After the Buddha’s enlightenment, his aunt and adoptive mother, Mahapajapati Gotami, asks him to ordain women and welcome them into his new monastic community. The Buddha declines to fulfill her request. But Mahapajapati Gotami doesn’t give up—accompanied by a large gathering of women, she sets out to ask him again.

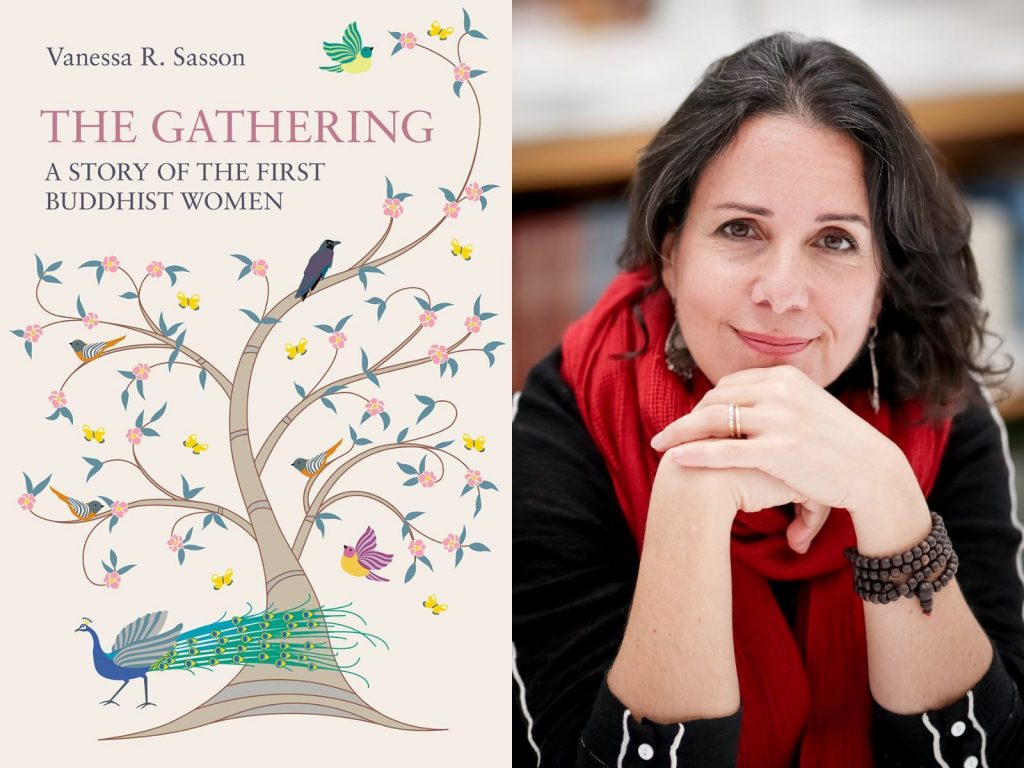

In her new novel, The Gathering: A Story of the First Buddhist Women, scholar Vanessa R. Sasson offers an imaginative retelling of the women’s request for ordination, following the women as they travel through the forest together seeking full access to the Buddha’s teachings. Building on decades of research and drawing from the poems of the Therigatha, the novel explores how the women navigate the paradox of seeking ultimate liberation while still bound by social inequality.

In a recent episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, spoke with Sasson about what we can learn from the first Buddhist women’s resilience, how contemporary women monastics understand this story, and the role of mythology and storytelling in the Buddhist world. Read an excerpt from their conversation below, and then listen to the full episode.

You explore the many different types of freedom that the women are seeking in making the journey to ordain: freedom from hierarchy, from familial bonds, from guilt, and from shame. Can you say more about these different motivations? Well, this is what’s so beautiful about the literature, and I think all of this is reflected like a mirror into the present moment because we see the same thing today. In what the literature tells us about these women, they don’t all have pure spiritual motivations. They get idealized by the tradition as time goes on, and they become these perfected characters of the Buddhist imagination. But when you look at the Therigatha and its commentaries, you see that so many of these women join what I call the Gathering not necessarily because they want spiritual freedom. Some do. Mahapajapati Gotami, for instance, is the embodiment of that spiritual ideal. But then you have Chanda, who is a homeless widow by the side of the road. She sees the women walking past her, and she says, “If I go with you, will you feed me?” The women say yes, and she says, “OK, I’m coming.”

It’s not always the loftiest of ideals. Some women are escaping brothels, and some women are escaping courtesan houses and bad husbands. There’s one character in the Therigatha who puts a noose around her neck, and just as she’s about to pull it, she hears the Buddha’s teaching and thinks, “Oh, maybe I won’t do this.” And so you have these women who are coming out of all kinds of situations and backgrounds and realities, and they’re not always doing this for some pure intention. They’re doing it because they need a way out. And monastic community can offer that in certain cases.

I think we see this today as well. I don’t know that everyone who becomes a monk or a nun today is always doing it for the highest ideal. Sometimes it’s to get out of their parents’ home or to get out of marriage or to get out of poverty or to get an education. In many ways, it feels like the story is still the same. It’s still hard. Life has not been cleaned up. We haven’t figured everything out. Monastic life is still complicated, and nuns hit walls all the time. [The walls that women face today] are not that different from the walls that we see in the Therigatha that the women are banging up against and trying to figure out how to free themselves from.

The story of the Gathering women also demonstrates how difficult it can be to imagine an alternative when we’re so stuck in our own habits and stories. So how did the women help each other to imagine and actually enact different possible futures? I think the great thing about this story is that the women did it together. What I find so beautiful is that these women couldn’t have done it on their own. Society wouldn’t have allowed them to—the husbands and the temple priests and the brothel owners would have pulled them back. And so the only way they were going to have the strength to pull this off was as a community.

I think this is true so often. When you go to a march, it’s so exciting to be surrounded by other people and to think, “OK, we will do this.” Thinking “I will do this” is very isolating—you’re risking so much, and it’s very hard as an individual to risk so much. But if you’re standing with a group and you do it together, a lot more is possible. And I think that’s what this story tells us.

When the men go [to ask the Buddha to ordain], they go as individuals, one at a time. Sometimes two people will go together, like Sariputta and Mogallana. But most of the men are going by themselves. The women go as a group. And I think that’s what helps them imagine because their world is not giving them much imagination for this. For most women in ancient India, I don’t think that imagination would have been there, that they could be free—that they could do something different and radical with their lives. That’s hard to imagine even today for many of us. And yet when you’re with a group of women who are imagining something together, when you lean on their shoulders and you do it as a group, I think it’s so much more possible then. I think that’s how they did it.

You say that the Gathering women are a community of renunciants who renounced before they even knew if they were allowed. How have you come to understand renunciation in the process of writing this book? I think renunciation is actually really profound, and I think it’s something that I’m learning over time. I don’t think it’s something that you learn just once. When I was younger, I thought of renunciation as a very clear binary of either householder or renunciant. But the more time I spend thinking about renunciation, the more nuanced I think it is.

These women are hoping that the Buddha will give them a spiritual home even if they’ve renounced an actual home. I think that paradox is important, and I don’t think it’s a contradiction. I don’t know that renunciation is supposed to be so radically individual that you have to stay in the middle of nowhere with no one supporting you. I think the reason there are monastic sanghas is because you can renounce some things, but you still need to be held. And so I don’t think of renunciation as quite as radical as I understood it in my 20s when I thought of it as a kind of radical departure, where you’re completely on your own and you need no one. I think that even in renunciation, there’s a question of community and companionship and friendship and love and support that I don’t know that we’ve always had the language for in Buddhist studies. These communities were not individuals standing alone. They were standing together.

This excerpt has been edited for length and clarity.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.