Nepal entered a nationwide lockdown on March 24, closing its borders and suspending international flights. Set to expire after a week, the lockdown remained in place, ending last week on July 21. Although the number of COVID-19 cases in Nepal remains low, even a minor outbreak would swiftly overwhelm the small country’s already strained healthcare infrastructure.

In Kathmandu, usually awash in noise and heavy with smog, the streets were mostly empty and the air was clean. Temple courtyards, typically packed in the early mornings, were abandoned for months. In a city where religious practice is a major component of life, most worshipers have found themselves unable to participate in group rituals. But one group—the Newar Buddhists—have found new ways to continue their centuries-old practice.

Newars are the indigenous people of the Kathmandu Valley. Although Newar Buddhism has received comparatively little attention in the global Buddhist community, the importance of Newar Buddhists cannot be overstated. It was in their libraries that the Sanskrit originals of texts such as the Perfection of Wisdom sutras were preserved. This is because Newar Buddhists practice the only extant form of the Vajrayana tradition in which all liturgical material is in Sanskrit. Theirs is also the only form of the religion with specifically Buddhist hereditary roles, typically called “castes” and loosely divided along priestly (the Vajracharyas and Shakyas) and mercantile lines, such as the Uray. (There are also broader Newar castes, such as Shreshthas and Maharjans, that elude categorization as either “Buddhist” or “Hindu,” with members making offerings to deities from both religions.)

Vajracharyas, most notably, perform rituals in urban public spaces, often involving a few participants, or even, on occasion, hundreds of people. These rituals, scheduled around the lunar calendar, are a crucial component of the religious life of practicing Newar Buddhists. Along with Shakyas and Urays, Vajracharyas also perform the role of teaching the dharma to the local community.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made these traditional ways of teaching and performing rituals impossible. But rather than remain idle in their homes, Newar Buddhists shifted their ritual and teaching centers online the moment the lockdown began.

One particular Vajracharya leader, Yagyaman Pati Bajracharya, spearheaded the online initiative. At almost 80, Yagyaman Pati is not your stereotypical picture of a social media influencer, yet he realized the power and reach of the Internet years ago, regularly using Facebook as an outreach and organizational tool. When the lockdown went into effect, it was easy for him to move his operation online. Now, using Zoom, Yagyaman Pati teaches dharma, maintains the Buddhist organizations he heads, and instructs teachers of tantric song and dance (caryagiti) on performances they should undertake, which are then promoted through Facebook.

Prior to the lockdown, he hosted weekly teachings open to anyone at Kathmandu’s Jamal and Shikamu bahahs (temples) through his organization Bauddha Darshan Adhyayan Puchaa, or Buddhism Study Group. The teachings were held in temples, often in a packed upstairs room. During the lockdown, teachings previously given weekly were often given daily online, and with no geographic limitations, Newars from as far away as Canada and Australia joined in.

Yagyman Pati is not alone in bringing teachings into a digital space. Several other Nepalese dharma teachers and organizations are also using technology to reach students. Public intellectual Abhilash Acharya regularly uploads teaching videos to Facebook, in Nepali or English, and the Newar Buddhist teaching organization Guita Buddha Sikshya Jagaran hosts weekly Zoom dharma discussions in Newar. A number of non-Buddhist Newar groups, usually Newar language preservation groups or Hindu groups, connect regularly through Zoom, and post meeting notes on their Facebook feeds. These free online teachings, open to anyone with an internet connection, have eliminated many of the barriers practitioners may have encountered in a temple before COVID-19.

Newar Buddhists are also using social media to help combat the coronavirus itself. Yagyaman Pati has instructed his core students through both Zoom and direct messages on Facebook to use particular rituals and mantra recitations to help slow the spread of the virus. Students are uploading to Facebook videos of themselves performing tantric dance and reciting mantras—all with the understanding that their collective efforts are spiritual contributions in the fight against the virus.

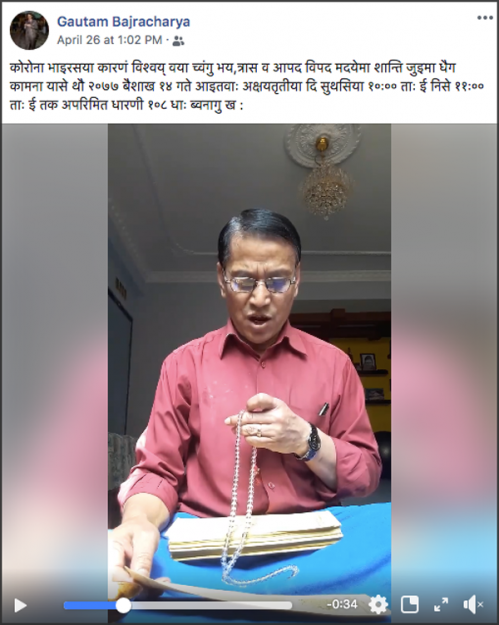

Along with teachings and practice, Newars are using virtual spaces to combat the pandemic with apotropaic rituals. Vajracharya priest Gautam Bajracharya posted a video of himself on Facebook reciting Sanskrit mantras that invoke the buddhas, petitioning them to grant unlimited merit to all beings. Another Vajracharya, Rajesh Gurju, uploaded a video of himself reciting a series of empowering mantras meant to stop the virus. Alongside it, he posted a video of himself performing a tantric dance.The two videos, playing simultaneously and side by side, are intended to generate more power. In addition to recitations, Rajesh posted photos of himself meditating and performing postural yoga, and even uploaded an old image of himself when he was a monk. All of these efforts are meant to end the pandemic. Joining the battle against the virus, many Newar Buddhists fill their Facebook feeds with daily written mantras (such as om tare tuttare ture svaha), with the Nepali date.

A number of Yagyaman Pati’s female followers have also posted videos of their daughters doing their part to help slow the virus. Rina Maharjan, a teacher of tantric dance and student of Yagyaman Pati, regularly posts pictures of her daughter Agria keeping herself occupied during the quarantine. When not drawing or gardening on the rooftop, Agria constructs dharmadhatu mandalas from lime powder and recites mantras to alleviate the pandemic. A number of others have posted videos of their young daughters making the same mandala and reciting the same mantras. Teenage girls who are students of tantric dance have uploaded videos side by side, dancing in sync.

Buddha Jayanti, the Buddha’s birthday, which fell on May 7 this year, is typically one of the famously colorful Newar festivals. Stuck inside, Buddhists in Nepal honored Shakyamuni in the digital space. On Buddha Jayanti, dazzling images of the Buddha bedecked Facebook feeds in a way reminiscent of the brilliant garb worn by the Buddha himself.

The adaptations have not been entirely online. At the famed Svayambhu Stupa (often called “the monkey temple” in Nepal guide books), the hereditary priest Amrit Man Buddhacharya made the daily offerings of rice he and his Shakya relatives would accept from local pilgrims in normal times.

“The master [Yagyman Pati] ordered me to give rice at the places around the mandala and Ajima [the goddess]. I did it every morning for three months,” Amrit explained. Ajima “is believed to protect the people from diseases, so we pray to her for this type of thing.” Amrit noted that Yagyaman Pati informed him that although each rice offering “looks a small thing, when you give it to the Buddha it helps to go all around the world in this hard time. This way people all around the world can get food and health since in lockdown people may not be able to get food and work.”

Newar Buddhists have a reputation for being wary of outsiders, which includes foreigners and those without proper birthright. Exclusion based on caste and gender has led many to view the traditional Buddhism of Nepal as closed-off. But Newar Buddhism is a dynamic tradition all its own, and in the last decade local leaders have responded to a changing world by shifting into a more welcoming attitude. The response of Newar Buddhists to the pandemic and the lockdown has brought this striking adaptability to the surface.

When the lockdown began to ease in late June, Newar Buddhists slowly began returning to their religious sites. Despite the possibility of performing rituals in a traditional setting once again, the efficacy of teaching and practicing in a digital space is now undeniable. As familiar ways of practice become possible again, it seems likely that new practices will find their place in this evolving tradition.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.