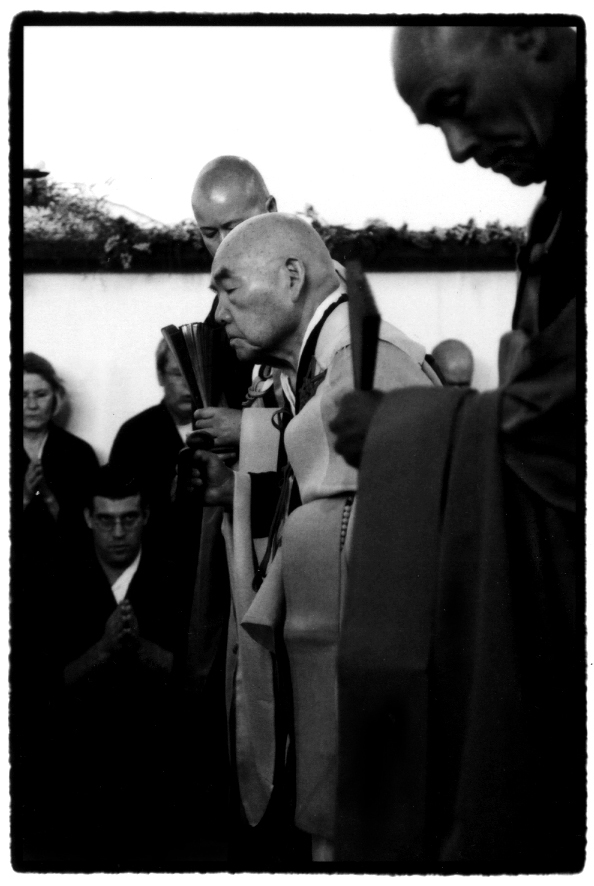

On Sunday, Joshu Sasaki Roshi, a Rinzai Zen Buddhist who came to the United States in 1962 and went on to become one of the country’s most influential, if not most controversial, Zen teachers, died at Cedars-Sinai medical center in Los Angeles. He was 107 years old.

Although said to have no dharma heirs, Joshu Roshi had legions of followers who founded about 30 Zen centers, from Seattle to Oslo, Vancouver to Berlin, some of which later closed. He led a large center in Los Angeles and two training centers in the Southwest, one in New Mexico and one at Mount Baldy, in the mountains east of Los Angeles. The poet and songwriter Leonard Cohen lived at Mount Baldy in the 1990s, lending his teacher a semimythic status among spiritually inclined rock fans.

It’s safe to say that nobody in the last century has, directly or indirectly, led more people to Rinzai Zen teachings than this ancient teacher, born in imperial Japan and made a roshi when the memory of Hiroshima was but two years in the past.

Yet if Joshu Roshi was extraordinary in his reach, he was depressingly common in what we might call his grasp. As I reported in The New York Times last year—outing what had long been common knowledge in the Zen Buddhist world—Joshu Roshi had for decades groped and harassed female students, often quite violently. Although the board of one center received letters about his conduct as early as 1991, it was not until one of his former monks, Eshu Martin, posted an open letter on SweepingZen.com in 2012, that the board took action.

An independent “witnessing council” of Zen teachers also initiated an investigation, publishing a report last year that described incidents like “Sasaki asking women to show him their breasts, as part of ‘answering’ a koan”— a Zen riddle—“or to demonstrate ‘non-attachment.’” When women reported sexually assaultive behavior, they found the male monks unsympathetic. And when I reported on this story last year, after Joshu Roshi had largely retired from active teaching, a reservoir of sympathy for the man still remained.

Bob Mammoser, a resident monk at Rinzai-ji, told me that he had been aware of allegations against Joshu Roshi since the 1980s. And he didn’t seem to doubt them. “What’s important and is overlooked,” he told me, “is that, besides this aspect, Roshi was a commanding and inspiring figure using Buddhist practice to help thousands find more peace, clarity, and happiness in their own lives.” He said that with teachers “you get the person as a whole, good and bad, just like you marry somebody and you get their strengths and wonderful qualities as well as their weaknesses.”

Joshu Roshi’s behavior was all too typical of the early generation of Japanese teachers in America, who arrived just in time for the explosion of interest in Eastern religion. They often embodied the dark side of the sexual revolution that was also underway, taking license with students, who often felt pressured by their immediate culture to give way and who found little support when they complained.

In the 1960s, four major Zen teachers came to the United States from Japan: Shunryu Suzuki, Eido Shimano, Taizan Maezumi and Joshu Sasaki. Andy Afable, a former resident monk at a monastery founded by Eido Shimano Roshi, told me that three of the four—Maezumi and, more recently, Shimano and Sasaki—caused widely publicized sex scandals that brought great distress to their zendos and organizations. Even the one who was not tainted by scandal, Shunryu Suzuki, handed the San Francisco Zen Center off to Richard Baker, who became embroiled in scandal after it surfaced that Baker had had carried out affairs with several female members of his community.

Joshu Roshi’s impropriety with many of his female followers—and the collusive secrecy of his male followers—should not be forgotten. But it would be wrong to reduce the man to just this. He did have a grand side. “He’s both the friend and the enemy,” Leonard Cohen said of Joshu Roshi in the film Leonard Cohen: Spring 1996.

He is just what he is. And of course he’s going to be an enemy to your self-indulgence, an enemy to your laziness, he’s going to be a friend to your effort. . . . He’s going to be all the things that he has to be to turn you away from depending on him. And finally you just say: This guy is absolutely true. He really loves me so much that I don’t need to depend on him.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.