“When there are problems, we must be able to provide help, because the purpose of [the Tibetan Children’s Village] is to serve the Tibetan children,” says Jetsun Pema, younger sister of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, in the opening sequence of Amala. Filmmaker Geleck Palsang’s graceful, succinct documentary about Jetsun Pema’s life and work is currently touring film festivals and will soon be available to wider audiences.

Alternating between historical footage and recent interviews with Jetsun Pema and the children of Tibetan Children’s Village (TCV), the organization serving Tibetan orphaned and refugee children in India that she ran from 1964 to 2006, the film recognizes Jetsun Pema’s decades of work on behalf of the Tibetan people. The message of the documentary is clear: without Jetsun Pema’s remarkable leadership, the Tibetan Children’s Village would not be what it is today.

The majority of the documentary consists of engaging, original interviews with Jetsun Pema’s friends; her older brother Gyalo Thondup; teachers from Tibetan Children’s Village who also grew up there as children; and Jetsun Pema herself. Fascinating details about Jetsun Pema’s life as the sister of the Dalai Lama abound. As the first sibling in the family born after her brother was enthroned in the Potala Palace, Jetsun Pema was also the first child whom the Dalai Lama named, following the Tibetan tradition where parents request a lama choose the name for their child. His Holiness was 6 years old at the time. He later personally guided his sister’s education: after she graduated from Catholic boarding school in India, having been described as a “sober” young woman by her friends, she went to study in Switzerland on His Holiness’s specific advice. He told her that she would be better able to serve the Tibetan community if she had additional education. In 1964, he gave her the special task of directing the Tibetan Children’s Village.

In the process of depicting the personal trajectory of Jetsun Pema’s life, Amala also documents the development of the Tibetan Children’s Village. Beginning as a nursery for orphaned refugee children, it grew over time into a network of schools organized around a unique family model in which groups of 20 to 25 children live in homes cared for by foster parents assigned to each house. The schools became a critical agent of preserving Tibetan language and culture by educating the children in both. Cognizant that the children living in exile have both the opportunity and the responsibility to maintain the language and culture denied to their counterparts in Tibet living under the rule of China, Jetsun Pema personally translated textbooks into Tibetan and eventually helped open the Tibetan Language Institute for higher learning.

The film also captures painful moments in TCV’s history, including early on when the organization lacked the facilities and medical care the children sorely needed. At one point, Jetsun Pema describes the year (1964–65) when 150 children arrived after walking to India from Nepal, all extremely ill. Swiss Red Cross doctors volunteering for TCV did their best, but in one night alone, four children died. In the days that followed, a child died every three to four days because of the lack of adequate medical facilities.

The documentary also covers Jetsun Pema’s leadership of the third fact-finding delegation to Tibet in 1980 that revealed horrific abuses of the Tibetan people by the Chinese government. “We spent 105 days in Tibet, over three months, and during all that time, I shed buckets and buckets of tears,” she says in the film. Personal tragedies, such as the death of Jetsun Pema’s husband and one of her daughters, are mentioned too, but only briefly. What is notable, however, in the representation of these personal losses, is that friends recount that even after the death of her husband, when her children were still young, and after the death of her daughter, she did not let her pain affect her work.

Overall, Geleck Palsang balances heartbreaking moments with interviews by TCV graduates and teachers as they describe what the school has meant to them. A particularly moving and heart-lifting scene shows TCV alumni gathering to formally honor Jetsun Pema, and weeping as they sing to her and pray for her long life.

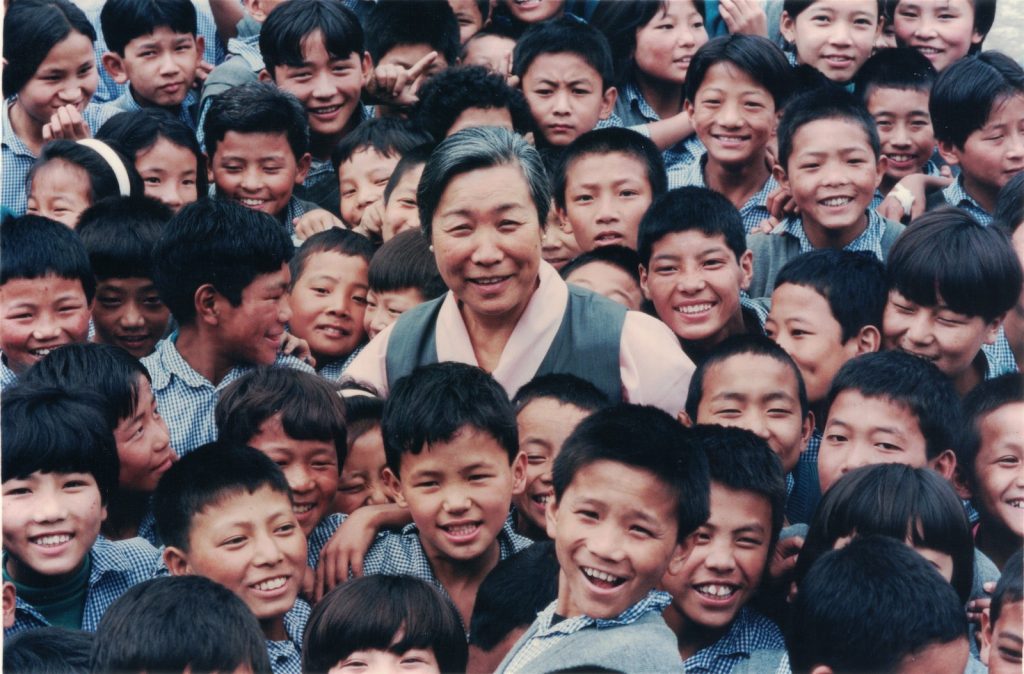

It’s no wonder that she is known as Amala, or “mother,” to the thousands of children who grew up at TCV. Indeed, Jetsun Pema’s own daughter says that her mother was equally mother to all of the children there as much as her own.

By celebrating Jetsun Pema in this documentary, Geleck Palsang honors both the accomplishments of an intrepid and resourceful leader, and the contribution of the Tibetan Children’s Village itself. Not only has the center provided a safe and loving home and education for thousands of Tibetan children over decades, but it has also helped preserve Tibetan language and culture for current and future generations. While viewers may leave wanting to know even more about Jetsun Pema’s personal story and fascinating life, it is likely that this film features her just as she would prefer: as a dedicated servant for the Tibetan people and the preservation of their unique culture in the face of a challenging and increasingly integrated world.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.