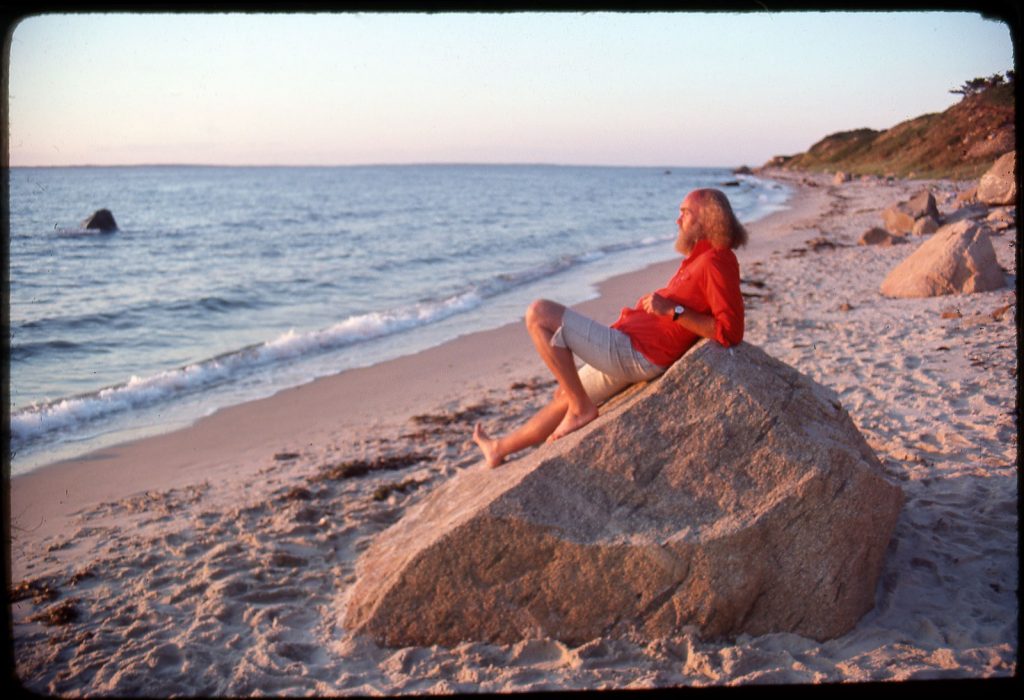

Over the course of a nine-decade cultural mash-up, Ram Dass morphed from a member of Boston’s upper-class nobility named Richard Alpert into one of the world’s most iconic and widely read spiritual teachers.

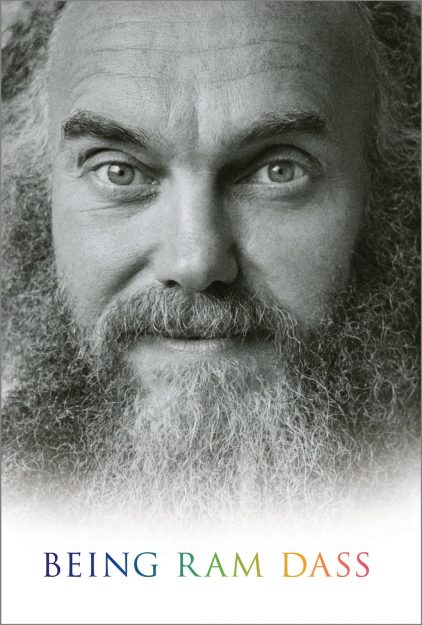

Being Ram Dass, published posthumously in January 2021, is his 17th and final book.

Being Ram Dass

by Ram Dass with Rameshwar Das

Sounds True, January 2021,

$29.99, 496 pp., cloth

His breakthrough title, Be Here Now, was written a half-century ago and has sold over 2 million copies. The counterculture work resonated with young people experimenting with a lifestyle inspired by Ram Dass and his partner in crime, psychedelia, and academia, Timothy Leary. From the ivy-covered towers of the Harvard Psychedelic Project, Leary admonished “Turn on, Tune In, and Drop out,” inspiring bands of young seekers to throw down limits and live life on its own terms. Richard Alpert joined the colorfully clad current; he hit the road on a spiritual search and ended up in the foothills of the Himalayas where he met his Hindu guru Neem Karoli Baba who bestowed upon him the new moniker Ram Dass—“servant of God.”

When Ram Dass died in 2019, there were few stories about his vast and fascinating life that had not been told . . . and told . . . and told.

Readers knew about Harvard and India as well as his encounters with Aldous Huxley, Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, Allen Ginsberg. They knew he liked to drive powerful sports cars and fly his Cessna through mountain passes. Moviegoers had seen the documentaries about him and heard him speak about living in the soul rather than the ego, the heart rather than the mind. Fans held their breath, prayed, and followed his arduous journey back from a devastating stroke in 1997, which left him with aphasia and the right side of his body permanently paralyzed.

In 2013, I did a private retreat with Ram Dass at his lush compound in Maui, which I wrote about for Tricycle. In a sidebar published with the article, I reviewed his book Polishing the Mirror, which had just come out. The book, he explains, is about the “process of witnessing . . . our own actions, thoughts, and emotions with an attitude of tolerance and love.”

But I was disappointed the book wasn’t more personal, focused on aging and dying in light of his age and his disastrous stroke. Did he have another book in him, I wondered?

Indeed he did. Walking Each Other Home, Conversations on Loving and Dying (2018) was a thoughtful reflection written with dharma sister Mirabai Bush, part of that original satsang, or spiritual community, who hung at the foot of Neem Karoli Baba’s wooden palette decades ago.

And this final book, Being Ram Dass, is the icing on the Ram Dass oeuvre. It is almost 500 pages of biography with all the details fleshed out and colored in. Over the past decade, satsang-buddy Rameshwar Das traveled to Maui three or four times a year and holed up with Ram Dass in his suite overlooking the Pacific. Sometimes joined by Dassima, Ram Dass’s confidante and manager and literal right side of his body, they pulled memories from archives and their minds, bringing back old friends nearly forgotten and recalling places last trodden ages ago. As the sun set or rainbows criss-crossed or the Traveler Palms smashed against each other in the torrential rains, Ram Dass would detail his struggles with his family of origin, the days with Leary, how he grappled with self-identity and sexuality, how he discovered at 70 he had a son. The cast of characters is a Who’s Who of 20th-century spiritual masters from Muktananda and Chogyam Trungpa to Jack Kornfield and Roshi Joan Halifax.

What Being Ram Dass does so skillfully is consolidate all the stories in one place and elaborate on them. By painting such a precise picture of their time together at Harvard, Millbrook, and in Mexico, one understands why Leary, while dying, was insistent that Ram Dass accompany him on his slip slide to the other side. After really getting to know the Alpert family you understand why Ram Dass used to joke: “If you think you’re enlightened go spend a weekend with your family.”

I would have preferred more about Ram Dass’s final chapter amongst the magical Maui ménage, doted upon by the “super monkeys,” as he called his young, strong caregivers, evoking Hanuman, the servant of God in monkey form. I wanted to be part of the conversations between Ram Dass and Wayne Dyer, his neighbor, or Jack Kornfield, who visited often with his wife, dharma teacher, Trudy Goodman. I want to hear Dassima’s stories.

Who knows? Maybe there’s one more book about Ram Dass.

♦

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.