Philip Whalen and Gary Snyder were leading lights in 20th-century American poetry and in the establishment of Zen Buddhism in the West. This article, adapted from David Schneider’s upcoming biography of Whalen, tells of how their lifelong friendship, like other famous literary and dharma friendships, helped shape them both, as well as countless others whose lives they touched.

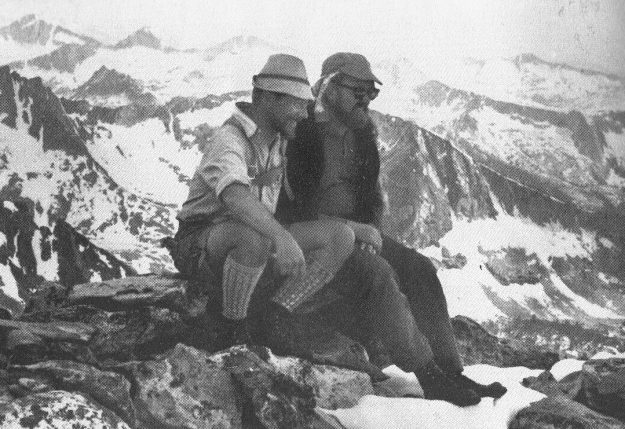

Philip Whalen had no better friend than Gary Snyder. Whalen’s life would have run a vastly different course had the 17-year-old Snyder not first seen him from offstage at Reed College’s theater, directing players in a student production, and been impressed with him. Whalen might have taken much longer to run across Zen writings, for example—Snyder brought D. T. Suzuki’s books home to their apartment when they were living together in San Francisco. Philip might never have found work in the mountains: sitting in that same Telegraph Hill apartment in the hot summer of 1952, Whalen read one of Gary’s regular letters, this one from a Forest Service lookout on Crater Mountain in the North Cascades of Washington State. Provoked by it, and by working (“bad anytime, but especially nasty in summer in the city”), Whalen wrote back to declare, “By God, next summer, I’m going to have a mountain of my own!” This he did; then got another mountain the following year, and spent a third summer as a forest lookout the year after that, making this by far his steadiest, most satisfying job until many years later, when he became a “professional” man of the cloth—that is, a Zen priest. Whalen would never have read in the historic Six Gallery reading had not Snyder put Philip’s name and poems literally in front of Allen Ginsberg’s face. Philip certainly would have floundered longer with unemployment and flirted more dangerously with outright homelessness had Gary not taken care of him whenever the two were in the same town at the same time.

They roomed together in San Francisco off and on from 1952 to 1954 in a flat on Montgomery Street, above the city’s North Beach district, to which they descended together nearly nightly for beer at Vesuvio and other drinking establishments. Thus Philip and Gary came to know the writers, players, merchants, philosophers, painters, filmmakers, musicians, and scholars circling around the Bay Area in the gestation phase of the San Francisco Renaissance. During this same period, Snyder and Whalen began going together to the American Academy of Asian Studies (now the California Institute of Integral Studies), where they heard and met Alan Watts, and later also D. T. Suzuki. From among the audiences there, they got to know Claude (Ananda) Dahlenberg, who cofounded the East-West House and later became an ordained Zen priest under Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. And from connections there, they began attending the regular Friday evening literary gatherings held at his home by the poet Kenneth Rexroth.

Other Friday evenings found Whalen and Snyder in Berkeley for the study group with Rev. Kanmo Imamura and Jane Imamura at the Berkeley Buddhist Temple. Together the Imamuras were descended from the most important old families of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, yet they welcomed the young men, going so far in the subsequent years as to turn their little church publication—the Berkeley Bussei—over to the artist Will Petersen for a time. Snyder, Whalen, Ginsberg, and Kerouac all published early poems in its pages. The benevolent Imamura family gave both Snyder and Whalen their first contact with people actually practicing Buddhism instead of purely discussing its philosophies and traditions.

Whalen might have made his way out to the Academy or over to the study group without Snyder’s impetus, but Philip was much given, even then, to the sedentary life. As long as he could, he spent hours each day reading, writing, drawing, playing music, doodling, staring into space—wondering from time to time where and how he could find a job that wouldn’t drive him crazy. He ventured out when he needed to—for cigarettes or food or for fresh air—but he had nothing like the get-up-and-go Gary had. It is, in fact, difficult to think of anyone with the drive and sense of adventure the young Snyder had. These qualities propelled him up mountains, up trees, down the hole of tankers, out into deserts, back into libraries, into universities, into monasteries, across the country, out of the country, across oceans; they armored him against the many outer and inner obstacles an un-moneyed young man might encounter in such travels; they sustained him as he went where he needed to go, saw what he wanted to see, studied what, and with whom, he needed to study, worked as he had to, and cut loose when he could.

Whalen certainly profited directly from Snyder’s enormous, disciplined energy. Gary’s confident style also worked as a magnet: Kerouac was magnetized, for example, as were a steady stream of young women. The shy, socially awkward Whalen profited from this as well, in the sense that it afforded him more contact with females and feminine energy than he otherwise would have been able to arrange for himself. Falling in and out of love—these essential emotional territories for a young poet were much more accessible to Philip because of women who were initially attracted to Gary. Signal among such introductions and completely transcending any other was the introduction Gary made between Joanne Kyger—his future wife—and Philip in 1958. Philip fell helplessly in love with Joanne, and stayed that way for his remaining 42 years. Gary observed Philip’s crush on Joanne, possibly underestimated its profundity, but correctly gauged that it presented no threat to his own relationship with her. Joanne went off to Japan and a swift marriage with Gary. Philip stayed home, haunted.

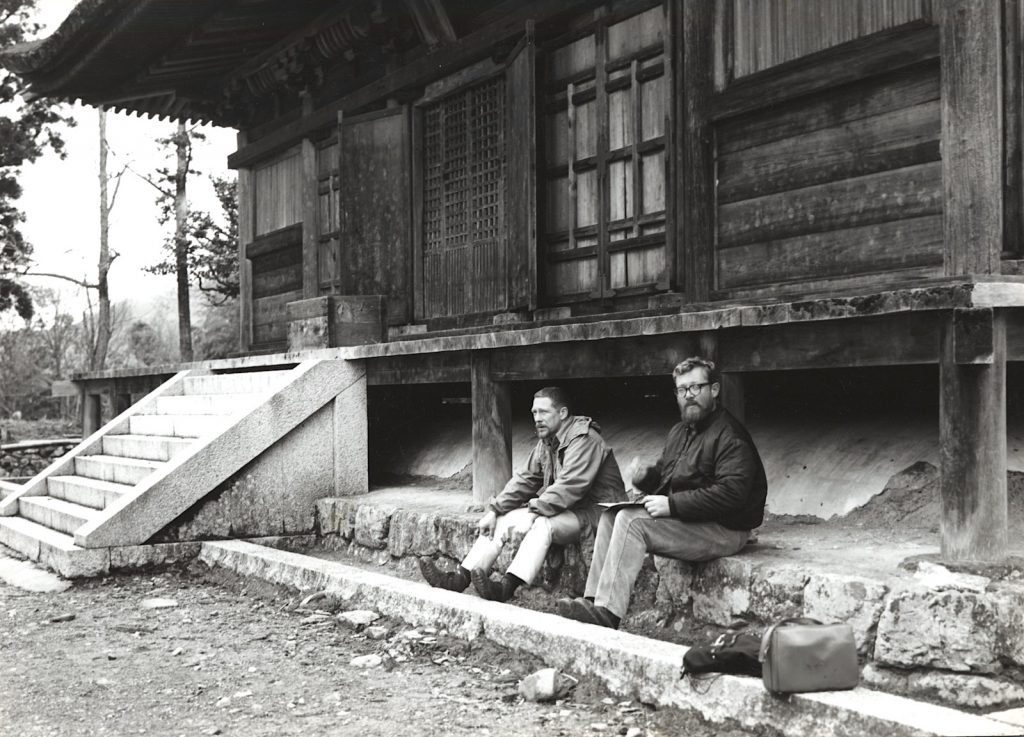

Philip’s own two sojourns in Japan—so crucial to his writing and his Buddhism—came about through Gary’s agency. Knowing Philip in 1965 to be impoverished, functionally homeless, unhealthy, and depressed, Gary arranged a teaching job for him in Kyoto, instructed him in all he would need to know to negotiate visas and transportation, and gave him a place to live for several months.

By 1971, both men back in California, the obvious outer good turns Gary had given Philip’s life ceased to be so necessary, to occur so frequently, or to be so easy to trace. With Philip soon settled in San Francisco Zen Center’s housing, and Gary getting phone service in his Sierra Nevada home, their letters to one another tapered off. Such hard evidence as does remain shows no lessening of affection, no diminishment of respect between them. They were simply absorbed in the demands of their parallel lives: Gary with raising a family, working with a zendo, publishing continuously, and teaching at UC Davis; Philip, roughly 150 miles to the west, with the people and the routines of the San Francisco Zen Center. He spent the days educating himself and students about Zen history, and in working with and for his teacher, Richard Baker Roshi.

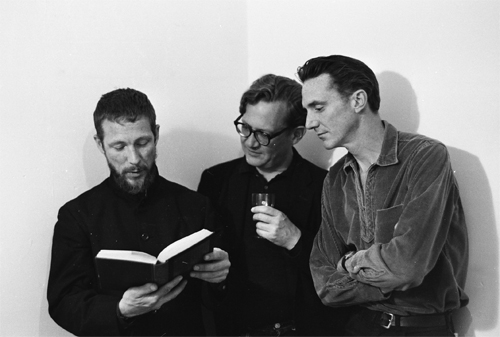

Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and Lew Welch before a poetry reading at Longshoreman’s Hall, Photograph by Jim HatchThe last big service Gary offered was to help officiate, together with Zen teachers Baker Roshi and Norman Fischer and poet Michael McClure, Philip’s funeral service at Green Gulch Farm Zen Center in September 2002. Relaxing Japanese ceremonial rigor by a hair, these four conducted a memorial both traditional and warm. Flashes of humor took place; tears flowed. Gary dressed for the role, looking exactly who he was: an outdoorsman wearing with craggy elegance, a dark suit, white shirt and tie, his dignity and city clothes conveying deep respect. After Baker Roshi’s opening rituals and remarks, Gary spoke. Hebowed crisply to the shrine with Philip’s ashes upon it, and still facing it, told him, “Hey buddy, I’m going to say some words about you.” Snyder then turned to the audience and read slowly from prepared remarks—an essay he’d titled “Highest and Driest: For Philip Zenshin’s Poetic Drama/Dharma.”

In this trenchant eulogy, it is possible to see some of the other side of the friendship. For a creative friendship to last more than a half-century, for it to remain loving and humorous and bright at whatever remove, both parties have to be getting something. For the friendship to allow a living man to address, with utter naturalness, a box of his dead friend’s ashes saying, “Hey buddy,” the path between their hearts has to be a well-traveled, two-way route.

Being part of Phil’s circle [at Reed College] was like being in an additional class—having an extra (intimately friendly) instructor, one with nutty humor and more frankly expressed opinions. He extended us into areas not much handled by the college classes of those days, such as Indian and Chinese philosophy….Philip led the way in making conversation possible, and then making poetry out of the territory of those readings.

Seven years his senior, Whalen was, when they met, more accomplished than Snyder in almost every academic field. Through industry and native intelligence, Gary made huge strides in learning, catching up to and—in Asian studies and languages certainly—surpassing his older friend. Still he maintained a deferential tone: “Cher Maître” was not an uncommon opening for a letter from Gary to Phil, even if the respect in it is coated with dollop of fun. In Philip he found someone older, familiar, strange, and friendly who’d been studying classics of all kinds for much longer than he had, and who was undeniably already a poet. More explicitly, Snyder states: “He first showed me the difference between talking about literature and doing it, and pointed the way in Asian philosophy and art.” Since Gary Snyder spent most of the rest of his life “doing” literature, most of it profoundly affected by Asian philosophy and art, this is no small responsibility to lay at Whalen’s feet. If this seems an exaggeration of Whalen’s importance, and it does feel bold even to suggest it, then consider that these words come from the author’s introductory note to The Gary Snyder Reader, a 600- page summary volume assembled after more than 45 years of publishing poetry, prose, and translations. The whole big, fat, rich book— the essential texts from a life’s writing—is also dedicated to Whalen. “For Philip Zenshin Whalen,” it begins. Snyder adds the opening lines from Confucius’s Lun Yü, as an epigraph;

K’ung said:

To learn and then put it in practice—isn’t that a delight?

To have friends come from afar—isn’t that a joy?

Both in his eulogy for Philip and his author’s note dedicating The Gary Snyder Reader to him, Snyder uses Whalen’s Buddhist name, calling him Philip Zenshin Whalen. For Gary, as for Philip, names and naming held real significance, so that by including Whalen’s Zen name, Gary was pointing to more than Philip’s literary endeavor. A different man answered to “Zenshin Ryufu” than to “Phil,” “Philip,” “Philip Glenn Whalen,” or “old buddy.” Philip felt, as the ceremony insists a postulant should feel, that his priest’s ordination cut him away from previous history and gave him a new start in life. Together with the new name, ordainees received new robes, new eating bowls, new or renewed vows, and new family ancestors, a lineage. Buddhism is associated with rebirth, but the ceremony that left Whalen a priest is called tokudo—which translates as “home departure”— emphasizing its disentangling effects. A person emerging from tokudo is known as an unsui: not monk, not priest, but “cloud-water person,” one who should henceforth float, constantly changing like a cloud, and reflect, like clear water. In actual practice, one still drags around a good deal of baggage, and the unsui’s new role as “a child of the buddhas” brings with it binding specificity with regard to deportment. It may be an awakened family he or she has just joined, but an unsui is still subject to family dynamics. The path forward consists in balancing the liberating and binding aspects of the new role, and in unpacking, sorting, and using or discarding the contents of the luggage. Snyder knew this well, having gone through tokudo himself in Japan in 1956. When he dedicated his big collection of writing to Philip, it was to the man doing just this work. When he eulogized his old college pal, it was a eulogy for an unsui.

Discriminating Snyder’s words this way would be unfaithful to their sense if they were not reintegrated, for Gary did not see Philip’s Buddhism as separate from his poetry, or his life generally. These were not conflicting parts of Philip; they had been braided together.

Once a priest, it was clear that this was Philip’s true vocation. He had the dignity, the learning, the spiritual penetration, and the playfulness of an archetypal Man of the Cloth, of any tradition, and yet was not in the least tempted by hierarchy or power. Philip never left his poetry, his wit, or his critical intelligence behind; his way of poetry is a main part of his teaching. His quirks became his pointers, and his frailties his teaching method. Philip was always the purest, the highest, the most dry, and oddly cosmic, of the Dharma poets we’ve known—we are all greatly karmically lucky to have known him.

Gary went to a Japanese monastery years before the idea even occurred to Whalen to do so. He learned the people and places of Zen years before Whalen set forth to the old country; Gary developed a meditation habit before Philip did, and he led Philip into Zen’s literature. Nevertheless, Gary appeared to harbor a feeling about him, as all Whalen’s close friends did, that whether or not he had gone through the ceremonies, whether or not he wore the robes, there stood in Philip Whalen a spiritual man. Gary confirmed this one evening at a dinner with some poets and other friends. Overhearing a remark addressed to the Chinese poet Bei Dao about how Whalen was a sort of brother figure, a literary sibling for Snyder, Gary nodded, “Older brother. And also kalyanamitra. Philip was my good spiritual friend, my kalyanamitra.”

The author’s introduction to The Gary Snyder Reader concludes: “And finally nine bows to Philip Zenshin Whalen, retired Abbot of the Hartford Street Zen Center in San Francisco. Phil has been a friend and mentor since undergraduate days….Later we both came to Zen meditation. Over the years we’ve shared bare-floor flats in Portland, Berkeley, and San Francisco, tight quarters in Kyoto, plus some huge and funny spaces of the mind.”

Philip and Gary shared Zen mind, meditation mind. This is not a personal possession, and such a space of mind belongs to everyone, consciously or unconsciously. Whalen and Snyder actually meditated together, sitting next to one another; they shared the basic method of accessing Zen mind. They shared as well an influential respect for the lineage that had delivered to the present day this method, the lineage that pointed out Zen mind and trained it. This is to say that they shared the practice of Zen, which to most of its disciples does not feel like the complete realization of buddha mind, but which—according to not a few accomplished teachers—is exactly identical with it. Thus they shared buddha mind. They knew this.

Oddly, given their very different styles—Snyder energetic, peripatetic, strict; Whalen still, slow, indulgent—they shared a taste for discipline and repetition. For many decades both men simply rolled over the resistance to getting out of bed in the early dark for meditation. They trampled as well on the pesky resistance to going back into the meditation hall of a sultry afternoon, during extended practice sessions. Quite apart from the semimagical (but true) explanation that one’s ego is threatened by meditation and therefore puts up resistance to doing it, there is the feeling, known to all who try it, that one does not meditate very well. The actual experience of it does not compare well to one’s imagination of what meditation is supposed to be, nor to descriptions—meant to be supportive—that one might read in a book. One feels a failure at it, and who needs more failure? To continue for years to practice, and to glean the undeniable benefits of meditation—among them mindfulness, empathy, selfknowledge, insight, flexibility, and humility, as well as the occasional entrance into refined absorptions—one needs to come to terms with the feeling of failing. In Japan on New Year’s Day of 1967, Philip got most of a poem out of the insight that the feeling of failing simply belongs to the life of a practitioner (of any serious discipline) and that whatever one did to avoid it was simply delay or detour. He develops the insight in typically cuckoo fashion:

FAILING

The practice of piety. The practice of music. The practice of calligraphy. These are exemplary pastimes. The practice of rereading the novels of Jane Austen. The practice of cookery. The practice of drinking coffee. The habit of worrying and of having other strong feelings about money. All these are vices. We must try not to write nonsense, our eyes will fall out.

In answer to all this my head falls off and rolls all messy and smeary across the floor K E E P T A L K I N G squelch slop ooze.

Philip and Gary knew early on that being poets meant an active engagement with poetical elders. They understood the power and function of lineage from the Zen context; and even if one wrote one’s poems alone, they saw with increasing clarity that poetry too had lineages. In the spring of 1955, Philip and Gary were absorbing what they could from these poetical lineages, but at the same time were trying to find ways to distinguish themselves from them. Particularly they wanted a way out from under the heavy influences of their immediate forbears, including Pound, Eliot, Stein, Joyce, Williams, Jeffers, and Stevens. “You felt everything had already been said. It had all been done,” Whalen told a Naropa University class, adding that the poetry scene had also come under the fairly tight control of university academics.

In D. T. Suzuki’s martial language describing Zen training, they’d read of “dharma combat”—spiritual life-and-death-style encounters with the master—and they understood that this kind of differentiation from the previous generation can only take place in an atmosphere of mutual respect. Forms to ensure this respect are built into Zen ritual. Not so in the poetry world. The tricky balance of gratitude and arrogance and irritation and pride one felt toward one’s lineage needed to be worked out for oneself. With one of the giants, however, this was straightforward.

William Carlos Williams had shown Snyder and Whalen only kindness during his 1950 visit to Reed College. He’d spent social time with them, read and critiqued their work and pushed them onward as poets. Thus when Dr. Williams—weakened by two serious strokes and a hospital stay —came west in 1955 for a reading tour, they made sure to see him. Philip approached the great poet after his reading at the University of Seattle on May 16 and reported to Gary that Williams had been “most friendly and gracious.” That Philip regarded Williams as a father and that he’d been thrilled when the old man had remembered him, Philip only admitted in a poem eight years later, upon the occasion of Williams’s death. In a letter to Snyder, Philip merely said that while Williams seemed “much enfeebled,” he found him mentally and poetically sound.

Gary too thought Williams “did well” when he read some weeks later, despite technical ineptitude on the part of the University of California at Berkeley sound department, which Gary described by saying, “the fucking school tried to ruin his talk.” In fact, the clownish behavior of the aides so irked Snyder that he devoted a long paragraph to it, concluding, “Jesus I was mad, I practically got up and beat the shit out of those English department snots that did it to him.” Philip sent wishes by return mail that Gary might see Dr. Williams under “some less irritating conditions.” He added that Williams had received strange treatment up in Seattle as well. “He was introduced here by Roethke with a rather florid gesture—‘one who teaches us that a poet must be a man’—and here was a MAN—not a long speech but rather fancy—yet delivered with great passion &c. Rather embarrassing. One expected W in a cod-piece.”

Although the labels comprise dauntingly wide spectrums of meaning, it must be possible to say something like “buddha mind” and “poetry mind.” It is possible to say these things to people who try to practice them. Meditators and poets talk like this all the time; they only rarely force precision on one another, probably because the open meanings make conversation possible and fruitful, and because once definition starts, it takes over. People who try to practice buddha mind and also to write poetry talk like this because there is a rub between these two minds.

RIDICULING LITERATURE

Humans are endowed with the stupidity of horses and cattle.

Poetry was originally a work out of hell.

Self-pride, false pride, suffering from the passions—

We must sigh for those taking this path

to intimacy with demons.

That’s Zen master Ikkyu, himself a fine and famous poet, writing in 15th-century Japan. That’s also Gary Snyder, using Ikkyu’s poem (and later giving a commentary on it) at a conference he organized with Zen abbot and poet Norman Fischer in 1987 to discuss “The Poetics of Emptiness.” The record includes preliminary written statements, circulated before the conference, followed by transcripts of at least three panel sessions. The conference participants meditated together, ate together, and heard Zen talks together. Discussion groups, formal and informal, took place. Philip wrote in his statement that he had developed both a writing habit—explicitly comparing it to a drug habit—and a meditation habit. “In my experience, these two habits are at once mutually destructive and yet very similar in kind. I write for the excitement of doing it. I don’t think of an audience; I think of the words that I’m using, trying to select the right ones. In zazen I sit to satisfy my meditation habit. It does no more than that. But while sitting I don’t grab onto ideas of memories or verbal phrases. I simply ‘watch’ them all go by. They don’t get written.”

Snyder wrote, “When I practice zazen, poetry never occurs to me, I just do zazen. Yet one cannot deny the connection.”

Whalen said, “I became a poet by accident. I never intended to be a poet. I still don’t know what it’s all about.”

Snyder said, “I have to confess that like Phil, I don’t have the faintest idea what my purpose is or what’s going on, and I never have. I became comfortable with that mystery a long time ago—that I would never know how any of these things fit together in any explicit way.” In subsequent panels, however, Snyder offered several brilliant—if somewhat contradictory—theories of “how these things fit together.” Whalen didn’t say much more on the topic. He declined to even attend the final panel.

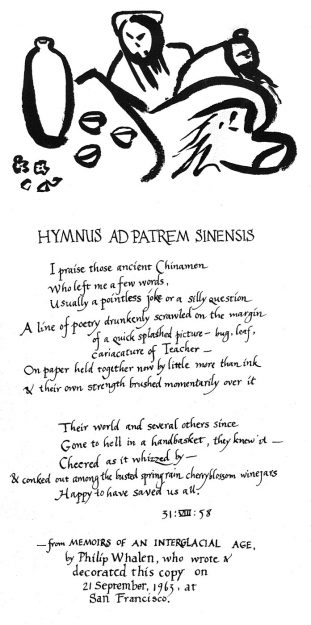

In the undefined, sometimes uncomfortable edges between the meditator’s mind and the poet’s mind, Snyder and Whalen availed themselves of classical solutions. One of these, brought forward at the conference by both Anne Waldman and Andrew Schelling, is devotional verse: praise and offering to higher powers— to wisdom itself, to ethereal as well as earthly embodiments of wisdom, to the lineage of wisdom and to protectors of that lineage. Whalen and Snyder both wrote oblatory poems to the goddess Tara, the national protector of Tibet and one of the rare female figures seen as holding the rank of a buddha. Snyder went so far as to call his monumental poem Mountains and Rivers Without End, an offering to Tara. Both wrote poems in praise of Zen teachers: Snyder’s breakthrough translations of Han Shan and Whalen’s famous “Hymnus ad Patrem Sinensus” are ready examples; there are more. In these works they imported as well the playful, teasing, or even mocking style of Zen. Whalen portrayed his heroes—“ancient Chinamen”—as “conked out among the busted spring rain cherry blossom wine jars. Happy to have saved us all.”

Beyond this, both hewed (Snyder explicitly, Whalen intuitively, especially as time went on) to a Chinese preference for expressing sublime truth through mundane subject matter and plain vocabulary. It was lost on neither Snyder nor Whalen that China’s greatest poets had been Zen monks themselves, or friends with Zen monks, belonging to an elegant circle of spiritual, literary, and calligraphic geniuses. Indeed, the existence of Tang dynasty poets like Wang Wei, Du Fu, Li Po or (from the Song dynasty) Su Shih—as well as the subsequent Japanese writer/practitioners like Sesshu and Basho—had made Zen immediately attractive as a spiritual path to Whalen and Snyder at the outset. When they began, both had been looking for ways to talk about insights, emotional disturbances, concept-melting encounters with landscape, love, literature, and art; and both had been looking for spirituality. In the Chinese and Japanese Zen–style poets, they found perfect models. By the time of the 1987 conference, they’d achieved, in different ways, a level of mastery as poet-meditators, and they recognized this in one another. Snyder told the participants how moved he was to hear Philip—his original model for how to be a poet—talk about teaching meditation. A few years earlier at Naropa University, Whalen and Ginsberg fielded a question from a class they’d lectured— did they have favorite Asian poets? Ginsberg recited from memory some Indian and Arabic verse, and names were batted about, but in the end both admitted that one of their favorite Asian poets was the Zen man Gary Snyder.

♦

NANSEN

I found you on a rainy morning

After a typhoon

In a bamboo grove at Daitoku-ji.

Tiny wet rag with a

Huge voice, you crawled under the fence

To my hand. Left to die.

I carried you home in my raincoat.

“Nansen, cheese!” you’d shout an answer

And come running.

But you never got big,

Bandy-legged bright little dwarf—

Sometimes not eating, often coughing

Mewing bitterly at inner twinge.

Now, thin and older, you won’t eat

But milk and cheese. Sitting on a pole

In the sun. Hardy with resigned

Discontent.

You just weren’t made right. I saved you,

And your three-year life has been full

Of mild, steady pain.

–Gary Snyder

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.