way of trying to clarify things for myself and I hope for a reader as well. Now, sometimes, I’ve had assignments where I had to write about what you’re talking about, race, which is not always an easy thing to write about. There are easy ways that people think about race. I’m more interested in the deeper ways that we can think about this particular subject. My position has always been that race is an illusion. But it is a lived illusion that has caused enormous damage for the longest time in human history. When I write about race, I’m always trying to probe deeper into whatever the subject is because it touches upon things like identity, personal identity, things that Buddhists have for 2,600 years been wrestling with, talking about, helping us understand better. James Shaheen: Your novels tend to infuse stories of Black life in America with Buddhist folktales and parables, and you mentioned Oxherding Tale, one of your books, and it follows an enslaved man’s journey to freedom through the lens of the ten Zen oxherding pictures. Can you say more about how you bring Buddhist themes into your work? You’ve said that your mentor, John Gardner, initially disapproved of your interest in Buddhism. So I’m very curious to hear about that. Why was that? And how did you decide to stick with Buddhism anyway? Because it runs through your books. Charles Johnson: Well, John was good to work with for my first novel, Faith and the Good Thing. My next novel, Oxherding Tale, not so good. He was a shyly Christian writer. I couldn’t figure out why he was resisting this book, although other people resisted it too. But he said to me, “If Buddhism is right, then I’ve lived my life wrong. And I refuse to accept that.” What I realized at that point was that as a teacher, he had been very good with turning me in a certain direction for craft. But when it came to my vision, which was different from his, we had to go separate ways. That book, Oxherding Tale, was rejected as many times as Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Nobody understood that book in 1980. It was published first by Indiana University Press. That led to a review by the late culture critic Stanley Crouch. He wrote a two-page review in The Village Voice, and that cemented the book for readers in the sense that Grove Press picked it up and kept it out there. And then one thing leads to another. That book led me to do Middle Passage and receive the National Book Award. James Shaheen: So throughout all of this and throughout your career, you’ve been meditating. I was wondering what the relationship is between your meditation practice and your writing. Do you view the writing, say, as a spiritual practice or as a meditative practice? Charles Johnson: Whatever creative work I’m doing is an extension of my spiritual life. My work is informed by it. But I have to say that after so many years of meditation, I see everything as part of my spiritual practice. Whether I’m engaging with my grandson or whether I’m going to the supermarket and talking to the person checking out my groceries, I try to be in that place of spiritual consciousness all the time. Now, just before we started, I sat on my tattered and worn zafu and had my formal sit because I would not do a session like this until I cleared my head and spirit. The point is that when I get up off my pillow, I want to have that same consciousness throughout the day. It’s about everything that I do. That includes creative work as well. James Shaheen: You always have struck me as an incredibly disciplined man in just about everything you do in the many fields you work in. There’s a real Protestant work ethic going there, too. It’s pretty amazing to watch. But I remember once I was listening to Michael Imperioli and Philip Glass and Gelek Rinpoche on a panel, and both Philip and Michael were saying that the very thing that made them disciplined and able to apply themselves to their work the way they did was what also allowed them to apply themselves to their practice and explore in a similar way. Is that true for you? Charles Johnson: We’re talking about a particular kind of discipline, I suppose. And it does bleed over into every aspect of our lives. The beauty of Buddhist practice is that it allows us to bring a degree of control over our lives. We learn how to look at our own mind and the arising and falling of thoughts and feelings and to be able, with equanimity, to examine those thoughts and feelings and not be caught up in anger, for example. It is very much a part of my discipline. James Shaheen: So as if you don’t do enough, for the past few decades, you’ve studied Sanskrit intensively. Sarah, our producer, tipped me off to a blog post you wrote for Ethelbert Miller, and you describe it as your “most serious intellectual and spiritual hobby, a language I will study until the last day of my life.” That’s commitment. Can you say more about how you came to study Sanskrit and what you love about it? Charles Johnson: Well, when I was in my teens and I was doing my Eastern philosophy studies, I naturally came across Sanskrit. And I always thought I didn’t have any talent for languages. Middle school, high school, all the way through college, I think I had seven years of Spanish, but I don’t have a natural talent because I think I’m a visual person. Some people are ear people. They hear with subtlety. I don’t. And that’s what you really need to know three or four different languages. But as it turned out, one day, we were working out in our martial art studio. On the bulletin board, they had put up a little flier. So when we were taking a break from working out, I looked at it, and it said, “Learn Sanskrit over the weekend.” It was a flier for the American Sanskrit Institute. And their approach is rather different from academic foreign language Sanskrit departments. And so I went, and it was a wonderful, incredible three days of immersion with my teacher Aja Thomas, who is a priest actually. And so I’ve started with Aja for a long, long time. The American Sanskrit Institute approach is holistic, the same way it was in India and is in India. It is my most serious intellectual hobby. I wish I had time to get back to it because I really have to study every day to make progress. I’m writing a piece right now on this book, Philosophy and the Art of Writing, that’s taking up all my time. But I walk around with Sanskrit in my head all the time. James Shaheen: Has it in any way shaped how you write in English or changed the way you write in English? Do you play with that? Charles Johnson: Oh, absolutely. When I first started studying Sanskrit, I would be grading my students’ papers, their stories, and so forth. My sensitivity to language was so acute in terms of rhythm and measure. It really had a good impact on dealing with my students’ work but also my own work, too. James Shaheen: I mentioned you’re a Sanskritist and a cartoonist. You’re also a martial arts teacher. And I wonder what drew you to the martial arts? And do you see a relationship between your martial arts practice and your writing? Charles Johnson: I started martial arts when I was 19 in Chicago at Chi Tao Chuan of the Monastery. It was like a cult really. I did a lot of karate, and I finally settled in the early 80s into one system, Choy Li Fut, as taught by Grandmaster Doc-Fai Wong in San Francisco. I started there, training in his school. Then we had schools here in Seattle in Bremerton, Washington. So I’ve been doing this for a long, long time. We have a workout tonight, as a matter of fact, with me and some of my old friends. I’m 70. The other guy is 50. We have seen some of our teachers and friends pass on over this long period of time that we’ve been training, but we still get back to it. Because one of the things you want to do in life, if possible, is the integration of mind, body, and spirit. I think I said to you before in our last interview, when I was young, I said, “That’s what I want to do. I’m going to develop myself in three directions: mind, body, and spirit.” For mind, I chose philosophy. For body, I chose the martial arts. And for spirit, I chose Buddhism. They flow together and reinforce each other in one way or another. I will have to say that there are certain very high kicks I don’t want to do anymore. I have to be very careful about it at age 74, or I’m going to feel it the next day. So you make adjustments over time. Tai chi is very important to me right now. James Shaheen: You recently published a graphic novel called Eightfold Path, aptly enough, which is an anthology of Afrofuturistic parables inspired by the Buddha’s teachings. Can you tell us a little bit about the project and how it came about? Charles Johnson: It was a collaborative work. I went along for the ride. That’s the way I see it. The stories are by my friend, the Afrofuturist sci-fi writer Steven Barnes, who has published a lot of books, and it was illustrated by Bryan Moss, a talented young artist. And what Steve wanted to do was a graphic novel. He was inspired by the old EC horror stories, but he didn’t really have a background in Buddhism. So he brought me on board to interject in places where I could both Western philosophy but also as much Buddhism as I could get into his stories. And then I wrote a final essay that’s at the end of the book explaining for readers what the eightfold path is if they don’t know. James Shaheen: We recently interviewed Bernard Faure on the podcast, the historian of religion, and he celebrates the multiple manifestations of the Buddha from the early texts to graphic novels to science fiction. He spoke about how cultures have continually reinvented the story of the Buddha, constructing new myths and developing new genres. It seems like this graphic novel anthology is a continuation of that tradition. What can be gained by translating Buddhist teachings and stories into other mediums? Charles Johnson: Buddhism is 2,600 years old, and nothing was written down in terms of my understanding for about 500 years. So it was an oral tradition. So there were technologies that developed over millennia for the communication of dharma that didn’t exist in the Buddha’s time and didn’t exist in the 19th century. A new form that is very popular in this country right now is the graphic novel, graphic arts. The impact graphic novels have had on popular culture to me is amazing: on movies, on television programs. They are the source material. So why not for introducing readers to the dharma? James Shaheen: Do you like depictions of the Buddha in manga? Charles Johnson: It’s OK. It’s very influential. I’ve got comics here in my garage, and among them, you’re going to find manga. I have a series that was done on the life of the Buddha in a manga form. Yeah, it’s absolutely OK. James Shaheen: I imagine we’ll continue to create new Buddhas and new forms as long as we’re around. In the February issue, your retelling of an old Zen tale appears. The story is called “Is That So?” What can you tell us about that story and what it means to you? Charles Johnson: I thank you for taking that story and publishing it. Since my teens, that was when I first encountered that story, which is only three paragraphs in a lot of the versions that I’ve seen, I’ve simply thought about it for all of my life. In 1998, I fathered a reading series here in Seattle for Humanities Washington. It used to be called the Washington Commission for the Humanities. Every year, they have a fundraiser in October, and I suggested, why not have writers write a new story and read it, and you give us a theme or a prompt. Every year, there’s a different theme related to bedtime. The one for the story you’re talking about was light in the darkness. And many writers locally have participated in the bedtime stories event. My late friend, the playwright August Wilson, did it three times. My former student, David Guterson, author of Snow Falling on Cedars, has done it. So I had to write a bedtime story. And my thought was, “What do I want to write about light in the darkness?” And so I reached back to that story. I thought to myself: Suppose I update it. Suppose I set it on Vashon Island. I said, Well, let’s look specifically. What would happen if you suddenly had a baby put in front of you, and you had to take care of it? What I thought about in terms of the details was this will become for this abbot his way, his practice, this baby, which, in order to take care of a child, you have to stop being a child yourself. So every moment of the day, this life is one he’s responsible for. It transforms him. People think it’s his baby. And so his temple begins to lose parishioners and laypeople. But he stays the course until the grandparents come and ask for the baby back because their daughter had lied to them about him being the father. So now he has to experience letting go. First, the process of dealing with this baby, which creates him as a father and a mother through love and identification with this child, and then the child is taken away. So he has to learn at the end of the story how to have a deeper and more fully realized broken heart. James Shaheen: As I remember, the first time I read it, it had more to do in my mind with this is your child, he says, “Is that so,” he accepts it with a complaint, and then they come to take it and they say, “This isn’t your child,” he says, “Is that so,” and they take it. I thought of it in terms of praise and blame, but in this story, it’s really about unexpected gain and then a terrible loss. Charles Johnson: Yeah, it’s a powerful story about accepting the present moment. Oh, is that so? OK. But I kept thinking to myself, “What changes is this abbot going through as he takes care of this baby, and what emotional changes?” His life is turned upside down, but he has learned from the experience and evolved spiritually. But it doesn’t come without pain and suffering. James Shaheen: Well, I was abroad, and I was lying in bed when your agents sent it to me, and I thought, “Oh, this is a novel,” and I put it aside for a moment and wrote her back and said I would read this book when I get back to the United States. She wrote back and said, “It’s not a book.” So I read it really quickly, and I was immediately smitten, and I thought, “OK, we’ve got to publish this.” So thank you for that. For our readers, you can read it in the February issue. It’s a wonderful retelling of an old Zen tale. So Chuck, between Sanskrit study, martial arts, and your many, many publications, it seems like you always got an iron in the fire. So what are you working on now? Charles Johnson: I’m working on trying not to be working on things. Yeah, I’m always working on something because I’m always curious about the world and what’s going on. I don’t force it. And when there’s a story to write or a drawing to do, then I do it. James Shaheen: Well, Charles Johnson, it’s been a great pleasure. For our listeners, be sure to check out Chuck’s story in the February issue of Tricycle and his many, many books. Just go online, google Charles Johnson, and you’ll find a very long, I would say endless, list of work. It’s always a pleasure to talk to you. So thank you, Chuck. Charles Johnson: Thank you. James Shaheen: You’ve been listening to Tricycle Talks with Charles Johnson. To read his story in the February issue of Tricycle, visit tricycle.org/magazine. Others featured in the issue include Karen Armstrong, Pico Iyer, and Jacqueline Stone, along with teachings on how stories and myths shape our understanding of ourselves and the world. We’d love to hear your thoughts about the podcast, so write us at feedback@tricycle.org to let us know what you think. If you enjoyed this episode, please consider leaving a review on Apple Podcasts. To keep up with the show, you can follow Tricycle Talks wherever you listen to podcasts. Tricycle Talks is produced by As It Should Be Productions and Sarah Fleming. I’m James Shaheen, editor-in-chief of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Thanks for listening!

Sponsored by St. John’s College

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.