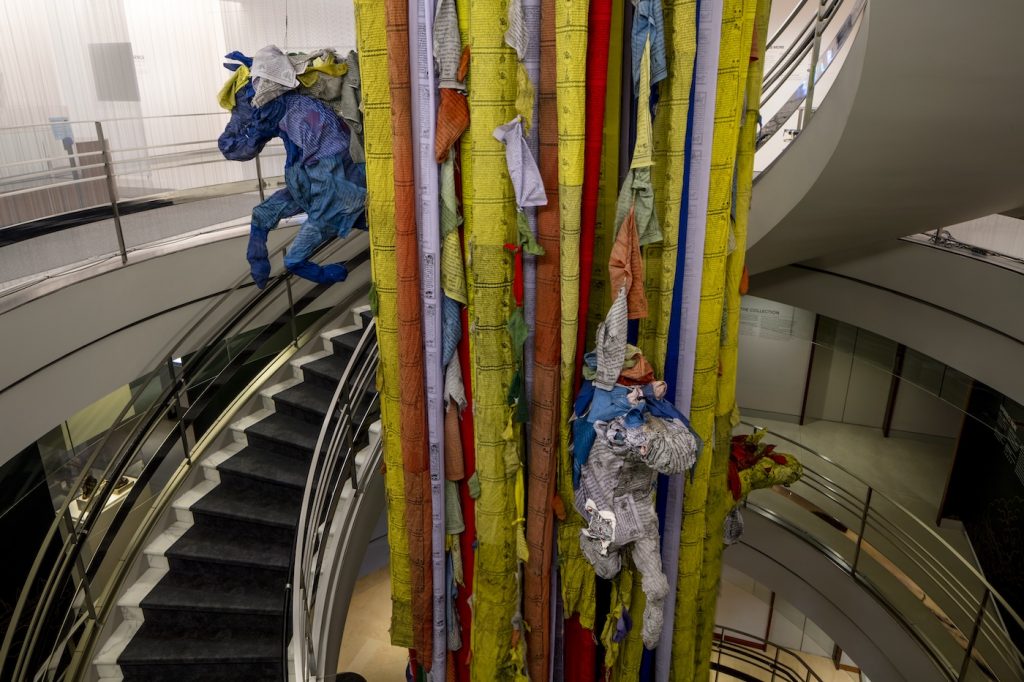

Cascading down five flights of the spiral stairwell, in the center of the Rubin Museum’s atrium, hangs artist Asha Kama Wangdi’s sculptural installation The Windhorse (lungta). Composed of prayer flags fastened around a metal skeletal frame, windhorse figures emerge between and throughout the fabric canopy suspended from the museum’s sixth floor. Nearby, and positioned in conversation with The Windhorse (lungta), sits a 16th-19th-century carved woodblock print, depicting a yantra diagram. Together, the museum relic and contemporary installation invite a fleeting quality of transience into their shared and unfixed landscape of prayer.

On the opening night of “Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now”—which marks the closing of the Rubin Museum’s Chelsea exhibition halls—Bhutanese multidisciplinary artist, lay practitioner, and community organizer Wangdi debuted his “Wasted Prayers” concept, which comments on the spiritual irony and adverse effects of synthetic prayer flags. The mass production and designed durability of the prayer flags in the later half of the 20th century has recently come into focus for its deleterious environmental impact, as discarded remnants pollute the Himalayan region.

Although this concept has taken many forms over the last three decades, The Windhorse (lungta), commissioned for the “Reimagine” show, has placed Wangdi and his community of contemporary Bhutanese artist-collaborators in the international spotlight and public eye.

Wangdi, who grew up in Punakha, Bhutan, a village two hours by car outside the capital city of Thimphu, had been fascinated by the craft of traditional Bhutanese fine art from an early age. His interests landed him in cultural preservation and illustration work for the National Fine Arts Centre and the Bhutanese Royal Government in Thimphu. In the early ’90s, an exciting scholarship to the Kent Institute of Art & Design introduced Wangdi to new mediums of storytelling through work in theater, film, graphic design, and fashion. While studying media, he worked within time-based mediums for the first time. This opened new doors, coming from a background in fine art.

Wangdi was inspired to expand Bhutanese artistic expression beyond the long-admired forms of Bhutanese fine art exhibited in religious and preservation-minded cultural settings. In 1997, he cofounded VAST (Voluntary Artists Studio, Thimphu), an arts education center, which aims to nurture the work of contemporary artists and artistry in Bhutan today.

Tricycle recently talked with Wangdi about the genesis of his creative expression, the concept of “Wasted Prayers,” and his hopes for the future of VAST and contemporary art in Bhutan.

*

I loved your piece The Windhorse (lungta) at “Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now.” Can you speak to the creation and meaning behind this piece? You may be familiar with lungta flags. Hosting lungta is a big thing here in the Himalayas—especially in Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, and India.

There are two historic forms of prayer flag creation:

1. Originally monks would chant windhorse prayers and then write the prayers down for us to host.

2. Then, when block printing came on the scene, we started to see flag-hosting in greater quantities.

In ancient Bhutan, when there was no technology to mass-reproduce prayer flags, I heard older monks maintain that prayers used to be exclusively handwritten on paper or cloth. And so back then we were hosting fewer flags. Now, with technology and mass production facilities, we actually have a problem of excess. In Nepal, wild animals are being strangled by prayer flags. Even high up in the mountains, in Tibet, the yaks are getting caught in the prayer flags. Prayer flags are being reproduced with toxic inks and polyester fabrics for long-lasting durability. In actuality, the prayer flags shouldn’t be long-lasting. Aligning with the practice of impermanence, the prayers should disintegrate into the wind.

When I was studying in the UK in the late ’80s, I worked on some project ideas using discarded prayer flags, calling them “Wasted Prayers.” The intention was to highlight the contradiction of hosting the flags with good intention, while the result is negative, because we are not hosting them in the right way.

I think the scriptures are the highest form of icon—it’s the speech of an enlightened being. So when the scripture, which has been respected by the teaching of an enlightened being, gets littered on the ground, in unhygienic places, and soiled with impurities, we are unintentionally causing bad virtues.

By repurposing the discarded flags into artwork, in my own small way, I was trying to give one more chance to the prayers.

By repurposing the discarded flags into artwork, in my own small way, I was trying to give one more chance to the prayers. My process involved recreating my paintings using these discarded flags, in a collage mixed-media style. I feel better knowing that whatever I pick up from the ground will be put on to a canvas and made into art. That way, the flags won’t end up under the bed, or in a toilet, or in another unhygienic environment.

Then, when I gift the artwork to people, they have this renewed respect for the prayer flag. Instead of throwing it away, they want to hang it up on the wall. When this happens, it’s like the windhorse has one more chance. It is safer on the wall than on the ground. That was my intention with the project.

This is the last show at the Rubin before they close their doors. What does it mean for you to have your work highlighted at this event? I think for all of the artists, particularly those from Bhutan, having the opportunity to participate in the “Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now” exhibition was a big deal. The Rubin Museum provides the rare opportunity for lay Buddhists like us to see all of these religious icons and objects together in one place. In Tibet or Bhutan many of these religious icons have been consecrated, [stolen, or destroyed]. There is artwork inside the statues and temples, but we have no access to them. There is no visual contact. The Rubin gave us the opportunity to view all these artifacts and icons together under one roof, where we have access to visit, make offerings, and get blessed.

How has your spiritual practice influenced your creative and professional aspirations? I call myself a lay Buddhist because I don’t read the scriptures, I don’t sit to meditate and pray, and I don’t have religious routines—but many lay Buddhists are quite spiritually aware. I request that the monks offer prayers, while I offer compassion and practice no harm. That is a fundamental aspect of our Buddhist practice.

When you’re approaching anything with your full attention, whether it is creating a painting or practicing compassion—whatever you’re focusing on—it’s a form of spiritual practice because it takes away your mind, and your essence is focused. If you’re concentrating, you’re not roaming around—there’s no monkey business. While I’m creating, I have no time to think badly about other beings. In this way, my art practice is like a spiritual practice.

How did creating this site-specific installation for the Rubin change or challenge your creation process? The public, far-reaching environment of the Rubin was very exciting. The concept of the windhorse is to raise some kind of awareness of everyone’s potential to harness good energy. The sculptural element of the horse coming out of the prayer flags served as a reminder of the good thing in each of us. It felt akin to releasing blessings visually. By sharing and displaying this concept in the Rubin, we hope that more people will engage with the concept of the windhorse.

We were so fortunate to get the space to design a piece that crossed five floors of the museum, reflecting the five elements of the prayer flags and their expressions.

Can you please name the five elements of the expressions? The five colors of the windhorse are symbolized by the five elements that are crucial for sustainability and well-being—space (green), the sky (blue), fire (red), art (yellow), and air (white). The five elements are spiritual but, at the same time, very practical. Any one of us can express this in this framework.

In the mission statement of VAST you claim to foster a uniquely Bhutanese aesthetic in your art mentorship. Can you describe what that looks like? In Bhutan, our architecture, murals, regalia, and the patterns and colors with which we adorn our homes are very similar to those of Tibet—but there are key differences. I incorporate these distinctions into my mentorship practice at VAST when our team workshops on how to communicate contemporary expressions of our traditional art form. For example, we have symbols that we draw on windows, which help us to correct our energy and subdue the hindrances. They also protect us from outside influences.

I also share with them how Bhutanese song and dance resemble core teachings of spiritual practices and religious philosophy in simple and direct ways.

Bhutan has cultural museums and art institutions, but they are focused on preserving traditional forms of art. I’d like to see a national gallery that showcases the work of contemporary artists.

As an artist and educator, you balance two very important and different aspects of the creative process, honoring your own practice as well as mentoring others—how would you describe the balance between your work and helping others? It’s quite tricky, actually. For the last twenty years or so, I’ve worked for the National Government of Bhutan as an extra hand. My artistic practice was limited by the projects that the government placed me on. I was told what to paint and how to design—which is not uncommon, but there was no freedom or creative liberty.

When I left this role, I got involved with mentoring other people’s creativity. My focus shifted to building collaborative projects with the youth and elders of my community. The creativity was focused through an educational lens, which also relies on artistic expression. But again, I really had to find balance between working for my sustainability and my own satisfaction.

Three years ago I realized, My time is limited. I want to revisit my own creative expression. Since then, I’ve been painting things I’ve always wanted to paint. I’ve been getting more hands- on, while also still supporting younger artists.

What does the future hold for VAST? VAST began as an outlet to showcase the artwork of individual artists but quickly developed into a whole artistic community. It is a joint project for many of us. A lot of young people are taking initiative and showing an interest in building upon this collective.

Our work does not end with this installation. Getting the invitation by the Rubin to participate in the “Reimagine” exhibition really opens up a lot of possibilities for us, internationally. We have already expressed our interest to continue collaborating with the Rubin—or any other organization—to organize our own exhibition in Bhutan—like the windhorse festival—involving even more artists. We are also trying to organize a national diploma-level art program.

Bhutan has cultural museums and art institutions, but they are focused on preserving traditional forms of art. I’d like to see a national gallery that showcases the work of contemporary artists and also hosts art courses that will share traditional art and contemporary art alongside one another.

We are at a crossroads, and I am confident in the younger lot.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.