David Ulrich noticed the connection between meditation and the power of images during his first college photography class in 1971.

That day, he recalled, “we noisily entered the room to observe the teacher seated in a lotus position in the front of it.” “He began the class with the statement ‘It is my belief that creativity arises from stillness.’ In that class, meditation was the gateway to seeing.”

Ulrich’s new book, Zen Camera: Creative Awakening With a Daily Practice in Photography, is intended as a guide for others—professionals or not—to create mindful images that reveal the photographer’s inner philosophy.

“I think that one of the most important things asked of us by Buddhism is to learn simply to see what is as we look both inward and outward,” Ulrich told Tricycle. “If you take time with the subject and use the camera as a way of interacting with the world rather than mindlessly taking pictures and selfies, the camera can teach you about your own authentic way of seeing.”

Related: PHOTOS: The Natural Artwork of Japan’s Buddhist Temple Walls

Ulrich knows firsthand how developing a mindful approach to photography can be transformative.“I lost my eye chopping wood in the early 1990s. I spent two years learning to see again,” Ulrich shared. “The injury had an effect similar to the Zen master’s stick and ironically widened my perspective.”

It was during his recovery that Ulrich began feeling an urge to travel to Hawaii while working to resume his career in photography. He eventually moved from his then-home in Massachusetts to the Aloha State, where he still lives.

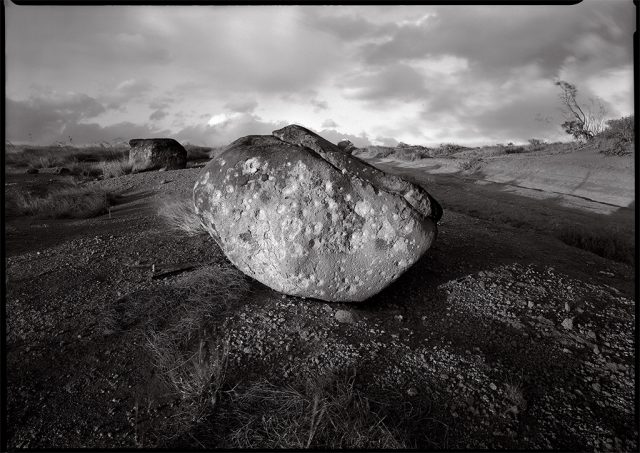

“My own photographic work often takes the form of long-term projects dealing with the cultural landscape of Hawaii and other places,” he said. “In one major project, I was commissioned along with two other photographers to document the island of Kahoolawe,” a Hawaiian island that was commandeered by the U.S. Army after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. “The place was like nothing else I have ever experienced. The contrast between the deep sacredness of the land and the terrifying damage caused by modern weaponry was haunting.”

“In order to photograph this,” Ulrich remarked, “we had to attempt to move beyond our ego’s desire to make good photographs, and simply try to listen and see, to stay in the moment and allow the island to speak through our lenses.”

But Ulrich stressed that it does not take a life-altering event to change the way you approach photography—especially since we live in an era where everyone has a camera in their pocket. He offered these tips for Tricycle readers looking to change the way they view their surroundings.

Use the TMP method. “What I recommend to students is what I call TMP—take more pictures. Keep your mind open and explore the world with a sense of ‘not-knowing.’ One of the things I find is that many professional photographers have a Zen attitude,” Ulrich explained. “They don’t know. They explore and stay open and attentive. They don’t know what they will find. They strive to move beyond their preconceptions and approach the world as a question and thus keep its mystery intact.”

A professional photographer, Ulrich continued, takes hundreds of photos in order to obtain the perfect shot. “But an amateur photographer takes two or three and then walks away, instead of working with attention and staying in touch with the process of discovery,” said Ulrich. “The camera helps us see, but we need to work with the subject.”

To do this, Ulrich suggests that beginning photographers experiment with zooming in and out on their camera phones and try new angles and close-ups.

Ask how you’d define your own artistic vision. As a photography instructor for over 40 years, Ulrich has seen his students develop their own style over time. “It really comes down to the question of ‘Where do you find resonance?’” he explained. “What you seek is a deep sense of resonance with what is unique for each person. People have their own core interests and strengths, and need to uncover their own natural wisdom and inherent vision.”

“For some of my students it’s an attention to color or form, while others explore their own identity through a camera. Others have a great capacity for compassion and explore that through portraiture,” said Ulrich. “It runs the gamut, but each person has a particular way of seeing that infuses their work with authenticity and a personal style.”

Redefine your relationship to your smartphone. While we all know how distracting and addictive our cell phones are, Ulrich says that we should not completely write off how they can be used as tools for good, particularly when it comes to mindfulness. “That’s the very question Buddhism asks. ‘How can we go from distraction to being located in the present moment?’” Ulrich observed. “The camera is a discipline that can foster mindful awareness, with part of our attention going out to the world and part of our attention remaining inward to observe how our senses, feelings, and mind respond to the world.”

Though parents in particular understandably worry about kids and teens who constantly take selfies and Snapchats, Ulrich noted that it is possible to redirect a child’s energy into creating something meaningful.

“I work with students who are as young as 10 or 11 to people who are senior citizens. Photography is one of the dominant mediums of the 21st century,” Ulrich said. “The camera can be an enjoyable way of learning about your own nature.”

Related: PHOTOS: Tibetan Buddhist Nuns in the Himalayas

But there are also times where just putting away your phone is appropriate.

“Sometimes, we need to create acts of resistance—to resist the draw of the device, to put it aside for a period of time, and to consciously experience this discomfort,” he said. “By resisting the draw of our devices, we can generate attention and force for enhancing our awareness.”

In the end, said Ulrich, homing in on your natural responses to the world is the key to discovering themes that strike a chord in your art. “With mindful attention, you can observe your inner response to what you see and discover your points of resonance with the world,” he said.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.