When I was around 15, I began to have a disturbing experience with a mirror. It would happen when I stepped into the bathroom next to my bedroom. Glancing at my own reflection, I would feel a kind of shudder and think: Who is that? It was a feeling of the utter strangeness and somehow flukiness that, of the billions of human beings that I might have been, I should be this particular one, with this particular face, looking out at me from the mirror. At first the experience happened only occasionally, but gradually it began to happen so often that I began to dread stepping into the bathroom. It was not just disconcerting, but profoundly disorienting, to encounter the stranger in the mirror who seemed to lie in wait for me, asking: Who do you think you are?

Gradually, the experience grew less and less intense for me and then faded away altogether. But when I began to read the opening pages of The Face: A Time Code, it all came rushing back to me. Remembering the dread, the fear of profound disorientation, I couldn’t help but marvel at Ruth Ozeki’s willingness to undertake the experiment that, moment by moment, she records in her book.

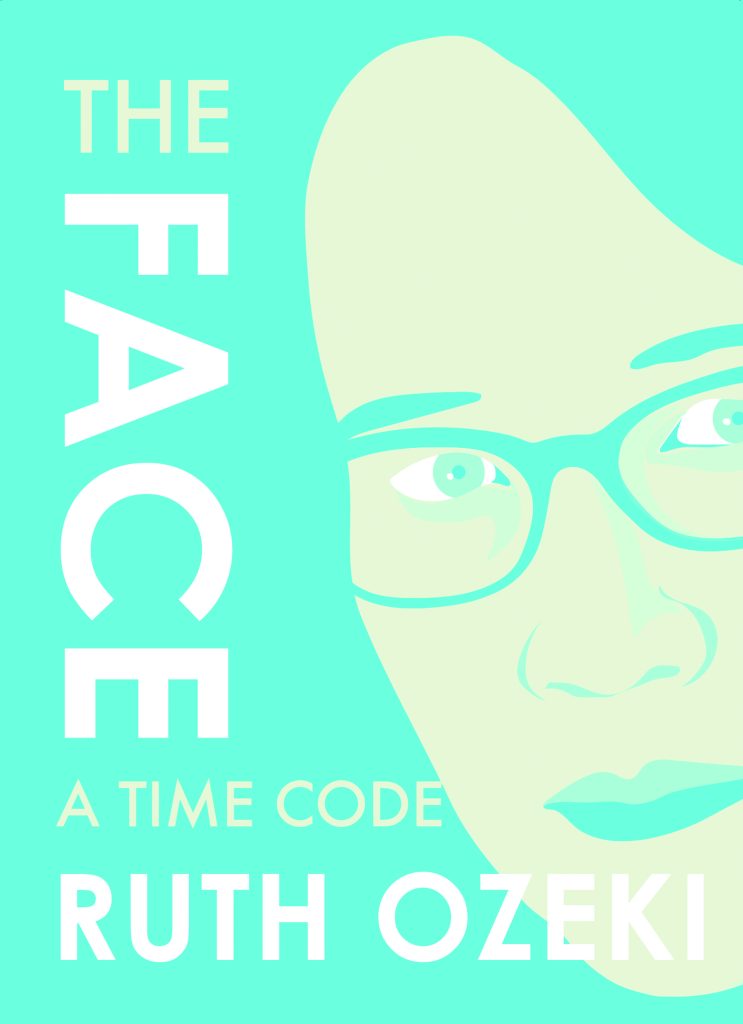

Ruth Ozeki, who is an ordained Zen priest, is the author of three novels: My Year of Meats; All Over Creation; and A Tale for the Time Being. Her latest offering is not a novel; it is the third in a series of very compact memoirs, published by Restless Books, each of which is an exploration of the writer’s face, with its own unique blend of personal and cultural history. (The other two in the series are The Face: Strangers on a Pier, by Tash Aw and The Face: Cartography of the Void, by Chris Abani.) Ozeki begins her exploration by invoking the famous Zen koan What did your face look like before your parents were born? It’s a question that continues to reverberate as she sits down, for three hours, to stare into a mirror. The experiment, she explains, was inspired by Jennifer Roberts, an art historian who teaches at Harvard University and who asks her students to spend three hours observing a single work of art, keeping a detailed account of their experience. The assignment is designed to cause discomfort, to force students to struggle with their own restlessness and impatience, pushing past their own most superficial responses in order to see, moment by moment, layer by layer, what the painting or sculpture might reveal of itself. For Jennifer Roberts, quoting the art historian David Joselit, a work of art is a “time battery,” a reservoir of the artist’s hours of concentrated labor, an “exorbitant stockpile” of information. The metaphor appeals to Ruth Ozeki, who approaches her own face as a time battery, a reservoir of the hours, months, and years of her own life experience.

Though the book (which she herself refers to as an “essay”) is arranged in tiny chapters, it’s essentially a log, a moment-by-moment chronicle of her observations:

00:00:00 I’ve put the mirror on the altar where the Buddha used to be. Laptop’s just below it. Fussing now with the seating, arranging the cushions. How close should I be? How much proximity can I tolerate? How is the lighting? Flattering? Unflattering? Does it matter? Should I change into a turtleneck to hide the lines on my neck? Hide them from whom? Is the neck even part of the face, and do I need to wash my hair? Do I need reading glasses, or can I type without them? Can I see without them? No, no glasses. No need to look at the computer screen. Just face and me, facing off in the mirror.

It’s clear that from the beginning she herself feels somewhat daunted by the challenge she’s undertaken. What makes the book irresistibly readable is to see how, moment by moment, Ozeki stays with the challenge. Floating down the stream of her own consciousness, she follows the free association of thoughts that arise in response to her own face. Given that the whole time she’s sitting in one spot before the mirror, it’s remarkable to see how far this river journey takes her. The last book I’d read of hers was For the Time Being, a complex novel with a fuguelike structure of interwoven voices that shimmer through the arc of the book, like ever more richly resonating chords. Though The Face is much simpler in its form, as I read I found that its single melodic line began to resonate in a similar way, through layers of time and gaps of both cultural and geographic distance.

At 59, Ozeki finds it difficult to look at her face without getting pulled into eddies of self-criticism: the puffy eyes, the thinning lips. . . . But as she continues to stare, the faces of her own younger selves emerge, along with the faces of her progenitors. Of European descent on her father’s side and Japanese on her mother’s side, her face reveals layers of both personal and cultural history, stirring memories of her Christian grandparents and her Zen Buddhist grandparents, of learning to make masks in the Japanese Noh tradition, of people looking at her mixed-race face and blurting out the question: What are you? At each bend in the river of thoughts, different emotional states arise: amusement, sorrow, anxiety, boredom, wonder.

In some ways, you might say, what the book is really about is the process of staying with: staying with one’s thoughts, even when they become boring or painful; staying with one’s face even when it is no longer so young and pleasing to look at; staying with one’s life, even as the losses loom and gather. As I read the book, I kept hearing in my mind a verse from the Chinese poem “Affirming Faith in Mind” that we used to chant every day at the Rochester Zen Center:

To founder in dislike and like is nothing

but the mind’s disease,And not to see the Way’s deep truth disturbs

the mind’s essential peace.

In an honest and unadorned way, as Ruth Ozeki dares to stare at her own aging and unadorned face, she simultaneously dares to share with the reader her own mind’s foundering in dislike and like. And because she dares to stay with the foundering—whether what she sees is unbearable, beautiful, or somewhere in between—the mind’s essential peace, her own original face, keeps shining through.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.