The arc of Pema Rinzin’s journey as an artist is apparent as soon as I enter the New York Tibetan Art Studio (NYTAS), his workspace and residence in Brooklyn. The walls are filled with thangka paintings, ornate renderings of Tibetan Buddhist deities and historical figures. Some of the thangkas are reproductions of classic paintings dating back hundreds of years; others are Rinzin’s own creations. Thangkas—from Thang Ka (“recorded message that can be rolled”)—were originally scrolls used by traveling lamas to teach the sutras. But Rinzin, at 52, has given the centuries-old form a 21st-century incarnation.

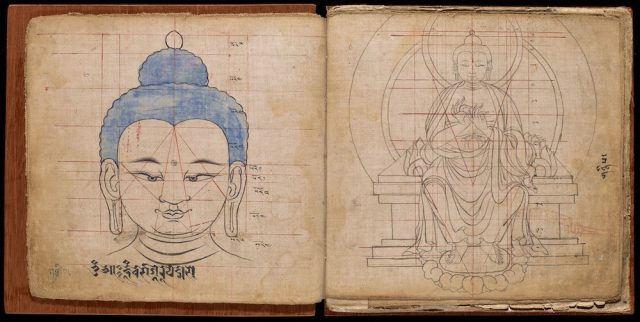

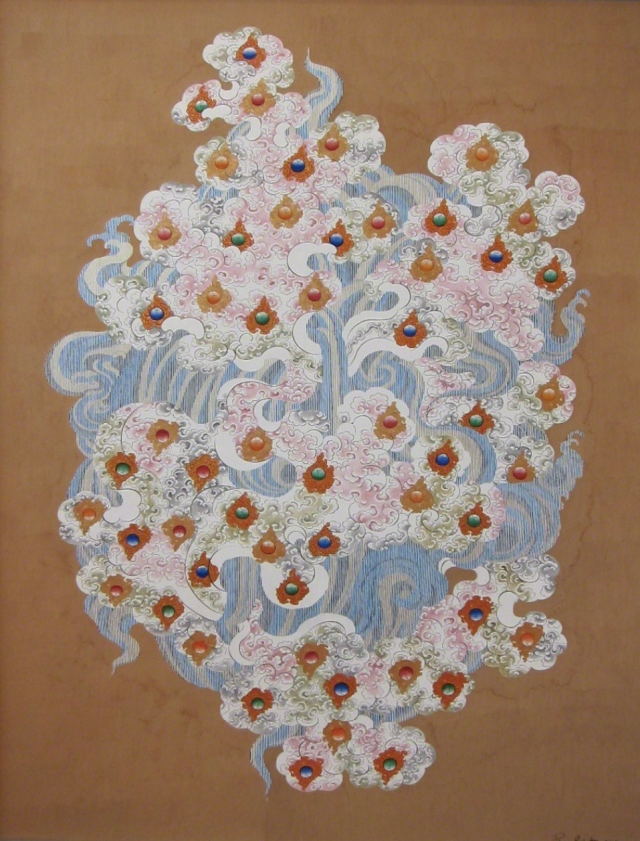

While two of his students sit at easels, carefully sketching drawings of the Buddha and the female deity Green Tara on precisely measured grids, Rinzin is filling a large canvas with perfect white circles, painted freehand, on a deep blue background. The “bubbles,” he explains, are “wish-fulfilling gems,” an often unnoticed but ubiquitous element in thangka paintings.

Rinzin’s own wish is to inspire viewers to see thangkas not merely as illustrations of Buddhist teachings but as examples of astonishing artistry made by masters, who have all too often remained unknown in the West. But for Rinzin, this has meant departing radically from the traditional thangka style. Iconographic Buddhist figures have been stripped away to reveal what Rinzin sees as the fundamental elements of Tibetan art: its rich colors and the grace and flow of individually painted leaves, birds, fish, and “bubbles.”

Related: Tantric Art: Then And Now

Rinzin was born in the mountains of Nepal in 1966, after his parents had fled Chinese-occupied Tibet. He grew up in Dharamsala, India, the seat of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government in-exile. As a precocious 13-year-old with a gift for drawing, Rinzin was allowed to study thangka painting at the Tibetan Children’s Village (TCV), a crowded youth hostel directed by the Dalai Lama’s sisters, the late Tsering Dolma and Jetsun Pema. In 2005, he moved to New York and spent three years as artist-in-residence at the Rubin Museum of Art before founding the NYTAS. Rinzin’s artistic career is flourishing in the vibrant New York contemporary art world, where his paintings sell for as much as $100,000.

Recently, while his students worked in the adjoining room, Rinzin and I spent an afternoon in the sunlit kitchen of the NYTAS discussing his journey from life as a refugee to that of a sought-after artist breathing new life into Tibetan art.

Was it clear from the start that you were artistically gifted?

If you’re an artist, you’re a born artist—there’s no way to escape that. But without resources or exposure to art, it’s very difficult. There were no museums or art galleries in Dharamsala and hardly any art books or supplies at the school. Each student had one notebook and one pencil that were supposed to last you the whole term. Your pencil was marked with your student number, and the teacher collected it after class.

How did you start to draw?

We all studied English in grade school, and I made an alphabet chart for the class, showing A for apple, B for boy, like that. In science class, I made a chart of the water cycle. My teachers liked what I did and gave me little treats to eat. We were always hungry, so I felt very lucky. I learned that if you were good at art, you might get rewarded.

Related: Dancing with the Divine Feminine

What attracted you to thangkas?

That was the only art class you could take at TCV. What I really liked was that the art students didn’t have to take other classes. I was bored with regular schoolwork, and it seemed like all they had to do was make art, walk in the forest, and play basketball. That’s what I wanted to do.

Was studying thangka painting really so free and easy?

Not at all. When you study Tibetan painting, you do it full-time. You draw all day long, always the same three figures—Buddha, the wrathful deity Vajrapani, and Green Tara. It takes a long time to be any good, and after a few years, I began to get bored with that, too, and was more interested in Western art.

How did you learn about Western art?

Everything I knew came from secondhand Newsweek and National Geographic magazines that I’d read at school. Sometimes there would be stories about modern artists like Picasso and Salvador Dali selling their paintings for millions of dollars. When you’re as poor as I was, that’s inspiring.

Did you like Dali’s and Picasso’s paintings?

I understand cubism and surrealism now, but back then it was very difficult for me. It would be difficult for any Tibetan. Tibetan art is figurative. Most Tibetans, if they found a Picasso on the street, would throw it in the garbage.

What other kinds of Western art influenced you?

I liked cartoons. We didn’t have books about fine art, but we did have comic books—Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, Tom and Jerry. Those were my favorites. I liked drawing cartoons because you can do so many different facial expressions. I was quite good at it.

So, when you were in your twenties, you were no longer doing Tibetan art.

No, I stopped doing that completely. I was only interested in Western art.

You took a trip to New York in 1989 to learn more about Western art. But when you saw that Tibetan art was completely absent from Western museums, that changed things for you.

At that point, I saw that the world didn’t need a Tibetan artist to make Western art. It needed a Tibetan artist to bring Tibetan art to the West.

So you returned to Dharamsala, where you studied thangka painting for 10 years. Was studying Tibetan art in your thirties the same or different from when you were a teenager?

It was different because I was more mature and more self-disciplined. But it was the same routine. You sit your ass down and draw and draw and draw Buddha, Vajrapani, and Green Tara over and over again. You become like a machine, until you can do it exactly like the teacher. That takes years, but it’s just the beginning.

Being able to draw as perfectly as the teacher is just the beginning?

Making thangkas is not just about drawing and painting precisely. It’s about personal expression and emotion, like all great art.

But aren’t the images in thangka paintings drawn on grids with very precise measurements? It seems like the goal is to take the artist’s ego and emotion out of it.

Not at all. You need a lot of ego, a lot of passion, if you’re going to be any good. The gridlines and measurements are just tools, like rulers or brushes. They’re helpful, but they won’t make you a good artist. You can know everything about the correct measurements of the Buddha’s eyebrow and not be able to draw one leaf properly. To be skillful enough to get one leaf to flow freely from your mind to your hand takes years of dedication.

So to appreciate the true artistry of a thangka you have to look at the details.

It’s not just the details. To fully appreciate Tibetan art, you have to look beyond the surface, at the draftsmanship, the use of color, the individual style of the artist. This is something many Westerners miss. They know about the Buddha and the religious figures in the painting, but nothing about the artist who made the painting, not even his name. Can you imagine someone looking at a religious painting by da Vinci and talking only about Jesus, without even knowing da Vinci’s name?

One of your teachers was Kalsang Lodroe Oshoe, who is the court painter to the Dalai Lama. What was he like?

He was young, only about 10 years older than me. He’s from a line of master artists. He’d grown up in Bhutan, where his father was the royal painter to the king. Kelsang is amazing. Watching him draw was like watching Michelangelo—the perfection of his composition, his understanding of color . . . and his speed! He was like this with the charcoal: zoom, zoom, zoom. Then the color, the shading—all high speed.

But learning is slow.

Learning is very slow.

You say Tibetan artists are unknown in the West. How are they regarded in the Tibetan community?

Artists are highly respected. If you’re good, you’re treated like royalty.

Do you have to be a devout Buddhist to be a master thangka painter?

Some are more devout than others. Kalsang Oshoe was very devout and had a complicated daily practice of offerings and prayers. But you can be a great painter without taking a vow.

Do you meditate?

My work is my meditation. It’s a natural meditation. You can close your eyes and sit quietly and meditate, but that won’t help you paint. You have to use your hand, your mind, your body. You can’t separate it from your work.

If Tibetan artists are to gain greater recognition, what needs to change?

People can start by using the names of the artists who make the paintings, the masters like my teachers Rigdzin Paljor, Kalsang Oshoe, and Khepa Gonpo. But it’s especially important for the next generation of Tibetan artists. In the future, when you see a Tibetan painting, you should know who made it and not just think of it as a religious object, so the artist isn’t left out.

Is that why you started painting in a contemporary style?

I saw no other future. I wasn’t being recognized for my traditional work, and at the same time I was getting a lot of energy from the New York art scene. But I didn’t change what I was doing only because I wanted recognition. It was also a way to get people to look at Tibetan art and appreciate it, a way to keep it alive.

When you started doing your contemporary paintings, did people respond positively?

Many of my students didn’t understand. They said, “Pema, why are you doing this?” But I feel like if you really know Tibetan art you can do anything. You’re a true master, a master of color, of composition, and self-expression. When you know the form, you can break it into a hundred pieces, and they will still shine like wish-fulfilling gems.

Pema Rinzin is represented by Joshua Liner Gallery.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.