While there is no shortage of serene and benevolent buddhas, Buddhist folklore abounds with hell-raising zombies, vampires, ghouls, and ogres. But they’re not just the stuff of myth and legends. Depending on whom you ask, these ferocious monsters are thought to be as real as you or me, or serve as potent symbols of our less enlightened sides.

Since reincarnation sits at the heart of Buddhist cosmology, we are never far from becoming the monsters we fear. In tantric traditions, practitioners are taught that subjugating outer demons is really about taming inner ones. As you reflect on the creatures rounded up in this cross-cultural compendium, you’ll see that monsters do more than scare people into acting more virtuously. They also clue us in to the monsters within us, the most destructive and flawed parts of ourselves. Their role is not to harm, but to show us that our form is always changing from demon to bodhisattva and back again.

Pretas: Ghosts Who Just Can’t Get Enough

Many Buddhist monasteries have a wheel at their entrances that is inscribed with the six realms of worldly existence. The realms depicted in the Wheel of Life—a graphic illustration of core Buddhist teachings and cosmology—are inhabited by gods, demigods, animals, humans, pretas (or hungry ghosts), and hell beings.

Pretas have bloated bellies, pinhole mouths, and constricted throats that signify their insatiable hunger and thirst. Taken literally, they are what awaits us in the next life if we give in to our greed, but they also serve as a metaphor for the grasping state of mind that leads to dissatisfaction, (a state we’re all familiar with). They are compulsive spirits prone to addiction, and according to Hindu mythology, where pretas first appeared, there are over 35 colorful types who live on the brink of insanity.

While they are popularly referred to as hungry ghosts, the term preta in Sanskrit directly translates as “departed” or “deceased,” indicating that these frightful apparitions are really spirits of the dead who did not receive proper goodbyes from their families and are thus condemned to starvation.

In Japanese Buddhist demonology, they are known as jikininki, or human-eating ghosts. Born of a miserly and self-serving mind, these nocturnal demons are said to live on the outskirts of villages, near cemeteries, scavenging for fresh corpses. Their appetite for rotting human flesh and feces, however, is not their most terrifying attribute; the jikininki possess the supernatural ability to camouflage as humans by day and often go unnoticed.

To ward off these creatures that roam in our midst and in our minds, Japanese monks and nuns hold a segaki ceremony, during which they feed the ghosts. This festival has traveled far from Japan’s monastic circles. Today it is celebrated every trick-or-treat season at the Dharma Rain Zen Center in Oregon, where Portlandians get together to offer remembrance prayers to those who have died and cleanse their own unresolved karma.

Narakas: Welcome to Hell

Next door on the Wheel of Life are narakas, or hell beings, which tend to get less attention than the hungry ghosts despite being even more spine-chilling. Known for their hot tempers, these tormented denizens of hell are marked by unchecked anger and aggression.

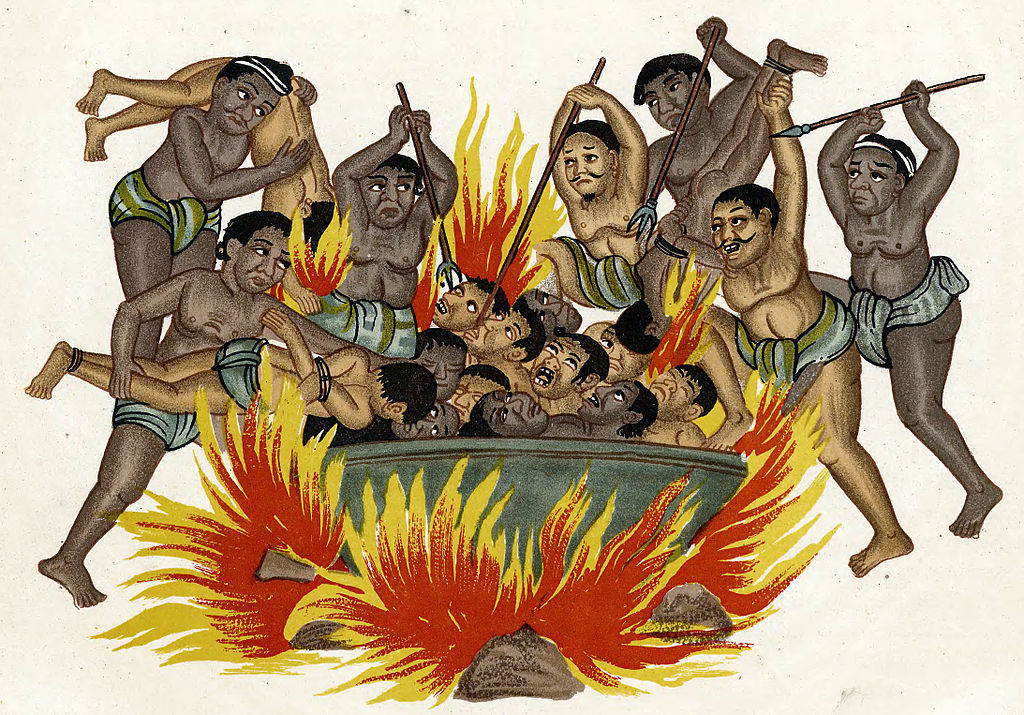

Actions motivated by hatred will land you a one-way ticket to one of several hundred hells and sub-hells found in Naraka, the Buddhist underworld. Described in considerable detail in the Devaduta Sutta, narakas pay their karmic debts in hot hells, where they are impaled by blazing iron tridents, dismembered by axes, boiled in cauldrons, or burned with fire by the henchmen of Yama, the Lord of Death. The cold hells—frozen, desolate plains without a sun or moon—are no picnic, either. In this icy purgatory, the skin of unfortunate victims splits like lotus flowers and bursts with blisters.

As soon as these beings are crushed to death or perish from exposure, “they come back to life,” writes Tibetan master Patrul Rinpoche (1808–1887) in The Words of My Perfect Teacher, “only to suffer the same torments over and over again.” Much like the feeling of hate, the pain inflicted here loops around on itself. But this torture, like everything else, eventually ends—although it could last millions of years.

Throughout East Asia, Buddhists perform devotional practices to invoke Ksitigarbha, the bodhisattva who airlifts beings from the hells to higher ground. Counted among the eight “heart sons” of Shakyamuni Buddha, this revered Mahayana deity is usually depicted as a simple monk. Those who find themselves overcome by self-destructive thoughts or awash with anger can call for Ksitigarbha’s swift rescue by reciting his effective mantra: Om ah Kshiti Garbha thaleng hum.

Delogs: Tibetan Zombies Who Aren’t So Mindless

Hell beings are not the only creatures to tour the dark side of the Buddhist cosmos. In Tibet, there is an entire genre of biographical literature written by and about delogs, men and women who die, travel to the lower hells, and then return to the human realm to recount their tales. These born-again Buddhists warn the living about the terrifying fates that await them if they misbehave.

In her firsthand account, Journey to Realms Beyond Death, Dawa Drolma shares her experience of entering a death-like meditative state back when she was a teenager. For five days, the 16-year-old lay cold and breathless while her consciousness moved freely through other realms. Escorted by the wisdom goddess White Tara, Dawa Drolma reports meeting deceased family members, high lamas, bodhisattvas in the heavens, and tortured spirits in the hells. As was the case with this 20th-century boundary-crosser, many delogs go on to become great advocates and propagators of the dharma.

Tengu: Mischievous Demon Crows

Bad karma can turn even monks into vengeful demons. In medieval Japan, insincere Buddhist monks ran a high risk of being reborn as tengu. Equal parts man and crow, tengu are imaginative, exploitative, and not without a perverse sense of humor. The mischief-makers are fond of harassing monks meditating in the mountains, causing rock slides, knocking over buildings, cutting down trees, and setting forests afire. Tengu are also deft martial artists and have the power to possess people. To outsmart a tengu, you’ll have to cater to their sweet tooth. Rumor has it that they like bean paste and rice.

Kishimojin: The Reformed Baby Eater

The child-eating-demoness-turned-goddess Kishimojin exemplifies how no Buddhist monster is beyond redemption. Kishimojin (who goes by the name Hariti in Nepal) is an especially important figure in contemporary Nichiren and Shingon schools. During her days as a demon, Kishimojin abducted and killed children in order to feed her own brood, which numbered into the thousands by some accounts.

To convey the pain that she was causing other mothers, legend holds that Shakyamuni Buddha hid the youngest of her children in his alms bowl. The distraught matriarch begged Shakyamuni to return her son, promising that she would never kill another child and would adopt the Buddha’s teachings. Suitably chastened, the new Buddhist convert became a guardian deity and vowed to safeguard children and women in childbirth.

Belu: Cannibalistic Ogres with a Soft Side

Hailing from Myanmar, belu, a species of ogre, are particularly difficult to detect. They look exactly like humans, save for their blood-red eyes and inability to cast shadows. With sharp fangs and a corrosive touch, these vampiric demons are skilled predators; few victims have been known to escape their attacks. (If you’re feeling adventurous, venture to Myanmar’s Bilu Kyun, or “Ogre Island,” for a possible sighting.)

Belu may be cannibals, but they’re not all bad. There is a benevolent faction, the panswe belu, who despite their curved fangs are herbivores and subsist on flowers and fruits. Popa Medaw, the “Mother of Popa,” is perhaps the most famous flower-eating ogress in Myanmar. This powerful Burmese nat [local spirit], as her title suggests, has dominion over the extinct volcano Mount Popa and assists devotees in all religious endeavors, including the construction of pagodas.

Every August, tens of thousands of visitors flock to a village north of Mandalay, where a week-long nat festival is held to pay homage to Popa Medaw’s two rebel sons, the Taungbyon brothers. In the 11th century, the influential duo was enlisted by King Anawrahta—who established Theravada Buddhism as the country’s national religion—to secure a tooth relic of the Buddha from China. Although their mission was successful, the monarch later ordered the brothers to be executed because they were more interested in playing marbles than building a temple. (Gross and disturbing fact: the brothers were killed by having their testicles crushed.) The pagoda was eventually finished and is a major tourist attraction and pilgrimage site.

Nang Ta-khian: Thailand’s Seductive Tree Spirits

The righteous need not be afraid when wandering through Thai forests. Those who have transgressed, however, will incur the wrath of otherwise benign female tree spirits called Nang Ta-khian. Often heard wailing in the night, these woodland protectors reside in the body of Ta-khian trees (Hopea odorata), an endangered species valued for its wood, and can shift at will into beautiful, seductive young women. To avoid their fury, worshipers place traditional Thai silk dresses at the base of their trees.

That said, you better think twice before you go tree-hugging or felling in Thailand. Nang Ta-khian are sacred sirens of the woods, and those who get too close may not make it out alive.

♦

As threatening as these flesh-eating ghouls and demons may be, the most frightening fact of all is how easily we can turn into monsters ourselves in this life or the next. Luckily, the story goes the other way, too, with the possibility of redemption never too far away. But if you want a real scare this Halloween, take a long look inside your own mind.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.