In a city rich with world-renowned museums and niche cultural institutions, the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art stood out as one of the finest. In a city known for its breakneck pace and nonstop pressure, the Rubin Museum also stood out as a quiet sanctuary amidst the hubbub. On 17th Street near Seventh Avenue in Chelsea, it was a place to collect one’s thoughts and open the mind. A place to learn, explore, and connect. And it still is, for now. But, reflecting the truth of impermanence underpinning some of the art on its walls, the twenty-year-old Rubin is changing form. On October 6, 2024, museum-goers will say goodbye to the modern facade, central spiral staircase, cherrywood auditorium, and dimly lit spaces encouraging contemplation. The illuminated antiquities from Tibet, Nepal, and all over the Himalayas will go dark as the Rubin closes its physical space and becomes what it is calling a “museum without walls.”

“With a long-term view, we’ve been carefully discerning new ways to fulfill our mission, and we believe that transforming into a global museum—a museum without borders—is a really exciting path for the Rubin,” Executive Director Jorrit Britschgi tells Tricycle.

This means that moving forward, the museum will focus on traveling exhibits, educational programs, research, multimedia projects, long-term loans, and supporting contemporary artists. A new website will launch in October with a fresh approach to content and more video, including videos that spotlight artists and their approach, and announcements about new offerings will continue to roll out in the coming months.

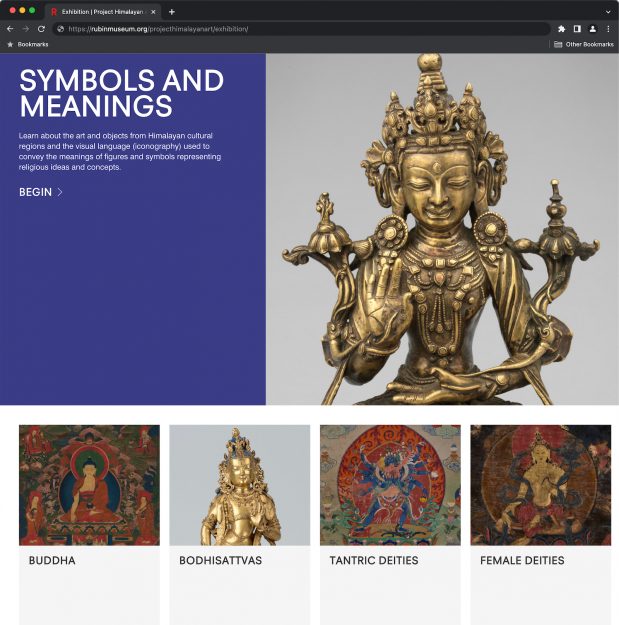

The museum has already found success with various traveling exhibits and programs, including the Mandala Lab in Bilbao and London, and the interdisciplinary resource known as Project Himalayan Art, which consists of a digital platform, scholarly publication, and traveling exhibition for colleges and universities. The museum has also expanded digital offerings in recent years with its AWAKEN podcast and Mindfulness Meditation podcast, both of which will continue.

“We’ve seen that these piloted programs have a huge impact and have reached people that we have not reached before, so this has really emboldened us in our decision,” Britschgi says.

In the last few years, as activism and action around art repatriation has grown, the Rubin has been in the news for returning relics to Nepal that are believed to have been stolen. Britschgi denied any connection between repatriation efforts and the museum’s decision, reiterating what the museum’s website says regarding its commitment to researching providence and ownership history, and its repatriation of three objects in the last two years. “Our ongoing commitment, and even expansion, of provenance efforts will continue and will not change as part of our new organizational model. However, the position that we’ve taken really has nothing to do with repatriation claims,” he says.

Regarding religious art and ritual objects specifically—artifacts that may require more context, another crucial part of the repatriation conversation in addition to providence and ownership history—Britschigi said that as a secular institution, the museum has tried to focus on original context, whether through the shrine room or engaging community voices. But this new model affords them the opportunity to concentrate on another way to enhance context: long-term loans.

“One of the important things that we’re doing going forward, and [that] we’ve certainly seen an outpouring of interest [in] from the museum community, is to invest in long-term loans—that is, to share our collections with other organizations to allow them to tell the story of Himalayan art more fully,” Britschgi says.

Another future emphasis the director highlighted is expanded support of contemporary artists—those inspired by or connected to the region. Among other initiatives, the museum will start grant programs to support emerging artists and scholarship and research in Himalayan art. In September, it will also introduce a new award—the Rubin Museum Himalayan Art Prize—to give visibility to contemporary artists.

As for the financial motivation for closing the physical space, although the museum let go of 25 percent of its staff, reduced opening hours, and cut programming in 2019, the FAQ section on the website denies that the Rubin is in financial trouble. A spokesperson told CNN that it was making this decision “from a position of financial strength,” and the New York Times reported that their endowment reached $150 million in 2023. In an email, Britschgi told CNN, “The significant resources required to own and operate a building in New York City will now be focused exclusively on our collection, exhibitions, programs and community of artists.”

Many fans of the museum are grieving the anticipated loss. Senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations Ian Johnson called it “a disaster for Tibetan art,” while Snigdha Sur, founder and CEO of the Juggernaut, a publication dedicated to South Asian stories, wrote, “This makes me quite sad. . . So few spaces feel dedicated to Asian culture.”

Acknowledging that it’s a bittersweet moment, Britschgi maintains his optimistic outlook for the future and hopes that fans visit 150 West 17th Street in the coming months to celebrate the museum’s twentieth anniversary, take part in the programming—including the anniversary exhibition, Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now (March 15–October 6, 2024)—and share memories in the space before its rebirth.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.