When she first encountered Kadampa Buddhism 20 years ago, Ani Jamgyal liked that it offered modern Buddhist teachings adapted to today’s Western society, without the trappings of another culture and its history.

“I have no nostalgia for old Tibetan feudal politics,” she says, “and I have no desire to learn how to make butter tea or eat tsampa.”

Ani Jamgyal, a 63-year-old Buddhist nun who is the daughter of a Baptist minister and lives in the mountains outside Albuquerque, has no interest in meddling in Tibetan politics or traveling to the East, because, she says, there are enough problems here in the United States. As a social justice activist who cares about such issues as racism, immigrant rights, and poverty, she wanted not to escape into the exoticism and problems of another culture but rather to find pure Buddhist teachings that could be applied to the problems of the present. “What drew me to Buddhism were its teachings, not everything around it,” says Jamgyal.

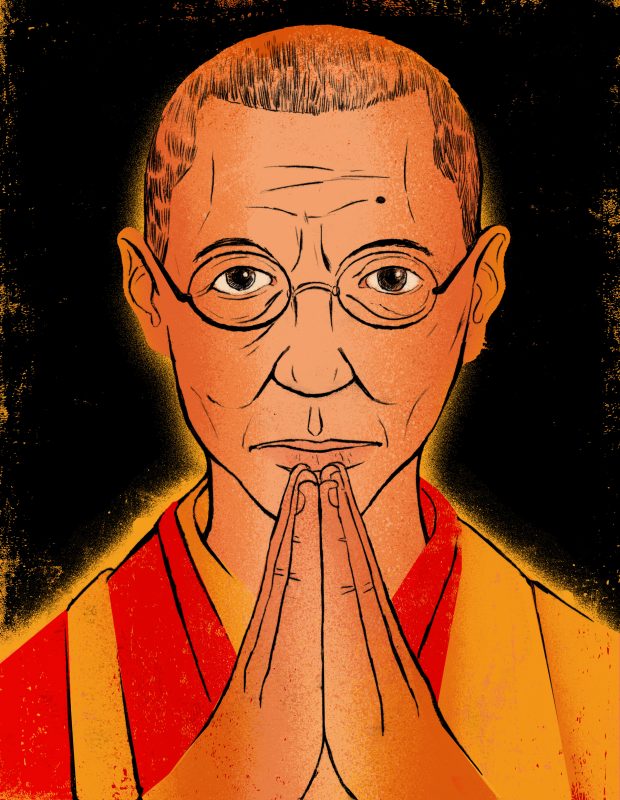

That’s what she thought she had found in Kadampa Buddhism, a new Tibetan Buddhist tradition that also goes by the name New Kadampa Tradition – International Kadampa Buddhist Union (abbreviated to NKT-IKBU, or just the NKT). New Kadampa Buddhism was established in 1991 in Britain by Geshe Kelsang Gyatso (affectionally called Geshe-la by his disciples), a Tibetan lama born in 1931 in Central Tibet, who in the ’70s came to Britain to teach Buddhism.

Many Westerners have been drawn, like Ani Jamgyal, to the NKT’s systematic study program, which offers a simple process of ordination and books that explain Buddhist philosophy and practice in terms that are easily understood by Western audiences. The NKT has been so successful in attracting Western practitioners that it is already one of the largest Buddhist traditions in Britain and is growing in the US and globally, with 1,200 centers currently open worldwide and new centers opening up all the time. Just this year, new NKT temples and centers have opened in Boston; Washington, DC; Fort Lauderdale; Oslo; and Paris. The International Kadampa Retreat Center near the Grand Canyon in Arizona, which opened its doors in June 2017, has started construction on the fifth Kadampa World Peace Temple, which will seat close to a thousand worshippers. The organization has also expanded quickly in countries such as Mexico and Brazil, and the NKT’s unique canon of texts has been published in English, Spanish, Portuguese, German, French, and Chinese.

Unlike most Buddhist traditions, the NKT asks ordained members to take only ten vows, which according to Kelsang Gyatso replace all the hundreds of vows usually required of ordained Buddhists. “If it were not for the NKT,” says Ani Jamgyal, “I probably would not have chosen to become a nun.”

But Jamgyal discovered that the NKT was not as far removed from “feudal Tibetan politics” as she had hoped. By joining the NKT, she was in fact being pulled into a religious conflict dating back centuries and had inadvertently become a member of an organization that has been accused of being sectarian, controversial, and so concerned with religious purity that it has isolated itself from the wider Buddhist world. It turned out that as a member of the NKT, Jamgyal was expected to denounce the Dalai Lama and reject all spiritual teachers besides Kelsang Gyatso, who is viewed by many NKT members as the sole holder and savior of pure dharma.

“Kelsang Gyatso is the source of all authority in the NKT,” says David Kay, a British researcher who wrote his PhD thesis on the organization’s formation. “The NKT presented his books as the emanations of the mind of a Buddha.”

Kelsang Gyatso’s decision to split off from the Tibetan Buddhist establishment and create a new tradition was in fact the culmination of an old conflict about a protector deity associated with the Gelug school named Dorje Shugden. Shugden is entrusted with guarding the purity of the teachings of the 14th-century master Je Tsongkhapa and is said to punish and terrorize wayward monks who take an interest in the teachings of competing Buddhist schools. Gelug Buddhists see Tsongkhapa as a reformer who restored the purity of Buddha’s doctrine in Tibet after other Buddhist schools had lost their way. The Gelug school was originally a small movement that challenged older Tibetan Buddhist schools, but it quickly grew in popularity and in the 17th century, under the leadership of the 5th Dalai Lama, became the dominant Buddhist order in Tibet.

“There has always been a strongly sectarian stream in Gelug Buddhism,” says Georges Dreyfus, a professor of religion at Williams College who is the first Westerner to have completed the Geshe Lharampa degree, the most advanced Tibetan Buddhist academic degree, in Dharamsala. Dreyfus explains that Dorje Shugden already existed as a minor wrathful deity in the Gelug tradition by the 17th century. But with the rise in popularity, in the early 20th century, of the ecumenical Rimé movement, which argues that different Tibetan Buddhist traditions all offer equally valid paths to the dharma, the conservative Gelug elite felt that the supremacy of the Gelug school was threatened. Pabongka, an influential Gelug monk in Lhasa, promoted the worship of Dorje Shugden in order to preserve Gelug purity and discourage Gelug monks from adopting the Rimé movement’s inclusive philosophy. Pabongka passed his sectarian views on to his disciple Trijang Rinpoche, who later became the current Dalai Lama’s junior tutor and introduced the young Dalai Lama to Dorje Shugden.

Everything changed when the Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959 to escape the Chinese occupation. In exile, the Dalai Lama concluded that Tibetan unity was more important than the supremacy and purity of the Gelug tradition, and he adopted the inclusive outlook of the Rimé movement. Tensions built steadily as he distanced himself from Dorje Shugden. Eventually, he demanded that Gelug practitioners refrain from worshipping the deity entirely, which caused a rift in the Gelug school. A number of Gelug lamas in the Tibetan exile community, most of them disciplines of Trijang, turned against the Dalai Lama.

“Some NKT practitioners are absolutely certain this is the last opportunity to find pure Buddhism in the world, and that everything else is corrupt.”

Among the most vocal of the protestors was Kelsang Gyatso, who had been sent to England originally to teach Gelug Buddhism and who had meanwhile gained the loyalty of a number of committed students. Kelsang Gyatso was so aggrieved by the Dalai Lama’s rejection of Dorje Shugden that he decided to split off from of the mainstream Gelug establishment and branch off on his own. With the help of his senior disciples, he translated the key texts of his lineage into English and in 1991 created a completely Western tradition in which he was the only Tibetan: the New Kadampa Tradition, named after the medieval Tibetan Kadam school that later developed into the Gelug tradition.

David Kay says the NKT sees Kelsang Gyatso as a figure similar to Atisha, the 11th-century Bengali Buddhist sage who founded the Kadam school and safeguarded the pure dharma by transmitting his teachings in Tibet while Buddhism was in decline in his native Bengal.

“Some [NKT] practitioners are absolutely certain this is the last opportunity to find pure Buddhism in the world, and that everything else is corrupt,” says Kay. He has encountered NKT disciples who not only avoided the teachings of other Buddhist schools but also would not even read the English translations of texts by Kelsang Gyatso’s own teachers, because they said they distrusted any text that was not by Kelsang Gyatso himself.

Kelsang Gyatso’s own texts follow mainstream conservative Gelug teachings, but once transported to the West, the Gelug emphasis on pure lineage was taken to the extreme. NKT teachers are, for example, expected to memorize Kelsang Gyatso’s texts so that they can faithfully reproduce his teachings without confusing students with misguided interpretations.

“To teach is to be essentially given a script,” says Gen Kelsang Wangden, a 44-year-old monk who is the resident teacher of Menlha Kadampa Buddhist Center in Lambertville, New Jersey, adding that the teachings he has been given are “really clear and really effective and beautiful.”

In 1996, when the Dalai Lama instructed Tibetan Buddhists to refrain from worshipping Dorje Shugden, denouncing the deity as “a malevolent spirit that arose out of misguided intentions,” he provoked the fury of Shugden devotees. (In that same year, Kelsang Gyatso was officially expelled from Sera Je Monastic University in India; the expulsion notice read that he was expelled for “blatantly shameless mad pronouncements attacking with baseless slander His Holiness the Dalai Lama.”) The NKT, which had placed Dorje Shugden at the center of its worship—Kelsang Gyatso considers Dorje Shugden a buddha—organized demonstrations and letter-writing campaigns to denounce the Dalai Lama’s “religious oppression.” Twenty years later, in 2015, Reuters reported that the NKT was behind a protest group, the International Shugden Community, that organized demonstrations against the Dalai Lama when he visited the US. At every destination on his tour, the Dalai Lama was met by groups of protestors—many of them NKT members—who heckled him with slogans such as “False Dalai Lama, give religious freedom!” and “Dalai Lama, stop lying!”

“Geshe-la was part of a tradition that was lost in Tibet, just as the Tibetan government in exile itself is lost now,” says Gen Kelsang Chonden, a long-time British disciple of Kelsang Gyatso, and, when I saw him, Resident Teacher of the Bodhisattva Kadampa Meditation Centre in Brighton, England. He had been visiting the 2017 US Festival at the US Kadampa World Peace Temple in Glen Spey, New York, which hosted NKT members from all over the world. Dressed in long maroon Tibetan robes, Gen Chonden sat on the temple steps and talked about the decline of Buddhism in Tibet. He said that the Dalai Lama has not only betrayed his own teacher and tradition but also wants to “force others to abandon that tradition as well,” referring, of course, to the Dalai Lama’s position on Dorje Shugden.

The NKT itself is not directly affected by the Dalai Lama’s rejection of Shugden, but Chonden says the organization must protest the Dalai Lama’s stance on Shugden because millions of Shugden devotees are suffering persecution and have asked the NKT for help in preventing the destruction of their tradition. There is indeed evidence that Dorje Shugden devotees in the Tibetan exile community are socially stigmatized and marginalized. However, the NKT’s claims of persecution are wildly exaggerated, and Amnesty International has declined to investigate the NKT’s allegation of human rights abuses against Shugden worshippers, citing lack of evidence. In fact, devotion to Dorje Shugden is encouraged by the authorities in Chinese-controlled Tibet—in 2015, Reuters published an article that exposed China’s use of the Shugden conflict to undermine the Dalai Lama and position itself to control the selection of his next incarnation. [See “The Red Lamas.”]

Still, Chonden insists that the Dalai Lama is suppressing freedom of religion and destroying his own spiritual lineage. “In the Tibetan exile community in India, Buddhism has become politicized,” he says. “We are grateful that Geshe-la has preserved the pure Mahayana teachings for us.”

After several years in the NKT, Ani Jamgyal finally realized that Kelsang Gyatso’s feud with the Dalai Lama meant he expected his disciples to campaign publicly against the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan Government in Exile. In 2011, Jamgyal decided to distance herself from the organization. She had tried to ignore the Shugden conflict because she appreciated the clarity of Kelsang Gyatso’s teachings, but it became impossible to separate the teachings from the politics that came with them.

“Part of it was realizing how completely isolated that group is from the rest of the whole Buddhist world,” says Jamgyal. “It felt as if I were doing something naughty when I was reading books by other teachers, including His Holiness—and it’s just crazy that reading dharma made me feel as if I were 16 and smoking a joint behind a garage!”

Renato Barajas, a monk from Mexico who ordained in the NKT in 2013 and left the organization in 2017, had an experience similar to Jamgyal’s. He says that while NKT seems to newcomers like an open, welcoming organization, it becomes increasingly restrictive and controlling once practitioners are drawn inside. “The NKT has two different faces: one is for the media and the public, and the other is for the people inside the NKT,” he says.

Kelsang Gyatso, who turned 87 in June 2018, withdrew from public life in 2013 and has not been seen in public since then; the NKT is now led by his senior disciples. A General Spiritual Director is elected for an eight-year term to oversee the spiritual development of the tradition. The current Director is Gen-la Kelsang Dekyong, a British nun who has studied with Kelsang Gyatso for over 30 years. Neil Elliott, Kelsang Gyatso’s original “heart-disciple,” had to give up his robes in 1996 because he broke his monastic vow of celibacy. (Elliott ran the NKT teacher-training program as a lay practitioner until reinitiating as a monk in April 2017 with the name Gen-la Kelsang Thubten; he has now taken a role as a senior teacher.) Despite Kelsang Gyatso’s reclusiveness, however, Geshe-la is still the ultimate authority of the organization and remains present in his writings.

According to Barajas, advanced NKT disciples are told that Kelsang Gyatso is a buddha who watches over them and guides their lives. He is venerated as an infallible source of wisdom, and some disciples have even speculated that he may be the third Buddha, which would elevate him to the same spiritual level as Je Tsongkhapa, whom many Gelug Buddhists consider the second Buddha, and the same level as Siddhartha Gautama, the first Buddha.

Critics of the NKT say that such devotion to Kelsang Gyatso is unhealthy—indeed, they argue that such certainty of faith requires a closed-mindedness that to many seems out of place in a modern, pluralistic world. Geshe Dakpa Topgyal, for one, is wary.

“Nobody can claim to be the only one to know the truth,” says Topgyal, a Gelug monk with a geshe degree from Drepung monastery in India who now leads the Charleston Tibetan Society in South Carolina according to Rimé philosophy. “The problem is that Kelsang Gyatso wants his disciples to see him as the only legitimate one, the only one who is qualified. There is no room for critical thinking. This is dangerous in every aspect!” Geshe Topgyal points out that the Buddha himself warned against “blindly clinging to one’s own view and thought.”

This danger isn’t mere theory—the NKT’s modus operandi has led to several real-life consequences for its members. Former NKT member Jamie Kostek, who joined the NKT sangha in Seattle in 2007, when she was 24, and left in 2012, has personally observed the dangers of blind devotion. “Everyone looks so happy when you come in,” says Kostek. “You have no idea of all the suffering going on behind the scenes.” She says she felt pressured to constantly convince herself she was happy in the NKT, because unhappiness is a sign of spiritual failing. “And we truly felt fortunate to have these teachings,” she says, “because we were constantly told that this is the only path that will lead to nirvana.” She believed that if she completely devoted herself to Geshe-la, she would attain enlightenment in three years, three months, and three weeks. “Then, when you’re still not enlightened, you’re convinced you did something wrong and did not dedicate enough of yourself to Geshe-la,” she explains. “So you become ordained or give away all your money to prove you’re worthy.” Kostek had no money to give, but she often volunteered 35 hours per week for the organization while holding down a job and taking care of her young son. “I felt I had to do it to gain spiritual merit,” she says, and adds that she worked herself into such exhaustion, she did not even have time to meditate.

But Kostek started questioning the NKT when she noticed how the organization treated its most vulnerable members. She says some of the ordained people in her community who struggled with serious mental illnesses were encouraged to go off their medications and try to heal themselves through spiritual practice. She also tells the story of an elderly nun who had been encouraged to sell her house and donate the proceeds to the NKT—and then paid rent to live in a basement at the NKT center. Kostek explains that there was constant pressure in the NKT to contribute to its International Temples Project, which aims to build Kadampa temples around the world.

“When you’re still not enlightened, you’re convinced you did not dedicate enough of yourself to Geshe-la.”

According to INFORM, a British nonprofit organization that investigates new religious movements, the NKT’s finances in Britain have been able to grow through shrewd real-estate investments financed by member donations and properties restored through volunteer construction work. But when members have spoken up to question decisions or mismanagement, the NKT’s leadership has been unwilling to listen. INFORM also reports that the NKT has regularly tried to silence critics by using British libel laws as a threat. (In one such case, the British Buddhist scholar Gary Beesley was forced to withdraw a book about the NKT just before its publication date.)

Despite this pressure, some critics of the NKT remain outspoken. One is Tenzin Peljor, a former NKT practitioner from Germany who, after having been involved with the NKT for more than five years, left the tradition and reordained as a monk with the Dalai Lama. Tenzin Peljor, who says he now leans towards the Rimé philosophy, has run a blog for some time called Struggling with Difficult Issues, in which he has addressed controversial topics in Tibetan Buddhism.

Tenzin recounts that when he was still in the NKT he himself used to turn a blind eye to problems in the community, because he clung to the notion that he had to maintain a “peaceful state of mind.”

“They keep telling you that you have special karma to have become part of this exceptionally pure tradition,” he says, “and then your ego gets hooked, and you become delusional because you are cut off from mainstream Buddhism and other sources that can correct your delusion. And after you have committed 10 or 12 years, it takes enormous bravery to admit that you made a mistake.”

Tenzin Peljor has strong opinions about Kelsang Gyatso himself. He describes the NKT leader as a narcissistic personality who sees himself as the sole savior of pure Buddhism. “His mind is manifest in the culture of the NKT,” says Tenzin, adding that the result is an organization so fixated on spreading Kelsang Gyatso’s teachings that it is willing to sacrifice the well-being of its practitioners to expand and attract new students.

“This is a personality cult,” says Tenzin.

When contacted for a response, a representative for NKT’s US headquarters wrote, “According to the NKT’s constitution, the NKT cannot be involved in political activity. For this reason the NKT does not accept any requests for interviews.”

“The NKT is the end result of a long trajectory of radicalization,” says Professor Dreyfus of Williams College. He remembers Kelsang Gyatso as someone who had a reputation as a learned monk, and says Gyatso’s former colleagues are puzzled. “The whole thing is bizarre. Kelsang Gyatso’s books are good. He is smart. He is learned, he is a good practitioner,” says Dreyfus. “Many Tibetans who knew him told me they don’t understand. They thought they knew him, but now they have no idea what he is doing.”

Dreyfus is convinced that if Trijang Rinpoche were alive, he would disapprove of what became of his former pupil. “I knew Trijang Rinpoche very well, and I know that he would be positively horrified by the NKT if he were alive now,” says Dreyfus. “It’s inconceivable that he would have allowed this to happen.”

For her part, when Ani Jamgyal left the NKT, she wanted to remain a nun and so found a new teacher, who reordained her: Thrangu Rinpoche, a Kagyu teacher who belongs to the ecumenical Rimé movement. Jamgyal says she was touched when she first showed up at a teaching and was told she did not need to worry about having to renounce Kelsang Gyatso in order to become a disciple of Thrangu Rinpoche. “We are not sectarian,” she was told. “In our view you have simply expanded outward from the NKT to include us.”

The return to the “right” or “pure” dharma is one that Buddhists have sought ever since the Buddha’s death.

Jamgyal still appreciates how much she learned from Kelsang Gyatso’s writings, and she insists that she has not encountered any mainstream Buddhist teachings that contradict Kelsang Gyatso’s books. But her experience in the NKT has made her suspicious of Buddhist communities. Her takeaway is that there is always potential for abuse and sectarianism in any religious community. She is now reluctant to align herself too closely with any particular tradition and prefers to remain a solitary practitioner.

“I don’t understand this whole conflict. And I don’t care,” she says. “I just want to understand what the Buddha said.”

Many will recognize their own hopes in Jamgyal’s aspiration. The return to the “right” or “pure” dharma is one that Buddhists—including those in the West—have sought in various ways and in varying degrees ever since the Buddha’s death. The NKT is perhaps just one especially extreme example, an organization whose ideology has thrived in part because its members are from a social environment in which Buddhism is still new—meaning that they come to the NKT lacking a wider perspective on Buddhist history. Then, when they are discouraged from engaging with Buddhism’s broader dialogue, their views remain narrow.

To anyone searching for the one truth, Georges Dreyfus has a response: “Good luck with that!” He explains that even the earliest Buddhist texts may not reflect the exact words of the Buddha, since they were composed long after the Buddha had passed away. “What we are left with is not what the Buddha said but how the Buddha’s ideas and practices have been appropriated and transmitted by the various Buddhist traditions,” says Dreyfus. He sees this not as a problem, but as a beautiful intellectual richness that has sprouted from the original teachings of the Buddha. Of course, this richness does not provide one clear answer about what the Buddha taught, and its resplendence is dulled by centuries of religious polemics and conflicts. This is why Dreyfus advises practitioners to educate themselves about the history of Buddhism and the positions of the tradition they choose to follow—“so they can separate the teachings from the political baggage that comes with it.”

The Red Lamas: The politics at play in the Dorje Shugden conflict

When the Dalai Lama in 1996 urged Tibetans to end the worship of the Gelug protector deity Dorje Shugden, he intended to strengthen Tibetan unity and promote harmony among the various Tibetan Buddhist schools. But although the majority of the Gelug community sided with the Dalai Lama, others refused to give up their worship of Dorje Shugden. Those monks, expelled from mainstream Gelug monasteries and marginalized in the Tibetan exile community, have established rival monasteries and sought new communities to support their teachings. Kelsang Gyatso, the founder of NKT, is one of these monks, but there are many more. Most of them share a lineage that traces back to Trijang Rinpoche, the Dalai Lama’s former teacher and a committed Shugden devotee.

According to the French Tibetologist Thierry Dodin, “Shugden lamas” have gained support in places such as Mongolia, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Some have developed a warm relationship with China’s government, which has embraced the conflict to weaken the Dalai Lama. Although the Communist Party is secular, it tightly controls religious worship and has been promoting Dorje Shugden in Chinese-controlled Tibet. It has been reported that the Party has treated prominent Shugden lamas as honored guests and that Shugden activists have been receiving clandestine support. China also controls its own chosen Panchen Lama, historically the second most powerful lama in the Gelug lineage, who traditionally plays a key role in recognizing the next Dalai Lama. According to Dodin, the young Panchen Lama has been educated by Shugden lamas selected by the Chinese government.

♦

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Ani Jamgyal, after leaving the NKT, was reordained by Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, an ecumenical Nyingma teacher. She was reordained by Thrangu Rinpoche.

Learn more about the Dorje Shugden controversy in Tricycle’s 1998 Special Section, “Deity or Demon?”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.